Sport offers a unique combination of mental and physical health benefits and should be a routine component of aid in refugee contexts.

In this blog we explain that the plight of refugees has rarely been more publicly visible than it is today. With the complex challenges refugees face, sport can be the missing piece to typical, survival-oriented humanitarian aid.

Refugees and Humanitarian Aid

In 2021, over 84 million people worldwide were forced or obliged to leave their homes (UNHCR, 2021). Included in this displaced population are refugees, who “have fled war, violence, conflict or persecution and have crossed an international border to find safety in another country” (UNHCR, 2021). These individuals and families have unique and often traumatising experiences that force them to leave their homes. Traveling sometimes hundreds of miles to seek safety and resettling in a new place and culture, refugees can develop physical and mental health issues that threaten their overall well-being [1,2]. It can be difficult for refugees to seek help for such issues whilst fleeing, and even after they’ve arrived at their destination [3]. Immigration policy can also prevent displaced individuals from getting the help they need. This puts additional pressure on global, national, and local non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to step in and help where governmental policies will not.

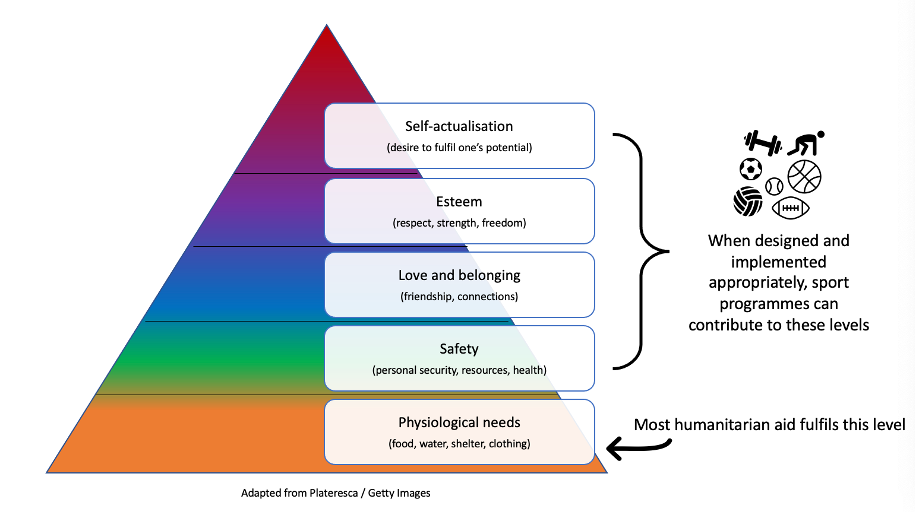

Many humanitarian and/or emergency aid NGOs help meet the basic needs of asylum-seekers and refugees by providing food, water, clothing, and shelter [4]. As Maslow’s hierarchy would have it, aid organisations focus on the pyramid’s foundation by taking care of refugees’ physical survival. While this is undoubtedly necessary, an additional need should also be addressed in humanitarian contexts: refugees’ mental health and psychological-social support (MHPSS) [5].

Refugee Mental Health

Until recently, mental health was hardly a concern for countries hosting refugees—or even refugees themselves. Many refugees are unlikely to seek help for mental health due to cultural stigma, despite having symptoms of severe stress or even post-traumatic stress (PTSD) [2,6]. Again, the top priority for humanitarian NGOs has always been physical survival. But neglecting mental health is arguably as deadly as neglecting physical health. What is needed in humanitarian contexts is a way to address the holistic well-being of refugees, including physical and mental health, and psychosocial support.

The Role of Sport

Enter sport, which is currently the dark horse in humanitarian and MHPSS contexts. Exercise-based programmes have been used for refugees’ mental health improvement [7,8] but sport programmes are not as common. Despite sport’s global reach and popularity, the humanitarian sector rarely considers or utilises it to help refugee populations. Rather, sport is seen as a luxury and an afterthought when compared to food, water, and shelter. The potential of sport to contribute to mental health and psychosocial support outcomes in refugee humanitarian contexts is still quite new and tenuous, as research evidence is playing catch-up to positive, anecdotal evidence (read Peace and Sport; listen to All in the Mind). While the academic literature on the intersection between mental health and refugees is growing [5], once sport is added to the mix, the literature nearly disappears.

