Key words: Athletic Injuries; Running; Sporting injuries; Sports medicine

This blog is based on a recently published BJSM study (1).

Why is this study important?

Running continues to grow in popularity worldwide—celebrated for its health benefits and accessibility. Although it also comes with a downside: the risk of injuries. Up to half of all runners report an injury each year, many of them overuse-related. Traditionally, clinicians and coaches have focused on gradual increases in weekly mileage and workload ratios (like the acute:chronic workload ratio, or ACWR) to reduce injury risk.

However, these traditional approaches are overlooking something crucial. Despite widespread use in science and wearable technology, these weekly-based calculations may not accurately reflect the moment-to-moment load decisions runners actually make. In practice, injuries may strike more “suddenly” for instance after a single ill-judged running session that is longer than usual. Equipped with this novel hypothesis, the present study offers a paradigm-shift by focusing on single-session spikes in running distance, rather than week-to-week trends.

How did the study go about this?

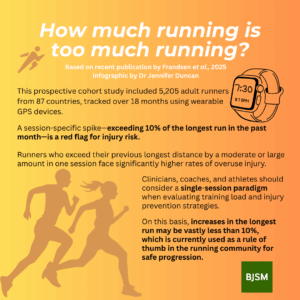

This prospective cohort study included 5,205 adult runners from 87 countries, tracked over 18 months using wearable GPS devices (Garmin). More than 35% of the runners sustained a self-reported running-related injury in the 588,000 running sessions that were analyzed. Of these, a majority were classified as being based on overuse.

Researchers examined three ways of defining a “spike” in running distance:

- Sudden Session-specific spikes: Distance of a single run compared with the longest run in the past 30 days

- Gradual spikes using ACWR: One-week total compared with the average of the previous three weeks

- Gradual spikes using week-to-week change: Comparison of weekly totals between consecutive weeks

In all three approaches, spikes were categorized into one of the following categories after each running session: (1) Regression/small change (≤10%) – reference group; (2) Small spike (>10–30%); (3) Moderate spike (>30–100%); and (4) Large spike (>100%)

What did the study find?

The key finding? Injuries did not develop gradually over weeks of running as previously suggested but peaked when a runner ramped up the distance in a single session as large jumps in distance during a single session significantly increased hazard rate (HRR).

- Small spikes (>10–30%) increased injury rate by 64% (HRR = 1.64)

- Moderate spikes (>30–100%) increased rate by 52% (HRR = 1.52)

- Large spikes (>100%) more than doubled the rate (HRR = 2.28)

In contrast, no clear association was found for ACWR or week-to-week changes—challenging the common belief that weekly progression is a reliable indicator of injury. Collectively, these findings overturn research we and others have been doing for 20 years or more.

What are the key take-home points?

- A session-specific spike—exceeding 10% of the longest run in the past month—is a red flag for injury risk.

- Runners who exceed their previous longest distance by a moderate or large amount in one session face significantly higher rates of overuse injury.

- Week-to-week mileage changes and ACWR may be less reliable indicators of injury risk than previously thought.

- Clinicians, coaches, and athletes should consider a single-session paradigm when evaluating training load and injury prevention strategies.

- An increase between 1% and 10% in distance also carries a risk of injury. On this basis, increases in the longest run may be vastly less than 10%, which is currently used as a rule of thumb in the running community for safe progression.

If confirmed in other studies using e.g. triangulation, this study—based on one of the largest and most comprehensive datasets of midlife recreational runners to date—offers a valuable, evidence-based tool for safer progression in the longest single-session running distance. training. It’s time to rethink how we define “too much” running.

Authors of blog post:

Ida Lindman and Rasmus Østergaard Nielsen

Authors of original article:

Jesper Schuster Brandt Frandsen

Adam Hulme

Erik Thorlund Parner

Merete Møller

Ida Lindman

Josefin Abrahamson

Nina Sjørup Simonsen

Julie Sandell Jacobsen

Daniel Ramskov

Sebastian Skejø

Laurent Malisoux

Michael Lejbach Bertelsen

Rasmus Oestergaard Nielsen

References:

Schuster Brandt Frandsen J, Hulme A, Parner ET, et alHow much running is too much? Identifying high-risk running sessions in a 5200-person cohort study British Journal of Sports Medicine 2025;59:1203-1210.