By Adam Weir @adamweirsports

COVID has been a global disaster with mind bogglingly huge impact, for the most part negative. Yet this giant pandemic storm cloud has had a tiny personal silver lining; more time to read and reflect. Inspired by this, and less able to exercise this past week (will become clear below why) I was inspired to write my first BJSM blog. I hope you’ll find it interesting and enjoyable.

My interest in calf muscle injuries was recently rekindled on two fronts; I was asked to prepare medical student teaching on the topic for the autumn, and while trying to set a new PR running in the local dunes I had yet another calf muscle injury. Following multiple previous injuries, 2019 had gone well, after following a rehab program kindly provided by Phil Glasgow @philglasgow. I had been running, skipping rope and feeling 21 again. Then as so often happens, I started scrimping on my maintenance exercises, ignored Tim Gabbets @TimGabbett acute-chronic rules with my jogging progressions – then the tennis leg stuck. You should know better I hear you say… and now I’m forced to agree.

Anyway, back to the point, renewed interest in calf muscle injuries, time on my hands and PubMed led me to an article from the Lancet in 1884.[1] Upon reading it I felt like I struck buried treasure and was inspired to share this. And yes – your eyes are not deceiving you: 1884.

So, what was happening in the world around 1884? Well the world’s first electric streetlight system was just up and running. The Orient express had not long since made its first journey, Greenwich was established as the universal time meridian for longitude and the first patent had just been filed for a mechanical tabulating machine: the start of data processing. Also, tennis was an up and coming sport.

Origins of tennis

Lawn tennis as a game started around 1874, the first iteration of the rules was written in 1875, and the first Wimbledon championships was held already back in 1877. Lawn tennis, to give it its correct name, became very popular in no time, and Dr Wharton P. Hood, who also played himself, wrote his article entitled: “On lawn-tennis leg”, based upon his 14-year clinical experience. The advent of new sports giving rise to new injuries and eponymous names may well have its origins in this article. I couldn’t find an older eponymous sports injury, and even Gamekeeper’s thumbs (ulna collateral injuries of the thumb, now more commonly known as skier’s thumbs in our sports medicine community) were first described as recently as 1955.[2]

Eloquently written and raising many issues that are still the hot topics in contemporary sports medicine, this is a must read 2-page article. The term tennis-leg was used to describe a “rupture of some portion of the muscular or tendinous structure of the calf.” Dr Hood had experienced that athletes of all ages who rested for long periods and used heel raises, often had prolonged recovery together with a high recurrence rate. When recurrence occurred then “a further period of rest was enjoined”. The cycle started again. Instead Dr Hood preferred an active approach and based his treatment “upon two essential points – namely, adequate support for the structures of the calf, coupled with immediate and uninterrupted use of the limb.” More than a century later a recent study in the New England Journal of Medicine shows us that started rehab early as opposed to resting for three weeks leads to a vastly shorter time to return to play.[3]

He continues to describe the treatment – and it would fit perfectly into the PEACE and LOVE strategy described in an earlier BJSM blog by Dubois and Esculier.[4] This nine-point plan forms the framework to discuss Hood’s advice. Rather than paraphrasing, I will let Dr Hood speak with his own beautiful historical voice:

Protect – This is one of the few points where Dr Hood is perhaps more progressive than his contemporary peers. Applying protection was important and using strips of plaster, the calf was supported from “two inches above the ankle-joint to above the thickest part of the calf.” Modern guidelines propose on loading or restricting movement for 1 to 3 days, and here Dr Hood disagrees. He was adamant that patients be encouraged to walk placing the heel on the floor before leaving his office.

Elevate – A beautiful description is given on elevation: “As soon as possible after the occurrence of the rupture, the patient should be placed upon a sofa, with his injured leg raised above the level of his head; and should be kept in this position for five minutes. This is an important preliminary, because the position alone will be sufficient to empty the limb of superfluous blood, and thus to reduce the swelling which is commonly present. A calf which is very much enlarged, and very hard, will frequently return to its natural dimensions within the time specified; and the patient will at once obtain relief from the oftentimes distressing feeling of tension. Moreover, if the elevation of the limb be neglected, the plaster next to be described will soon be loosened by the subsidence of the swelling, and will require to be replaced within a few hours.”

Avoid anti-inflammatory modalities – While Dr Hood wrote his article long before the advent of NSAIDs, inflammation was also a much-feared condition back in the day. Yet is was of little concern to him. He was keen to promote early mobilisation and describes vividly how patients could be resistant to this idea: “Success in walking in the first instance, will depend largely upon the temperament of the injured person. A resolute man, who believes in his doctor, will walk at once, while a more timid patient will require coaxing and urging. The chief trouble will be with the sceptical man, who has his own “view” about injury, and who will express them in such questions as “Well, but do you not think there is a risk of inflaming my leg?”

Compress- With the application of the plaster support and compression were clear aims.: “When the plaster is well adjusted, it disperses the effusion of blood and lymph and restores the natural flow of the circulation; while at the same time it holds all the muscular and tendinous structures firmly together, and practically converts the sound portions into a splint for those which are torn.”

