Introduction

Spinal insufficiency fractures are a type of fragility fracture that occurs due to low-energy trauma on structurally weakened or poor-quality bone which would not ordinarily result in fracturing (1). This is most commonly due to osteoporosis affecting patients over the age of 50 or younger patients with risk factors (2). Osteoporosis is a global public health problem and recognising and appropriately managing these fractures is critical to preventing complications including progressive frailty, premature mortality, chronic pain and impaired mobility (3, 4) . This article will focus on one of the most common types of Spinal insufficiency fractures: Osteoporosis related vertebral body fracture, whilst discussing in brief some less common causes.

Prevalence and Pathophysiology of spinal insufficiency fractures

Spinal insufficiency fractures, unlike traumatic fractures, occur due to reduced bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration, which impair the bone’s ability to withstand normal stress. As a result, low-level trauma and even everyday activities can lead to fractures in structurally compromised bone, without the need for excessive external force (ii).

Incidence of spinal insufficiency fractures is greater in the over 50s, affecting women more than men (iv).Spinal fractures often occur following low-level trauma (e.g. a fall from standing height or lower) and can be very painful. Frequently, these present as occult fractures with Insidious, progressive pain, often worse on standing and weight-bearing (5). Duration of symptoms varies, and although a single event can be recalled, often patients present with a progressive pain over weeks or months (iv). Notably, 50-70% of are asymptomatic and identified incidentally.

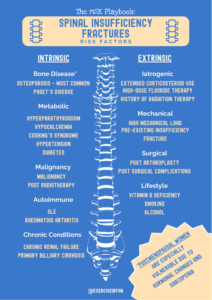

Risk Factors for spinal insufficiency fractures

Osteoporosis is by far the most common cause of abnormal bone health and low bone mass. The causes of abnormal bone quality can be categorised into intrinsic factors and extrinsic factors.

- Intrinsic Factors: These affect bone quality directly due to disease processes, these can be classified further as osteoporosis causing or non-osteoporosis causing

- Osteoporosis is the leading cause due to reduced bone mineral density (BMD). Most patients with spinal insufficiency fractures have osteoporosis on DEXA, with T-scores ≤ -2.5 (6). Several medical conditions contribute to osteoporosis such as

- Auto-immune conditions: Rheumatoid arthritis, SLE

- Chronic conditions: CKD, diabetes, hypertension, and endocrine/metabolic disorders such as Cushing’s syndrome, hyperparathyroidism, Paget’s disease, and renal osteodystrophy (7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14)

- Postmenopausal women are especially vulnerable due to hormonal changes and sarcopenia, which reduces muscle’s shock-absorbing role (15, 16)

- Non-Osteoporosis causing mechanism (usually referred to as ‘pathological fracture’) including metastatic bone disease and osteopetrosis is highly morbid and often causes micro-fractures before overt fractures occur (17) (ii). These are not the focus of this article, but are mentioned here for completion

- Extrinsic Factors: These refer to the effect of external agents on bone health

- Long-term corticosteroid or cancer hormonal therapy

- Radiation, high-dose fluoride therapy, smoking, alcohol, vitamin D deficiency (vii, viii, xv)

- Post-surgical changes (e.g. post-sacroplasty) and pre-existing insufficiency fractures (vii, viii, xv)

Table 1: Risk factors for spinal insufficiency fractures

| Risk Factors | |

| Intrinsic risk factors | Extrinsic risk factors |

| Osteoporosis | Extended corticosteroid use |

| Malignancy | History of radiation therapy |

| Hypertension | high-dose fluoride therapy |

| Diabetes | Smoking / Alcohol |

| Paget’s disease | High Mechanical load |

| Hyperparathyroidism | Post arthroplasty |

| Hypocalcaemia | Vitamin D Deficiency |

| Cushing’s syndrome | Post-surgical complications |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Pre-existing insufficiency fractures |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | Aromatase inhibitors |

| Chronic kidney disease | Anti-epileptics |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | |

Figure 1: Risk factors for spinal insufficiency fractures

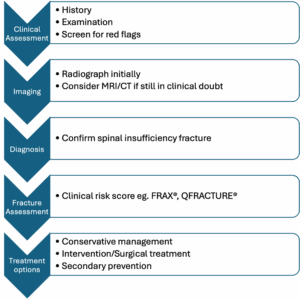

The work up of suspected insufficiency spinal fractures

The flowchart below summarises patient workup and management. Each domain is discussed in detail further below.

