Keywords: Femoroacetabular Impingement Syndrome (FAIS), Mental Health, Hip Arthroscopy

Femoral acetabular impingement syndrome (FAIS) was a condition I knew little about. I was completely unprepared for the challenges it would bring.

I boarded a 26-hour flight as a fit and active football enthusiast, but by the time I landed, I was faced with unexpected hip pain which marked the beginning of a difficult and painful journey. In this reflection, I explore the personal and professional challenges I went through while focusing on mental health and its connection to FAIS, as well as the gaps I found in healthcare support.

The Physical Challenge

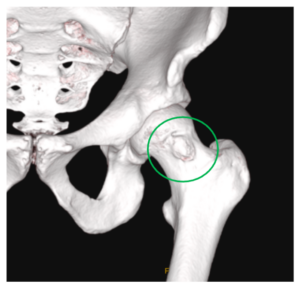

I was diagnosed with hip exostosis (described as a large CAM lesion) with a labral tear. The next six months were a blur of constant discomfort, leading to a significant shift in my lifestyle. I couldn’t sit at a right angle without feeling considerable pain, and my hip refused to heal. My identity as a sports physiotherapist is tied to staying fit and active. This setback affected both my daily life and professional practice, forcing me to find new ways to manage pain and maintain my function. Patients with FAIS often report pain and quality of life scores comparable to older adults with advanced osteoarthritis [1]; this is something I can relate to.

Figure 1. 3D CT scan of my left hip exostosis

The Impact on Mental Health

The change from being active and sporty to dealing with chronic pain was emotionally devastating. My social circles quickly shrank as I withdrew from football and other physical activities. I felt that I had lost my identity overnight. I became anxious and depressed about the uncertainties that lay ahead, and I became fear avoidant as I catastrophised after reading my MRI and CT scan results.

Fast forward two years, and I’m well on my way to recovering from hip arthroscopy, but unfortunately, I’ve hit another hurdle: I developed FAIS in my non-operated hip. My mental health journey continues. My optimism and mental health fluctuate, leading to inconsistency with my rehabilitation efforts. Only 57% of hip arthroscopy patients return to their pre-injury level of sport, and just 17% achieve optimal performance [2]. I’ve lost hope that I will ever come close to my previous sporting capabilities.

Despite showing visible signs of anxiety and depression, I received no mental health screening from the various healthcare professionals (physiotherapists, sports doctorsdoctor and surgeons) I visited.

Expert consensus suggests that comorbidities like chronic pain, insomnia, and anxiety can affect both prognosis and treatment effectiveness in FAIS [3]. FAIS patients with mental health disorders typically report lower outcomes before and after hip arthroscopy, with less pronounced improvements compared to those without such disorders [4]. Similarly, patients with minimal to mild depression symptoms have better outcomes and are more likely to benefit from surgery than those with moderate to severe depression [5].

Lately, my mental health and FAIS symptoms have both improved, but it isn’t easy to differentiate the relationship between the two. I believe that addressing my mental health disorders, catastrophising, and fear avoidance earlier would have been significantly beneficial to my progress.

Reflection

- The absence of psychological assessment in my care highlights a gap in addressing the mental health needs of patients dealing with injuries. Psychological screening should be essential to health care professionals’ assessments, particularly for those whose identity and livelihood depend on their physical abilities.

- Integrating a sports psychologist and psychologically informed physiotherapy can support a patient’s mental health, address catastrophizing and fear of movement, and potentially improve patient-reported outcomes.

- Injured health professionals may experience heightened anxiety and fear about their recovery due to their awareness of long-term implications.

- Honest, empathetic discussions are crucial to explaining that athletes may not return to their previous level of performance and educating them on the long-term implications of FAIS.

Author: Matt Farrimond

Physiotherapist at UniSports Physiotherapy, Auckland and currently undertaking a Post-Graduate Certificate in Sports Physiotherapy at the School of Physiotherapy, University of Otago, New Zealand.

No competing interests

References

- Kemp JL, Makdissi M, Schache AG, Pritchard MG, Pollard TCB, Crossley KM. Hip chondropathy at arthroscopy: prevalence and relationship to labral pathology, femoroacetabular impingement and patient-reported outcomes. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(14):1102-7.

- Ishøi L, Thorborg K, Kraemer O, Hölmich P. Return to sport and performance after hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement in 18- to 30-year-old athletes: A cross-sectional cohort study of 189 athletes. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2018;46(11):2578-87.

- Kemp JL, Risberg MA, Mosler A, Harris-Hayes M, Serner A, Moksnes H, et al. Physiotherapist-led treatment for young to middle-aged active adults with hip-related pain: consensus recommendations from the International Hip-related Pain Research Network, Zurich 2018. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(9):504-11.

- Lansdown DA, Ukwuani G, Kuhns B, Harris JD, Nho SJ. Self-reported mental disorders negatively influence surgical outcomes after arthroscopic treatment of femoroacetabular impingement. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 2018;6(5):232596711877331.

- Sochacki KR, Brown L, Cenkus K, Di Stasi S, Harris JD, Ellis TJ. Preoperative depression is negatively associated with function and predicts poorer outcomes after hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement. Arthroscopy. 2018;34(8):2368-74.