Educate- Unsurprisingly Hood offers an insightful passage into an athletes considerations on injury perception, and once again provides advice that I feel still holds up today: “The elderly man, on the other hand, is probably inclined to think that he has been foolish at this time of life, and with his muscles out of training, to engage in a game requiring active exertion. He regards the accident as a lesson in prudence, is fully alive to the value of a sound limb, and sets himself to nurse the injury, with the idea of obviating the wholly imaginary danger of inflammation, or of retarding union of the ruptured parts. By stripping and compulsory exercise he is, in fact, protected against himself.

Load – Once more we are treated to a brief description of the advantages of avoiding prolonged rest, especially in elderly patients: “In addition to the rapid cure which it affects, to the prevention of loss of health from want of exercise, and of lots of other kinds from absence from business or occupation, my method has the further advantage of diminishing the liability to recurrence of the accident.”

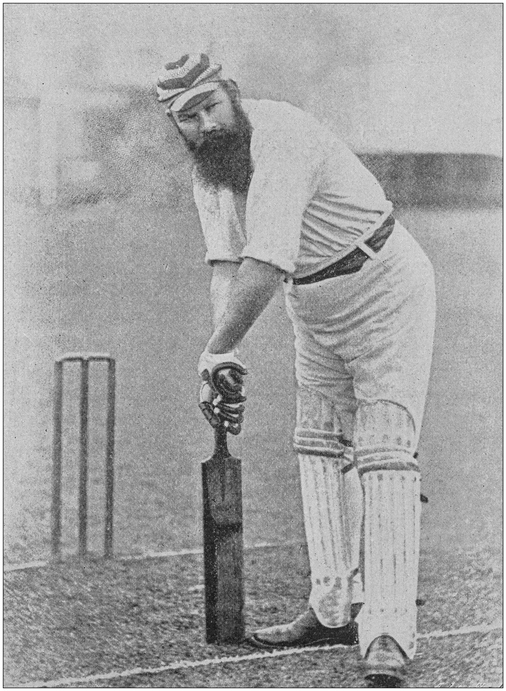

Optimism – The entire article exudes optimism. The final passage illustrates the success with two cases described in more detail. The best described involved Dr W.G.Grace–one of the most celebrated cricketers in the history of English cricket. Besides his cricketing prowess he was also a medical doctor, and when injured he sought out Hood’s assistance. He sustained a tennis leg while playing at Lord’s cricket ground and visited Dr Hood the next morning. He remarked to Dr Hood that he “did not put his heel on the ground to save his life.” He feared he was “done for the season.” Dr Hood expands: “I strapped up the leg, and he walked away, putting his heel fairly to the ground. The next morning he continued his innings, having someone to run for him, and he added 24 runs to his overnight score.”

Vascularisation – As explained above the early mobilization and avoidance of deconditioning was proposed as a method to avoid function and improve work status.

Exercise – Once again it seems we are witnessing the insides of a pioneer. A brief exercise regime is also described: “the amount of walking should be increased daily, and after the third day the patient should go up and down stairs freely in the usual manner. “

1884-2020 – evolution?

On reading this article I was filled with mixed emotions. Admiration and wonder at the clinical insight, and bravery, to publish something pioneering against the grain of the day. At the same time a heavy-hearted sensation and general disappointment. How can it be that “tennis leg”, an injury described this well 136 years ago, in a sport played by 1.2 billion people, still has no clear evidence-based treatment protocol? Please let me know if I’m wrong but to the best of my knowledge there isn’t a single RCT focusing on rehab for calf injuries. So, once the courts open again post-COVID, and it rains tennis legs after our lockdown de-conditioning, for now we can still use much of Hoods 1884 wisdom, backed up by the NEJM RCT, and avoid advising prolonged rest. For now, I’m off to do my rehab and then look for more historical gems – if you know of any please share in the comments section below, or better yet: tweet me @adamweirsports.

Stay safe and strong, Adam.

***

Adam Weir @adamweirsports is a sports medicine physician, keen tennis player and sufferer of multiple muscle injuries in his legs over the years!

Affiliations:

Erasmus MC Center for Groin Injuries, Department of Orthopaedics, Erasmus MC University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Aspetar Sports Groin Pain Centre, Aspetar Orthopaedic and Sports Hospital, Doha, Qatar.

Sport medicine and exercise clinic Haarlem (SBK). Haarlem, The Netherlands.

References

- Hood WhartonP. ON “LAWN-TENNIS LEG.” The Lancet 1884;124:728–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)28325-7

- Campbell CS. Gamekeeper’s thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1955;37-B:148–9.

- Bayer ML, Magnusson SP, Kjaer M. Early versus Delayed Rehabilitation after Acute Muscle Injury. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1300–1. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1708134

- Dubois, Blaise E Jean Francois. Soft tissue injuries simply need PEACE & LOVE. Soft Tissue Inj. Simply Need PEACE LOVE. 2019.https://blogs.bmj.com/bjsm/2019/04/26/soft-tissue-injuries-simply-need-peace-love/ (accessed 19 Apr 2020).