Figure 2: Spinal insufficiency fracture work up flowchart

| Category | Details |

| Key Clinical History Questions | • Pain characteristics: onset, duration, site (typically midline), worse with activity, improved by rest • Night pain: common in malignancy or acute fractures • Recent trauma or load-related pain: even minimal trauma may be significant in weakened bone • Unexplained weight loss/night sweats/fatigue: raise concern for malignancy or infection • History of malignancy: particularly breast, prostate, lung, myeloma • Febrile illness or systemic infection symptoms • Neurological symptoms: weakness, numbness, bladder/bowel dysfunction • Frailty or sarcopenia: poor musculoskeletal reserve, increased fracture risk•Age •Previous history of fragility fracture• Parent history of fractured hip • Glucocorticoid use • History of rheumatoid arthritis•Smoking and alcohol consumption |

| Basic Observations & Physical Examination | • Vital signs: temperature, heart rate, blood pressure • Height and weight: compare with previous records • Palpation: midline spinal tenderness, pain on percussion • Spinal alignment: visible scoliosis or kyphosis • Height loss: ≥4 cm can suggest vertebral fracture (18, 19). • Range of motion: reduced flexibility, stiffness • Gait and balance: assess functional impact and compensatory mechanisms |

| Laboratory Investigations | • Myeloma screen: serum protein electrophoresis, free light chains, Bence Jones proteins • Calcium: elevated in malignancy or hyperparathyroidism • Parathyroid hormone (PTH): assess for hyperparathyroidism • Vitamin D: deficiency increases risk of insufficiency fractures • ESR/CRP: raised in infection or malignancy • Renal function: assess creatinine, urea (important for myeloma and calcium balance)• Coeliac serology: tTG-igA, EMA, IgA • Thyroid Function: TSH, T4• FBC, TFT, Testosterone, PSA in men |

| Imaging & Diagnostic Tests | • X-ray: 1st line; useful for monitoring changes; may miss early fractures

• MRI: 2nd line; can usually differentiate marrow oedema secondary to insufficiency fractures from malignancy; guide regarding recency of fracture; more sensitive than CT (xi, 20) |

| Red Flags for Serious Pathology | • History of malignancy or known metastasis • Night pain and unexplained weight loss • Systemic illness: fever, fatigue, raised inflammatory markers • Progressive neurological deficits • Lack of response to conservative treatment (4–6 weeks) • Age >50 with new back pain or history of trauma |

Clinical History

- Often incidental finding in asymptomatic patients

- Presenting symptom is often pain with minimal or no trauma, especially in older adults

- Consider fragility fracture in sudden onset thoracic pain in this age group

- History of previous fragility fractures, smoking, alcohol use, corticosteroid therapy, parental fragility fracture

- Neurological symptoms are uncommon but may include sacral radiculopathy (xi)

- Consider malignancy as a differential; screen for “B” symptoms such as weight loss, fever, night sweats (21, 22)

A note about red flags

- Most red flags commonly used in clinical settings are not strongly supported by evidence for their diagnostic value, with no consensus on which are most useful to identify serious spinal pathology (23, 24, 25)

- When used in isolation, very few red flags provide reliable information (xxiv, 26)

- Despite limitations, red flags remain a key tool to raise suspicion of serious spinal pathology when interpreted alongside patient history and examination (xxiv)

- Clinicians should balance available evidence with patient profile (e.g. age, sex, medical history) to judge how concerned they should be about possible serious spinal pathology (xxiv)

- Emergency/urgent referral pathways should be utilised when serious pathology is suspected (xxiv)

Basic Observations & Physical Examination

- Vitals – Check temperature, HR, BP for signs of infection or systemic illness xxx

- Height & Weight – Compare to previous records; ≥4 cm height loss may indicate vertebral fracture xviii

- Spinal Palpation – Midline tenderness may suggest possible acute fracture (27, 28); osteoporotic fractures can be assessed with closed fist spinal percussion (29)

- Posture – Kyphosis or scoliosis may reflect chronic vertebral deformity secondary to recent or past vertebral insufficiency fractures (xxiii)

- Mobility – Reduced range and stiffness often due to pain or structural issues (xxiii)

- Gait & Balance – Assess for instability, especially in frailty or sarcopenia (30, 31)

Laboratory Investigations

- Myeloma Screen

-

-

- Detects underlying malignancy, a known cause of pathological spinal fractures – Serum Protein Electrophoresis (monoclonal (M) protein/paraprotein), Immunofixation Electrophoresis (e.g. IgG kappa, IgA lambda), Serum Free Light Chain Assay (kappa/lambda ratio), Beta-2 Microglobulin, Lactate Dehydrogenase (32)

-

- Calcium & PTH

-

- Hypercalcemia or elevated PTH may indicate metabolic bone disease (e.g. hyperparathyroidism), which weakens bone and predisposes to insufficiency fractures (33)

- Vitamin D

-

-

- Low levels reduce bone mineralisation and increase fracture risk, especially in older or frail individuals (xxix)

-

- ESR & CRP

-

-

- Elevated levels may signal infection (e.g. spinal osteomyelitis) or malignancy mimicking insufficiency fractures (34)

-

- Renal Function (U&E)

-

-

- Renal impairment can be secondary to myeloma or affect calcium metabolism, both of which impact bone health and fracture risk (xxviii)

-

- Coeliac Serology (tTG-igA, EMA, IgA)

-

-

- Coeliac disease is associated with secondary osteoporosis due to chronic malabsorption of calcium and vitamin D, increasing the risk of insufficiency fractures (35)

-

- Testosterone and PSA

-

-

- Hypogonadism is a recognised cause of osteoporosis and vertebral fragility fractures. PSA is checked alongside to screen for prostate cancer before initiating testosterone, which may accelerate tumour growth (36)

-

- Thyroid functions (TSH, T4)

