Introduction

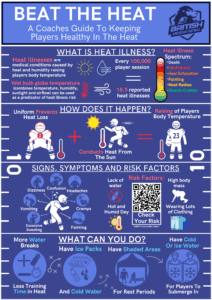

External heat illnesses (EHI) are a prevalent problem in American football globally due to the sports scheduling, high physical demands and protective equipment. Preventing EHI by understanding, recognizing and managing symptoms can improve players’ health and save lives. Therefore, this blog explores the causes, symptoms, risk factors, and preventive measures to help players, coaches, and medical staff mitigate the dangers of EHI.

External Heat Illnesses in American Football

EHI can occur due to external heat factors (humidity, temperature and UV) raising internal body temperatures (1). EHI in American football (AF) players can range from muscle cramps to heat stroke (2). Due to games occurring in summer and insufficient funding for effective counter measures, UK players are at greater risk. A high wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT) is a strong predictor of EHI. In AF, for every 100,000 athlete exposures (one practice or game per player), 15.5 EHI are reported, approximately 11 above other sports averages (1).

AF uniforms (helmets shoulder pads) cause difficulties regulating body temperature. AF uniform hinders natural physiological cooling processes (radiation and evaporation), and a hot and humid microenvironment is created. This causes increased metabolic heat production. These factors increase AF players body temperature, and likelihood of EHI (3).

Severities, Signs and Symptoms:

EHI occurs at varying severities, with different health consequences. EHI has mild conditions including muscular cramps and rashes, likely treatable with little intervention. Heat syncope and heat exhaustion can occur, causing fainting, extreme fatigue, nausea and headaches. When most severe, heat stroke occurs, causing seizures, extreme tachycardia and hyperventilation. Heat stroke can be life threatening, causing many fatalities (1,2)

Detecting signs and symptoms can allow for early medical intervention and improve players’ prognosis. Below is a table of different signs a symptom a player may experience (1,2).

| Mild | Moderate | Severe |

| Muscle Cramps | Pale clammy Skin | Confusion |

| Dizziness | Weak Tachycardic Pulse | Aggression |

| Headaches | Excessive Sweating | Nausea/Vomiting |

| Red moist skin | Fainting | Seizures/Comas |

| Light-headedness | Excessive fatigue | Ataxia- |

Risk Factors

Many risk factors increase EHI risk. Modifiable factors include dehydration, excessive clothing and low cardiovascular fitness. Non modifiable factors include hot and humid environments, taking medications (antidepressants, diuretics, beta-blockers) and high body mass (1,2). Whilst body mass can be altered, many players need higher levels to be effective at their position.

Interventions to prevent EHI

Interventions can prevent EHI. WBGT monitoring can reduce players’ risk, via applying appropriate interventions (4). Risk of EHI can be monitored here (https://arielschecklist.com/wbgt-chart/). Selecting the relevant intervention below can save lives by preventing EHI (4).

Interventions

- Add additional breaks and increase hydration

- Ensures adequate hydration of players and allows time out of the sun

- Make ice packs and cold water readily available

- Placing on the back of the neck can rapidly cool players body temperature

- Have shaded areas available for treatment and for players to stand in

- Allows players to break up time within in the sun

- Have cold water for ready for players to submerge in

Whilst colder water (10oc) is ideal, normal water (~21oc) submersion effectively reduces body temperature (5). Additionally, submerging players in pads and helmets effectively reduces body temperature (5).

Conclusion

In conclusion, many interventions can mitigate the risk of EHI in AF players, ensuring players safety. Recognising risks and effectively implementing interventions allows for continued performance and health of all involved.

Author

Nicholas Tolliday

University of Exeter, Sport and Health Sciences

No competing Interests

References

- Roberts WO, Armstrong LE, Sawka MN, Yeargin SW, Heled Y, O’Connor FG. ACSM Expert Consensus Statement on Exertional Heat Illness: Recognition, Management, and Return to Activity. Curr Sports Med Rep [Internet]. 2021 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Jan 9];20(9):470–84. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/acsm-csmr/fulltext/2021/09000/acsm_expert_consensus_statement_on_exertional_heat.10.aspx

- Gauer R, Meyers BK. Heat-Related Illnesses. Am Fam Physician [Internet]. 2019 Apr 15 [cited 2025 Jan 9];99(8):482–9. Available from: https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2019/0415/p482.html

- Johnson EC, Ganio MS, Lee EC, Lopez RM, McDermott BP, Casa DJ, et al. Perceptual Responses While Wearing an American Football Uniform in the Heat. J Athl Train [Internet]. 2010 Mar [cited 2025 Jan 9];45(2):107. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2838462/

- Kerr ZY, Marshall SW, Comstock RD, Casa DJ. Implementing exertional heat illness prevention strategies in US high school football. Med Sci Sports Exerc [Internet]. 2014 Jan [cited 2025 Jan 9];46(1):124–30. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/acsm-msse/fulltext/2014/01000/implementing_exertional_heat_illness_prevention.18.aspx

- Miller KC, Truxton T, Long B. Temperate-Water Immersion as a Treatment for Hyperthermic Humans Wearing American Football Uniforms. J Athl Train [Internet]. 2017 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Jan 9];52(8):747–52. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28715283/