Is the patellofemoral contact area influencing the choice of my exercise plan? Part of the BJSM’s Young Clinician Blog Series – to contribute please email bjsmblog@bmj.com

PFP is a common debilitating knee joint pathology affecting both active and sedentary people with age ranging from 10 to 50 y.o. Altered joint mechanics, quadriceps muscles inhibition, increased foot pronation, hip adduction and/or femur internal rotation are potentially a series of causes leading to the pathology.

A recent meta-analysis published on the BJSM reviewed the effectiveness of education, physical therapy, patella taping/mobilisations, orthosis and “wait and see” approaches in the treatment of PFP.

The findings are:

- Education and physical therapy are most likely to be effective at 3 months follow up

- At 12 months both education and physical therapy are confirmed to be effective treatments (with a good possibility that education alone could maintain the improvements)

- Orthosis and education combined are as effective as the combination of exercise, education and patellar treatments

- There is insufficient evidence to support a specific exercise choice

- “Wait and see” approach is not effective

Recommended Physical therapy is characterised by:

- Hip strengthening exercises

- Trunk strengthening exercises

- Knee strengthening exercises

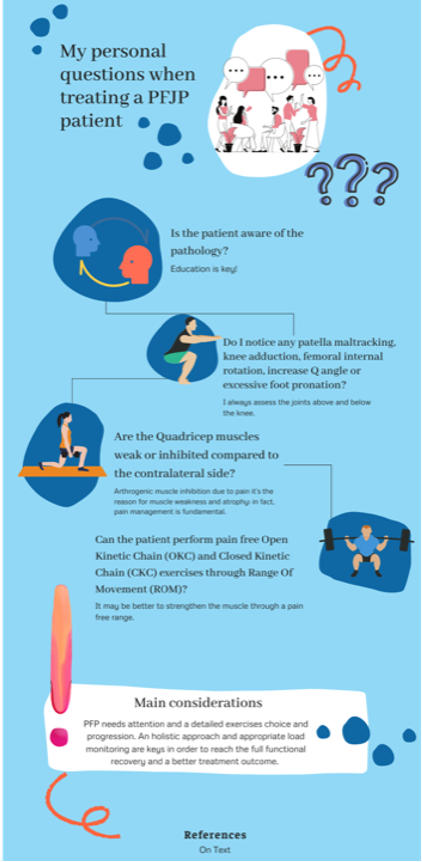

My personal questions when treating a PFJP patient:

- Is the patient aware of the pathology? If not, education is key!

- How does the patient move? Do I notice any patella maltracking, knee adduction, femoral internal rotation, increase Q angle or excessive foot pronation? I always assess the joints above and below the knee.

- Are the Quadricep muscles weak or inhibited compared to the contralateral side? Arthrogenic muscle inhibition due to pain can be the reason for muscle weakness and atrophy; in fact, pain management is fundamental before muscle strengthening and load exposure.

- Can the patient perform pain free Open Kinetic Chain (OKC) and Closed Kinetic Chain (CKC) exercises through Range Of Movement (ROM)?

How do I approach these findings?

- Patients need to be educated; in fact, I personally like to explain them the pathology and the injury location in the knee by showing anatomy pictures of the interested joint.

- When assessing movement quality in patients with PFP the main dysfunctional movement pattern leading to pain is usually a knee dominant pattern where it is possible to identify a femur internal rotation and knee adduction moment during functional tasks/exercises. Hip external rotators and extensors, such as Gluteus Minimus, Medius, Maximus and the Hamstrings muscle group play such an important role in avoiding the knee to collapse inwards. Thus, it is advised to include their strengthening in the rehab program.

- As we know, quadriceps muscle inhibition in the presence of PFP is common, with the Vastus Medialis (VMO) suffering most. Prior to progress to exercise selection, I assess its function as inhibition and dysfunction can cause patella maltracking. From my anecdotal experience, kinesio-taping and NMES can sometime help with the aim of ‘re-activating’ this inhibited muscle.

- Most of the time patients are not able to perform neither OKC or CKC exercises through range due to pain and Quadriceps inhibition. Here below, I decided to report a couple of examples to explain my approach when selecting the appropriate exercises:

-

- Leg extension is an OKC exercise. I use it to analytically strengthen the Quadricep muscles. PF contact area decreases between 30° to 0° knee flexion so increasing the force through a specific point of the PF joint area. I normally limit the leg extension ROM from 90 to 30 in order to make sure that the patient is pain free while performing the exercise on the machine.

- Leg press is an CKC exercise. I use it to functionally strengthen the Quadricep muscles. PF contact area decreases between 90° to 45° knee flexion so increasing the force through a specific point of the PF joint area. I normally limit the leg press ROM from 45° to 0° in order to make sure that the patient is pain free while performing the exercise on the machine.

To conclude, I do believe PFP needs attention and a detailed exercises choice and progression. As the majority of the pathologies we see, and holistic approach and an appropriate load monitoring are keys in order to reach the full functional recovery and a better treatment outcome.

Author & Affiliation

Marin Vittoria

Physiotherapist at Isokinetic Medical Centre, London

Twitter: @vittomarin

Linkedin: Vittoria Marin

References:

- Buckthorpe M., et al. ASSESSING AND TREATING GLUTEUS MAXIMUS WEAKNESS – A CLINICAL COMMENTAR. IJSPT. 2019; 14(4):655-669.

- Buckthorpe M., Della Villa F., Optimising the ‘Mid-Stage’ Training and Testing Process After ACL Reconstruction. Sport Med. 2019. DOI 10.1007/s40279-019-01222-6

- Buckthorpe M., et al. RESTORING KNEE EXTENSOR STRENGTH AFTER ANTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT RECONSTRUCTION: A CLINICAL COMMENTARY. IJSPT. 2019;14(1):159-172.

- Loudon J., BIOMECHANICS AND PATHOMECHANICS OF THE PATELLOFEMORAL JOINT. IJSPT. 2016; 11(6):820-830

- Winters M., et al. Comparative effectiveness of treatments for patellofemoral pain: a living systematic review with network meta-analysis. BJSM. 2021; 55:369–377