-

-

- Hyperthyroidism increases bone turnover, reducing bone mineral density and predisposing to insufficiency fractures (37)

-

Figure 3: The work up of spinal insufficiency fractures

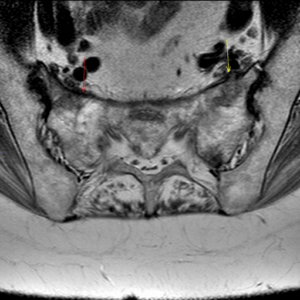

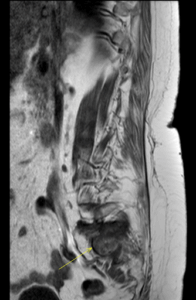

Imaging

Radiographs are a useful initial imaging investigation in patients with a suspected insufficiency fracture and may be the only investigation needed (38). CT or MRI may be utilised in cases of clinical doubt, to exclude other differential diagnoses (39). Bone scintigraphy can be useful to identify multiple foci of disease activity (40).

MDCT is useful as an alternative to bone scintigraphy when radiographs are inconclusive and MRI is not available. It may be used in some centres as an alternative to bone scintigraphy (viii).

DXA scans are useful to ascertain overall bone health and guide secondary prevention management (xxxi).

Radiographs

Standard AP and lateral views of the spine are required to appropriately assess this injury (xxxiv).

Radiographic findings depend on the site of the fracture. Findings include wedge collapse, change in spinal alignment, reduction in vertebral height, sclerosis, bone resorption along the fracture line, bone expansion, exuberant callus and osteolysis (viii) (41).

Increased angulation in anterior posterior direction may highlight an area of disease (42).

X-rays are also useful for pubic ramus fractures which may be associated with spinal insufficiency fractures, and neck of femur fractures (viii).

X-rays have low sensitivity for sacral insufficiency fractures – CT/MRI may be required for diagnosis if suspected.

CT

CT can provide a 2-dimensional representation of spinal fracture and may be helpful in guiding interventional or surgical management and can be used to exclude differential diagnoses (xxxv) (43) . On CT images a linear fracture line with surrounding sclerosis may be observed, but sometimes only sclerosis is demonstrated (viii). CT scan involves ionising radiation, which has the potential to cause biological tissue harm, which is thus a limitation of this imaging modality (xxxix).

MRI

MRI shows decreased bone marrow signal on T1-weighted images and increased signal on T2-weighted images in insufficiency fractures, flattened/wedged vertebral body and altered vertebral alignment (liii).

MRI is highly sensitive and specific but cannot be used in patients with certain implants such as cardiac pacemakers, spinal and deep brain stimulators, a significant limitation in the elderly population.

MRI and CT can be used to exclude differential diagnoses e.g. lytic lesion, inflammatory conditions, Forestier’s disease (younger)/ diffuse idiopathic hyperostosis (DISH) (viii, xxxv).

Multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT)

Multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT) allows 3 dimensional, multiplanar reconstruction, near isotropic three-dimensional reconstructions of anatomical structures. MDCT utilises thin section, high resolution imaging which reduces artifacts and enables visualisation of subtle fracture lines. Thus, MDCT is very specific for the definitive diagnosis of insufficiency fractures of the pelvis but may have limitations in sensitivity. However, MDCT involves significant ionisation radiation which is a major drawback (viii).

Radionuclide scanning (bone scintigraphy):

Bone scintigraphy is a sensitive nuclear imaging technique that uses a radiotracer to assess active bone formation from disease or normal processes.

Radionucleotide scintigraphy can be a useful adjunct to demonstrate areas of disease activity and is particularly helpful in multi-level disease. Hot spots can be identified in vertebral bodies which can indicate disease activity (44).

If a typical pattern of abnormality is not present, the radionuclide bone scan is much less specific. If abnormal or incomplete patterns of uptake are observed, findings may be mistaken for malignancy and other aetiologies. CT or MRI are useful additional imaging techniques in such cases (viii).

DXA

Dual- energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is a technique most commonly used to determine bone mineral density (BMD) in the spine and hip. It is an X-ray based technology but utilises much less ionising radiation making it quite safe (45).

DXA scans are typically indicated after a spinal wedge fracture has been identified to assess bone density in the context of osteoporosis (xxxi). A DXA scan can identify osteopenia and osteoporosis (xxxviii).

The scan reports a T-score and Z-score. A T-score compares bone density to the normal range found in young healthy adults, with values from +1 to -1 being the normal range for a young adult, from -1 to -2.4 indicating osteopenia, and from -2.5 and below indicating osteoporosis. A Z-score compares bone density to people of the same age as the patient. Having a Z score that is lower than expected may require further evaluation for further workup of secondary causes of low bone density (46).

The DXA scan may be used in conjunction with an assessment score as outlined below (47).

| Modality | Role | Notes |

| X-ray | First-line | Often misses early fractures and sacral fractures; may show sclerosis or periosteal reaction vii . Low cost, quick, precise visualisation of fractures/bone disease .Good for assessing vertebral alignment. |

| MRI | Consider differentials | Detects oedema, fracture lines, and differentiates from malignancy xix .

