Authors: Jodie G. Dakic, Jean Hay-Smith, Kuan-Yin Lin Jill Cook, Helena C. Frawley

This blog provides an overview of a recent BJSM study.

Why is this study important?

One in three women across all sports experience pelvic floor symptoms such as leaking urine (1). Up to 80% of female athletes participating in high-impact or strenuous sports such as trampolining (2), gymnastics (3) and weight-lifting (4) leak urine, wind or stool. Approximately half of the women who experience pelvic floor symptoms during sport or exercise stop participating (5). A majority of female athletes with pelvic floor symptoms choose not to tell anyone about their symptoms, limiting their access to help (3, 6).

This study provides important insights from the perspective of symptomatic Australian women, giving them a voice in shaping best practice for pelvic floor symptom screening in sports and exercise settings. It emphasises the importance of conducting screening in a sensitive and respectful manner to empower women to discuss their symptoms. By implementing suitable screening practices, health and exercise professionals can help women access treatment for their symptoms, allowing them to continue participating in sports and exercise throughout their lives.

How did the study go about this?

We conducted an explanatory, sequential, mixed-methods study (7, 8). Firstly, we surveyed 4,556 adult, Australian women who had experienced pelvic floor symptoms and asked about their experience of pelvic floor symptom disclosure and screening within sports and exercise settings. We also asked about their preferences for future pelvic floor screening and management practices. Preliminary survey data analysis revealed findings that required more in-depth exploration and this guided our study design for the qualitative phase. In the second phase, we conducted online, one-one interviews with a subset of survey participants (n=23). We integrated the quantitative and qualitative data, using a method called ‘following a thread’ (8, 9) to gain a greater depth of understanding of pelvic floor screening practices from the perspective of symptomatic women.

What did the study find?

Three main ‘threads’ were identified.

Thread one: Women (not) telling.

A majority of the women had not disclosed their pelvic floor symptoms to anyone in a sport or exercise setting. The reasons for non-disclosure included feelings of shame and embarrassment, a lack of knowledge about pelvic health, and a reluctance to initiate a conversation about their symptoms. Women were not sure who to tell, were unaware of treatment options and had not been asked by anyone about their symptoms.

Thread Two: Screening for pelvic floor symptoms.

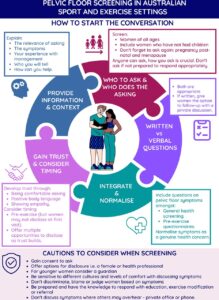

Only a quarter of women had ever been asked about their pelvic floor symptoms. Overall, women supported the inclusion of pelvic floor symptom screening in sport and exercise settings, but only if it is conducted in a sensitive and supportive manner. Professionals should demonstrate knowledge, empathy, describe benefits of telling and obtain informed consent prior to asking a direct question. Including pelvic floor symptom questions within existing pre-exercise and general health screening practices was suggested as a way to normalise the topic as a genuine health concern and reduce the stigma of discussing pelvic health in sport settings. Professionals should be aware that it takes courage and the development of trust before many women feel comfortable to talk about their symptoms and so offering multiple points for disclosure was suggested. Participants endorsed women of all ages being screened for symptoms, but for younger adolescent women, having a guardian present may need to be considered. In particular, women who engage in high-impact sports and those who are pregnant, post-partum, menopausal or returning to exercise after injury or time away from physical exercise, could be asked about their pelvic floor health.

Thread Three: Creating safe sports environments

The exercise environment influenced whether women continued to participate or stop. Women endorsed sport and exercise professionals receiving appropriate training, so they could raise pelvic health awareness and promote a supportive and safe sports culture. Ways professionals could promote a pelvic health safe sports culture included providing education, displaying comfort and genuine interest, and offering advice, exercise modifications, or referrals as needed and within their scope of practice. Women suggested, as with menstrual health, sports organisations could have containment products e.g. pads and underwear available in changerooms. Organisations could also consider uniform requirements that allowed for concealment of a pad or accidental leakage.

What are the key take-home points?

Pelvic floor symptoms often lead women to discontinue sports and exercise, commonly without telling anyone about their symptoms. This research provides guidance on best practices for pelvic floor symptom screening and provides practical recommendations for improving pelvic health practices in sport and exercise settings to support women’s participation and well-being. Women support health and exercise professionals initiating pelvic health conversations within sports and exercise settings but emphasise the importance of sensitive and respectful screening, followed by an ability to provide a knowledgeable and appropriate response.

In summary, this study sheds light on the need for improved screening practices to address pelvic floor symptoms in sport and exercise settings, with a focus on ensuring women feel safe and supported when discussing these sensitive issues with health and exercise professionals.

Funding: This research was supported by funding from the Physiotherapy Research Foundation Seeding Grant (Grant number: S17-011 [questionnaire]) and the Australian Bladder Foundation Grant (no grant number) managed by the Continence Foundation of Australia (questionnaire and qualitative study).

References:

- Teixeira RV, Colla C, Sbruzzi G, Mallmann A, Paiva LL. Prevalence of urinary incontinence in female athletes: a systematic review with meta-analysis. International Urogynecology Journal. 2018;29(12):1717-25.

- de Mattos Lourenco TR, Matsuoka PK, Baracat EC, Haddad JM. Urinary incontinence in female athletes: a systematic review. International Urogynecology Journal. 2018;29(12):1757-63.

- Skaug KL, Engh ME, Frawley H, Bø K. Urinary and anal incontinence among female gymnasts and cheerleaders—bother and associated factors. A cross-sectional study. International Urogynecology Journal. 2022;33(4):955-64.

- Skaug KL, Ellstrom Engh M, Frawley H, Bo K. Prevalence of pelvic floor dysfunction, bother and risk factors and knowledge of the pelvic floor muscles in Norwegian male and female powerlifters and Olympic weightlifters. J Strength Cond Res. 2020;36(10):2800-7.

- Dakic JG, Cook J, Hay-Smith J, Lin K-Y, Frawley H. Pelvic floor disorders stop women exercising: a survey of 4556 symptomatic women. J Sci Med Sport. 2021;24(12):1211-7.

- Thyssen HH, Clevin L, Olesen S, Lose G. Urinary incontinence in elite female athletes and dancers. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2002;13(1):15-7.

- Creswell JW, Plano Clark V. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Third ed. USA: Sage.; 2018.

- O’Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies. BMJ. 2010;341:c4587.

- Moran-Ellis J, Alexander VD, Cronin A, Dickinson M, Fielding J, Sleney J, et al. Triangulation and integration: processes, claims and implications. Qualitative Research. 2006;6(1):45-59.