Figure 1. An adaptation of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs as it pertains to sport and humanitarian contexts with refugees.

Knowing that sport has not been thoroughly integrated with the humanitarian and MHPSS contexts is both promising and daunting. It is promising because there is, consequently, space for practitioners and researchers to investigate and apply programmes that can support refugees’ holistic well-being. On the other hand, it can be daunting to work with refugees in humanitarian contexts with little evidence to validate one’s work. To merge sport, humanitarianism and MHPSS, an integrated approach with experts from various disciplines (e.g., psychology, sport, public health) is needed. It seems that overarching governing bodies like the United Nations General Secretary and the World Health Organisation recognise the potential of sport, but visible action is still in the works.

A Way Forward

To help stimulate such action, the Olympic Refuge Foundation (ORF) was established by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) after the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro. The ORF’s vision is a ‘society where everyone belongs, through sport’ and its mission is to ‘shape a movement that ensures young people affected by displacement thrive through (safe) sport.’ The ORF also connects sport, sport for development/protection and humanitarian actors through the Sport for Refugees Coalition (co-convened with the IOC, UNHCR and the SCORT Foundation), and runs sport for protection programmes worldwide for young, displaced people and their host communities. A number of ORF initiatives are focused specifically on the role of sport in supporting MHPSS outcomes for young people affected by displacement, including the work of the ORF Think Tank and the ORF funded Game Connect programme in Uganda (delivered by the AVSI Foundation in consortium with Right to Play, Youth Sport Uganda, the Uganda Olympic Committee and UNHCR). The authors’ connections with and knowledge of the ORF sparked the ideas shared in this article.

Conclusion

- When it comes to protecting refugees and asylum seekers’ mental health, services are starkly lacking.

- Sport programming in humanitarian settings is a missing piece to this issue as it can address refugees’ holistic well-being.

- With more people seeking refuge each year, it is crucial that government officials, NGOs, and practitioners take action. Government officials and policies, in countries hosting refugees, must prioritise and (financially) support high-quality sport programmes that promote mental health outcomes.

- Sport-based NGOs and practitioners should consider how they can support young refugees and embed mental well-being in their provisions and programming.

Author names & affiliations:

Anna Farello, Loughborough University London

Dr. Holly Collison-Randall, Loughborough University London

References

1 Hadfield K, Ostrowski A, & Ungar, M. What can we expect of the mental health and well-being of Syrian refugee children and adolescents in Canada? Canadian Psychology-Psychologie Canadienne 2017;58:194-201.

2 Marshall E, Butler K, Roche T, et al. Refugee youth: A review of mental health counselling issues and practices. Canadian Psychology-Psychologie Canadienne 2016;57:308-319.

3 Hebebrand J, Anagnostopoulos D, Eliez S, et al. A first assessment of the needs of young refugees arriving in Europe: What mental health professionals need to know. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2015;25:1-6.

4 Knappe F, Colledge F, & Gerber M. Challenges associated with the implementation of an exercise and sport intervention program in a Greek refugee camp: A report of professional practice. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2019;16: 4926.

5 Kronick R, Jarvis GE, & Kirmayer LJ. Refugee mental health and human rights: A challenge for global mental health. Transcultural Psychiatry 2021;58:147.

6 Kim W, Yalim AC, & Kim I. “Mental health is for crazy people”: Perceptions and barriers to mental health service use among refugees from Burma. Community Mental Health Journal 2020;57:965-972.

7 Adamakis M. Promoting physical activity for mental health in a refugee camp: The Skaramagas project. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2022;56:115.

8 Liedl A, Müller J, Morina N, et al. Physical activity within a CBT intervention improves coping with pain in traumatized refugees: Results of a randomized controlled design. Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass.) 2011;12:234-245.