MRI is preferred for pelvic and proximal femur fractures due to superior sensitivity xix. |

| CT | Anatomical clarity | Better for bony detail; useful when MRI is inconclusive xi xii |

| Bone Scan / PET | Metabolic insight | Sensitive for early detection; “Honda sign” on PET is diagnostic for sacral fractures . |

| Ultrasound | Limited role | For superficial bones; may show cortical buckling or callus formation xlix. |

| DXA | Fracture assessment | Calculate T-score, Z-score, and consider fracture risk assessment alongside QFracture® or FRAX®. |

Table 2: Summary of imaging techniques used in spinal insufficiency fractures

Figure 4: MRI showing sacral insufficiency fracture on background of osteoporosis and parathyroidectomy

Figure 5: MRI showing sacral insufficiency fracture on background of osteoporosis and parathyroidectomy

Figure 6: MRI showing sacral insufficiency fracture on background of osteoporosis and parathyroidectomy

Fracture risk assessment scores

QFracture® (https://qfracture.org/) and FRAX® (https://www.fraxplus.org/calculation-tool/) scores are two different scoring system validated in the UK to predict the absolute risk of hip fracture and major osteoporotic fractures (spine, wrist, hip, or shoulder) in the next 10 years, allowing us to make decisions about primary and secondary prevention (57) .

FRAX® estimates the 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture (hip, clinical spine, humerus, or forearm) and hip fracture specifically. It includes demographic details (age, sex, BMI), lifestyle factors (smoking, alcohol), past medical history (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, glucocorticoid use, secondary osteoporosis), and parental history of hip fracture.

Bone Mineral Density (BMD) should be used to refine FRAX score when risk is intermediate or clinical uncertainty exists.

QFracture® uses a broader set of variables and is more UK-specific, incorporating factors such as ethnicity, socioeconomic status (via postcode), and fall history. It classifies inputs into:

- Demographics: age, sex, ethnicity, postcode

- Lifestyle: smoking status, alcohol intake

- Past medical history: falls, cardiovascular disease, asthma, epilepsy, liver disease, cancer, diabetes, Parkinson’s, and others

- Medications: corticosteroids, antidepressants, antiepileptics

- Family history: parental history of osteoporosis

NICE also recommends considering treatment without DXA in:

- Adults ≥75 with prior fragility fracture

- Those at high clinical risk where DXA would not be feasible or affect decision-making (e.g., frail older adults)

Below is a table showing FRAX® and QFracture® risk threshold and associated clinical actions based on NICE guidelines (2023) and relevant UK guidance from the National Osteoporosis Guideline Group (NOGG):

FRAX® / QFracture® Risk Categories and Management Guidance

| Risk Level | 10-Year Risk Estimate (FRAX / QFracture) | Recommended Action |

| Low Risk | <10% (major osteoporotic fracture) | Reassure. Lifestyle advice (diet, exercise, smoking/alcohol reduction). No treatment needed. |

| Intermediate Risk | 10–20% | Consider further investigation, especially BMD via DXA. Treatment may be appropriate based on clinical risk factors and DXA result. |

| High Risk | >20% | Offer treatment (e.g., bisphosphonates) without further testing in most cases. Consider specialist input for younger patients. |

Clinicians must be aware that neither conventional FRAX® nor QFracture® includes dose of corticosteroids, vitamin D levels, or detailed imaging findings. The latest upgrade to FRAX captures this information however it is still not freely available. Furthermore, the risk estimates are probabilistic, not diagnostic, with the purpose of the tools to guide but not to dictate treatment.

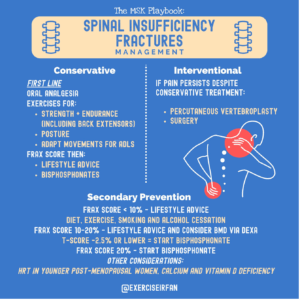

Treatment options

Conservative management:

For many patients, even when conservative treatment is advised the aim is to preserve function, maintain quality of life, and reduce future fracture risk.

Oral analgesia should be used as first line for significant pain. The medication should be regularly reviewed, and analgesia titrated up or down according to response and side effects

According to the National Osteoporosis Guideline Group (NOGG) guidelines (2024), referral to an exercise programme including progressive back muscle strengthening activity as part of general muscle strengthening and/or endurance exercise should be considered. The guidelines also recommend that we offer guidance on how to adapt movements involved in day-to-day living, including how exercises can help with posture and pain.

Secondary fracture prevention should be started following a fracture, with follow-up ideally through fracture liaison services for all postmenopausal women, and men aged 50 years and older, with a newly diagnosed vertebral fracture (58).

Interventional treatment:

Conservative treatment is first line, however a small percentage of patients may be symptomatic and remain in significant pain despite analgesia and exercise. Percutaneous vertebroplasty may be considered as an option for persistent pain and significant functional limitation, especially if the patient was very functionally high performing prior to the incident. Refer to local guidelines and pathways for more information. Other options may be considered by local surgical teams (59, 60).

Secondary prevention:

FRAX and QFracture are the recommended fracture risk assessment tools in the UK. They will be used in conjunction with bone mineral density (BMD) results from axial DXA. BMD measurement is an important part of clinical decision-making. It quantifies the severity of osteoporosis and establishes a baseline for future evaluation of treatment performance. BMD measurement is recommended before osteoporosis drug treatment begins, wherever feasible. A falls risk assessment is also important as most fractures will result from a fall.

According to Royal Osteoporosis Society (ROS) guidelines, Bone mineral density, a prior fracture, age and gender are the most powerful contributors to future fracture risk (61).

Anabolic therapy (e.g. teriparatide, romosozumab) works to increase bone strength by increasing osteoblast activity are recommended for high-risk patients (T score less than -3, multiple osteoporosis fracture, FRAX score higher than expected for age, especially for postmenopausal women who have already sustained a fracture (62)) consider a referral to the local metabolic bone service. Anti-resorptive therapy, such as a bisphosphonate may be offered to people with a BMD T-score of -2.5 or lower, if appropriate and there are no contraindications. Threshold varies for some patients including those prescribed steroids or aromatase inhibitors with T score of -1.5 or lower qualifying for therapy.

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) can be considered in younger postmenopausal women to reduce their risk of osteoporotic fracture, and for the relief of menopausal symptoms.

Risk factors for osteoporosis, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, and calcium and vitamin D deficiency, should be managed if present.

Risk factors for falls should be managed if present (i).

Figure 7: Management of spinal insufficiency fractures

The role of wider multi-disciplinary involvement

Effective management should involve shared decision making, especially regarding pain control strategies and the timing of return to activity or therapeutic exercise (xxiii) (63). Patients in this age group are often dealing with co-morbidities, frailty and polypharmacy and engaging them in these discussions ensures that treatment plans align with their individual goals, functional capacity and support network. In addition, co-ordinated social support plays a vital role in recovery and oftentimes helpful solutions are found in modifying the home environment or domiciliary care.

Early referral to occupational therapy (OT) and physiotherapy (PT) can facilitate safe mobilisation, environmental adaptations, and functional independence. Involvement of PT can further support gradual reconditioning, gait training, and fall prevention strategies (xxvi, xxvii). Recognising and addressing social circumstances such as housing, income, and social support can help prevent recurrence and improve overall quality of life following insufficiency fractures by promoting recovery, independence, and well-being (64).

Nutritional screening and support from dietetics may be appropriate where nutritional deficiencies and dietary concerns exist (65). Where needed, social work input can assist with connecting patients to community services, arranging home care, or facilitating rehabilitation placements.

By addressing these non-medical factors, clinicians can help reduce hospital readmission, promote independence, and improve long-term outcomes (xxvi, xxxi).

Figure 8: MDT considerations for spinal insufficiency fractures

Prognosis

Without appropriate treatment, vertebral fragility fractures can lead to a cascade of consequences, including further fractures, with an increased risk of subsequent vertebral fractures (66).

Progression involves height loss, kyphosis, chronic pain, reduced mobility, and potentially significant functional impairment.

There is also a risk of increased mortality and morbidity, particularly in the elderly, due to immobility related complications such as pneumonia, venous thromboembolism, and deconditioning (67, 68).

Conclusion

Spinal insufficiency fractures can significantly impact quality of life if not managed appropriately. Early recognition is crucial, especially in older patients or those with specific risk factors. A structured approach helps to differentiate benign fractures from a more sinister pathology. Managing the underlying cause, and minimising osteoporosis risk factors are just as important as treating the fracture itself.

- Suspect early in older adults or women with Sudden or rapid onset midline spinal pain, especially with minimal or no trauma

- Screen for red flags including malignancy, infection, and neurological signs

- Use MRI early to confirm diagnosis and rule out serious pathology

- Optimise bone health and address reversible risk factors (e.g. vitamin D, meds)

- Undertake FRAX and consider DXA – aim to commence bone active therapy immediately and consider referral to metabolic bone services for commencement of anabolic therapy

Authors and Affiliations: Dr Imtanaan Abbas, Knievel Mashida, Faisal Shaikh, Muhammad K Nisar, Dr Ryan Linn, Dr Irfan Ahmed

Dr Imtanaan Abbas

Foundation Year 2 Doctor

Hull University Teaching Hospitals

https://www.linkedin.com/in/imtanaan/

Knievel Mashida

Education Academy Fellow

Queen Mary University of London

Dr Irfan Ahmed

Consultant in Musculoskeletal, Sport & Exercise Medicine

www.mskplaybook.com

Faisal Shaikh

Sports and Exercise Medicine Registrar,

Oxford University Hospitals

General Practitioner with Specialist Interest in MSK Medicine

Surrey Community MSK and Pain service

https://www.linkedin.com/in/faisal-bin-muhammad

Muhammad K Nisar

Consultant Rheumatologist & Physician

Bedfordshire Hospitals NHSFT

https://uk.linkedin.com/in/muhammad-nisar-02458284

www.drmuhammadnisar.com

Dr Ryan Linn

FY1 Doctor

University College London

Twitter: @Ryan_Linn_

Dr Oran Roche

Consultant MSK Radiologist

Luton & Dunstable University Hospital

References

- NICE (2017). Overview | Osteoporosis: assessing the risk of fragility fracture | Guidance | NICE. [online] Nice.org.uk. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG146.

- Brennan M, O’Shea PM, O’Keeffe ST, Mulkerrin EC. Spontaneous insufficiency fractures. The Journal of nutrition, health and aging. 2019 Aug 1;23(8):758-60.

- Kanis, J.A., Norton, N., Harvey, N.C., Jacobson, T., Johansson, H., Lorentzon, M., McCloskey, E.V., Willers, C. and Borgström, F. (2021). SCOPE 2021: a new scorecard for osteoporosis in Europe. Archives of Osteoporosis, 16(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-020-00871-9.

- O’Connor, T.J. and Cole, P.A. (2014). Pelvic Insufficiency Fractures. Geriatric Orthopaedic Surgery & Rehabilitation, [online] 5(4), pp.178–190. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2151458514548895.

- Ochi, J., Nozaki, T., Nimura, A., Yamaguchi, T. and Kitamura, N. (2021). Subchondral insufficiency fracture of the knee: review of current concepts and radiological differential diagnoses. Japanese Journal of Radiology, 40(5), pp.443–457. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11604-021-01224-3

- Maier GS, Kolbow K, Lazovic D, Horas K, Roth KE, Seeger JB, Maus U. Risk factors for pelvic insufficiency fractures and outcome after conservative therapy. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics. 2016 Nov 1;67:80-5.

- Daffner RH, Pavlov H (1992) Stress fractures: current concepts. AJR Am J Roentgenol 159(2):245–252. doi:10.2214/ajr.159.2.1632335

- Krestan C, Hojreh A (2009) Imaging of insufficiency fractures. Eur J Radiol 71(3):398–405. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.04.059

- Muthukumar T, Butt SH, Cassar-Pullicino VN (2005) Stress fractures and related disorders in foot and ankle: plain films, scintigraphy, CT, and MR Imaging. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 9(3):210–226. doi:10.1055/s-2005-921941

- Unnanuntana A, Gladnick BP, Donnelly E, Lane JM. The assessment of fracture risk. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010 Mar;92(3):743-53. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00919. PMID: 20194335; PMCID: PMC2827823.

- Gotis-Graham I, McGuigan L, Diamond T, et al. Sacral insufficiency fractures in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg BR 1994;76:882–86

- De Smet AA, Neff JR. Pubic and sacral insufficiency fractures: clinical course and radiologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1985;145:601–06

- Dasgupta B, Shah N, Brown H, et al. Sacral insufficiency fractures: an unsuspected cause of low back pain. Br J Rheumatol 1998;37:789 –93

- Vaishya R, Agarwal AK, Banka PK, Vijay V, Vaish A. Insufficiency Fractures at Unusual Sites: A Case Series. J Orthop Case Rep. 2017 Jul-Aug;7(4):76-79. doi: 10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.862. PMID: 29181361; PMCID: PMC5702713.

- Old JL, Calvert M. Vertebral compression fractures in the elderly. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:111–6.

- Tarantino, U., Baldi, J., Celi, M., Rao, C., Liuni, F.M., Iundusi, R. and Gasbarra, E. (2013). Osteoporosis and sarcopenia: the connections. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, [online] 25(S1), pp.93–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-013-0097-7.

- Coleman RE. Clinical features of metastatic bone disease and risk of skeletal morbidity. Clinical cancer research. 2006 Oct 15;12(20):6243s-9s.

- Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Oden A, Melton LJ, Khaltaev N. European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30(1):3–44.

- Mikula, A.L., Hetzel, S.J., Binkley, N. and Anderson, P.A. (2017). Validity of height loss as a predictor for prevalent vertebral fractures, low bone mineral density, and vitamin D deficiency. Osteoporosis International, [online] 28(5), pp.1659–1665. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-017-3937-z.

- Cabarrus MC, Ambekar A, Lu Y, Link TM (2008) MRI and CT of insufficiency fractures of the pelvis and the proximal femur. AJR Am J Roentgenol 191(4):995–1001. doi:10.2214/AJR.07.3714

- Newhouse KE, El-Khoury GY, Buckwalter JA. Occult sacral fractures in osteopenic patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1992;74:1472–77

- Lundin B, Bjorkholm E, Lundell M, et al. Insufficiency fractures of the sacrum after radiotherapy for gynaecological malignancy. Acta Oncol 1990;29:211–15

- Downie, A., Williams, C.M., Henschke, N., Hancock, M.J., Ostelo, R.W.J.G., de Vet, H.C.W., Macaskill, P., Irwig, L., van Tulder, M.W., Koes, B.W. and Maher, C.G. (2013). Red flags to screen for malignancy and fracture in patients with low back pain: systematic review. BMJ, [online] 347(dec11 1), pp.f7095–f7095. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f7095.

- Finucane, L.M., Downie, A., Mercer, C., Greenhalgh, S.M., Boissonnault, W.G., Pool-Goudzwaard, A.L., Beneciuk, J.M., Leech, R.L. and Selfe, J. (2020). International Framework for Red Flags for Potential Serious Spinal Pathologies. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, [online] 50(7), pp.350–372. doi:https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2020.9971.

- Verhagen, A.P., Downie, A., Popal, N., Maher, C. and Koes, B.W. (2016). Red flags presented in current low back pain guidelines: a review. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society, 25(9), pp.2788–802. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-016-4684-0.

- Henschke, N., Maher, C.G., Refshauge, K.M., Herbert, R.D., Cumming, R.G., Bleasel, J., York, J., Das, A. and McAuley, J.H. (2009). Prevalence of and screening for serious spinal pathology in patients presenting to primary care settings with acute low back pain. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 60(10), pp.3072–3080. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/art.24853.

- Alexandru, D. and So, W. (2012). Evaluation and Management of Vertebral Compression Fractures. The Permanente Journal, 16(4), pp.46–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.7812/tpp/12-037.

- Silverman SL. The clinical consequences of vertebral compression fracture. Bone. 1992;13(Suppl 2):S27–31.

- Langdon J, Way A, Heaton S, Bernard J, Molloy S. Vertebral compression fractures–new clinical signs to aid diagnosis. The Annals of The Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2010 Mar;92(2):163-6.

- Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–56.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyère O, Cederholm T, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(1):16–31.

- Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(18):1860–75.

- Kanis JA, Cooper C, Rizzoli R, Reginster JY. European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(1):23–57.

- Proietti M, Perrone M, Lorenzetti M, Di Renzi P, Valente S, Sagliocca L. Fever and back pain: a diagnostic challenge. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17(1):28–31.

- Duerksen, D., Pinto-Sanchez, M.I., Anca, A., Schnetzler, J., Case, S., Zelin, J., Smallwood, A., Turner, J., Verdú, E., J Decker Butzner and Rashid, M. (2018). Management of bone health in patients with celiac disease: Practical guide for clinicians. Canadian Family Physician, [online] 64(6), p.433. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5999247/ [Accessed 5 Jul. 2025].

- Dandona, P. and Rosenberg, M.T. (2010). A practical guide to male hypogonadism in the primary care setting. International journal of clinical practice, [online] 64(6), pp.682–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02355.x.

- Gorka, J., Taylor-Gjevre, R.M. and Arnason, T. (2013). Metabolic and Clinical Consequences of Hyperthyroidism on Bone Density. International Journal of Endocrinology, 2013, pp.1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/638727.

- Das, C., Baruah, U. and Panda, A. (2014). Imaging of vertebral fractures. Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, [online] 18(3), p.295. doi:https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8210.131140.

- Ruiz Santiago, F., Láinez Ramos-Bossini, A.J., Wáng, Y.X.J., Martínez Barbero, J.P., Espinosa, J.G. and Martínez Martínez, A. (2022). The value of magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography in the study of spinal disorders. Quantitative Imaging in Medicine and Surgery, [online] 12(7), pp.3947–3986. doi:https://doi.org/10.21037/qims-2022-04.

- Askari, E., Shakeri, S., Hessamoddin Roustaei, Fotouhi, M., Sadeghi, R., Harsini, S. and Vali, R. (2024). Superscan Pattern on Bone Scintigraphy: A Comprehensive Review. Diagnostics, [online] 14(19), pp.2229–2229. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14192229.

- Miao, K.H., Miao, J.H., Belani, P., Dayan, E., Carlon, T.A., Turgut Bora Cengiz and Finkelstein, M. (2024). Radiological Diagnosis and Advances in Imaging of Vertebral Compression Fractures. Journal of Imaging, 10(10), pp.244–244. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/jimaging10100244.

- Agrawal, K. and Komal Bishnoi (2023). Insufficiency Fractures. Springer eBooks, pp.1–5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32256-4_230-1.

- Patel, P.R. and De Jesus, O. (2023). CT Scan. [online] PubMed. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567796/ [Accessed 12 Apr. 2025]

- Van den Wyngaert, T., Strobel, K., Kampen, W.U., Kuwert, T., van der Bruggen, W., Mohan, H.K., Gnanasegaran, G., Delgado-Bolton, R., Weber, W.A., Beheshti, M., Langsteger, W., Giammarile, F., Mottaghy, F.M. and Paycha, F. (2016). The EANM practice guidelines for bone scintigraphy. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, [online] 43(9), pp.1723–1738. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-016-3415-4.

- Laskey, M.A. (1996). Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and body composition. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.), [online] 12(1), pp.45–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0899-9007(95)00017-8.

- Royal Osteoporosis Society (n.d.). Osteoporosis: Bone density scan DEXA. [online] theros.org.uk. Available at: https://theros.org.uk/information-and-support/osteoporosis/scans-tests-and-results/bone-density-scan-dxa/.

- Varacallo, M., Seaman, T.J., Jandu, J.S. and Pizzutillo, P. (2023). Osteopenia. [online] PubMed. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499878/ [Accessed 12 Apr. 2025]

- Lyders EM, Whitlow CT, Baker MD, Morris PP. Imaging and treatment of sacral insufficiency fractures. American journal of neuroradiology. 2010 Feb 1;31(2):201-10.

- Ou, X. et al. (2021) ‘Recent development in X-ray imaging technology: Future and challenges’, Research, 2021. doi:10.34133/2021/9892152.

- Spiegl UJA, Beisse R, Hauck S et al (2009) Value of MRI imaging prior to a kyphoplasty for osteoporotic insufficiency fractures. Eur Spine J 18(9):1287–1292

- Matcuk GR, Mahanty SR, Skalski MR, Patel DB, White EA, Gottsegen CJ. Stress fractures: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, imaging features, and treatment options. Emergency radiology. 2016 Aug;23:365-75.

- Featherstone T. Magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of sacral stress fracture. Br J Sports Med 1999;33:276 –77

- Sofka CM (2006) Imaging of stress fractures. Clin Sports Med 25(1):53–62. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2005.08.009.

- Ries T. Detection of osteoporotic sacral fractures with radionuclides. Radiology 1983;146:783–85

- Fujii M, Abe K, Hayashi K, Kosuda S, Yano F, Watanabe S, Katagiri S, Ka WJ, Tominaga S (2005) Honda sign and variants in patients suspected of having a sacral insufficiency fracture. Clin Nucl Med 30(3):165–169

- Joshi P, Lele V, Gandhi R, Parab A (2012) Honda sign on 18-FDG PET/CT in a case of lymphoma leading to incidental detection of sacral insufficiency fracture. J Clin Imaging Sci 2:29. doi:10.4103/2156-7514.96544

- NICE (2023). CKS is only available in the UK. [online] NICE. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/osteoporosis-prevention-of-fragility-fractures/management/assessment/.

- National Osteoporosis Guideline Group (2024). Section 8: Management of symptomatic osteoporotic vertebral fractures. [online] www.nogg.org.uk. Available at: https://www.nogg.org.uk/full-guideline/section-8-management-symptomatic-osteoporotic-vertebral-fractures.

- NICE (2003). 2 The procedure | Percutaneous vertebroplasty | Guidance | NICE. [online] Nice.org.uk. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg12/chapter/2-The-procedure#indications [Accessed 27 Apr. 2025].

- The Royal Orthopaedic Hospital (n.d.). Royal Orthopaedic Hospital – Vertebroplasty. [online] roh.nhs.uk. Available at: https://roh.nhs.uk/services-information/oncology/vertebroplasty [Accessed 14 Jun. 2025].

- ROS (2019). Effective Secondary Prevention of Fragility Fractures: Clinical Standards for Fracture Liaison Services. [online] Available at: https://theros.org.uk/media/1eubz33w/ros-clinical-standards-for-fracture-liaison-services-august-2019.pdf [Accessed 27 Apr. 2025].

Davies AM (1990) Stress lesions of bone. Curr Imaging 2:209–216

Bennell K, Matheson G, Meeuwisse W, Brukner P (1999) Risk factors for stress fractures. Sports Med 28(2):91–122

Wild A, Jaeger M, Haak H, et al. Sacral insufficiency fracture: an unsuspected cause of low back pain in elderly women. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2002;122:58 –60

Rawlings CE, 3rd, Wilkins RH, Martinez S, et al. Osteoporotic sacral fractures: a clinical study. Neurosurgery 1988;22:72–76

Urits I, Orhurhu V, Callan J, Maganty NV, Pousti S, Simopoulos T, Yazdi C, Kaye RJ, Eng LK, Kaye AD, Manchikanti L. Sacral insufficiency fractures: a review of risk factors, clinical presentation, and management. Current pain and headache reports. 2020 Mar;24:1-9.

Expert Panel on Musculoskeletal Imaging, Bencardino JT, Stone TJ, Roberts CC, Appel M, Baccei SJ, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria® stress (fatigue/insufficiency) fracture, including sacrum, excluding other vertebrae. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14:S293–306.

NICE (2012). Osteoporosis: assessing the risk of Osteoporosis: assessing the risk of fr fragility fr agility fracture acture Clinical guideline. [online] Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg146/resources/osteoporosis-assessing-the-risk-of-fragility-fracture-pdf-35109574194373.

- Bandeira, L. and Lewiecki, E.M. (2022). Anabolic therapy for osteoporosis: update on efficacy and safety. Arch. Endocrinol. Metab., [online] 66(5), pp.707–716. doi:https://doi.org/10.20945/2359-3997000000566.

- Wong CC, McGirt MJ. Vertebral compression fractures: a review of current management and multimodal therapy. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2013;6:205–14. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3693826/

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2008. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-IER-CSDH-08.1 [Accessed 8 June 2025].

- Morley, J.E., Argiles, J.M., Evans, W.J., et al. (2010) ‘Nutritional recommendations for the management of sarcopenia’, Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 11(6), pp. 391–396.

- Lindsay, R. (2001). Risk of New Vertebral Fracture in the Year Following a Fracture. JAMA, [online] 285(3), p.320. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.285.3.320.

- Kado, D.M. (1999). Vertebral Fractures and Mortality in Older Women. Archives of Internal Medicine, 159(11), p.1215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.159.11.1215.

- Bliuc, D. (2009). Mortality Risk Associated With Low-Trauma Osteoporotic Fracture and Subsequent Fracture in Men and Women. JAMA, 301(5), p.513. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.50.