By Christina Le @yegphysio

Return to sport, it’s so hot right now. That’s right Zoolander, move aside for one of the most heavily researched and discussed topics in sports medicine! It seems like a new paper is published nearly every day that tackles some aspect of return to sport (RTS) in athletes who have undergone anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction.

With 88% of athletes expecting to return to their pre-injury sport at their pre-injury level following primary ACL reconstruction,1 it’s not surprising that we’ve looked long and hard to find the perfect RTS formula. Ideally, this formula prepares an athlete to return to their previous level of performance while minimizing the risk of re-injury. And over the past few years, this formula has been revamped to include criterion-based progressions and RTS screening.

Despite these changes, our outcomes still aren’t great. I hate to sound like Debbie Downer but…

That means 1 in 3 athletes fail to RTS within 2 years post-surgery. This mismatch between expectation and reality might contribute to negative health outcomes in the long-term, like increased adiposity, early onset of osteoarthritis, or reduced health-related quality of life.

Most clinicians use RTS criteria in attempt to identify which athletes are at greater risk of suffering a re-injury. But, according to a recent systematic review, there is no association between passing RTS criteria and the incidence of a second ACL injury.2

So, what can we do to help more athletes reach their RTS goals?

Restoring physical attributes such as range of motion or strength has been on the radar for some time now. This is reflected in the growing consensus that “picking heavy ‘stuff’ up and putting it back down” is not only a good thing but a necessary thing for athletes post-ACL injury or reconstruction. It’s also reflected in our RTS screening which typically consists exceeding a certain limb symmetry index for strength and hop tests (which, admittedly, is somewhat flawed in itself).

But as Dr. Clare Ardern advocates, we should also address and treat the psychosocial factors (aka non-physical factors) of injury recovery!3 Full disclaimer: this aligns with my personal experience having dealt with an ACL injury and, therefore, fuels my own confirmation bias. The mental side of my recovery (e.g. anxiety of skating for the first time) has always been more challenging to overcome than the physical side (e.g. adding a few kilos to my front squat or deadlift).

Athletes recovering from an injury experience various psychosocial stresses like re-injury anxiety, feeling isolated, or pressure to return too early. Podlog et al. (2011)4 suggest that sports medicine practitioners address an athlete’s competence, relatedness, and autonomy to help facilitate successful RTS. Some interventions strategies are listed in the mini infographic below. The next time you see an athlete struggling with rehab, have a chat, listen, and maybe give one of these strategies a go!

The psychosocial train doesn’t stop there! Next town, RTS screening! We also should account for these psychosocial factors in our RTS battery. I mean, filling out questionnaires is everyone’s favourite pastime, right? We even have questionnaires developed specifically for ACL populations: the ACL-Return to Sport after Injury index (ACL-RSI) for psychological readiness to RTS (available as a mobile app!) and the ACL Quality of Life questionnaire (ACL QOL). These patient-reported outcome measures provide us with some nice numbers to examine but I would argue the best way to really assess psychosocial function is having open and honest conversations with your patient.

While we’re still on RTS screening, we probably have to come to terms with the idea that these criteria will never be able to predict who will suffer the dreaded second ACL injury. As Dr. Roald Bahr would say, the cause of (re-)injury is multifactorial.5 There are a multitude of intrinsic, extrinsic, modifiable, and non-modifiable risk factors at play. We would be hard pressed to find the perfect combination of RTS tests to predict re-injury in all ACL injured folks. That is, the RTS battery for recreational female skiers is probably going to look different for elite male footballers.

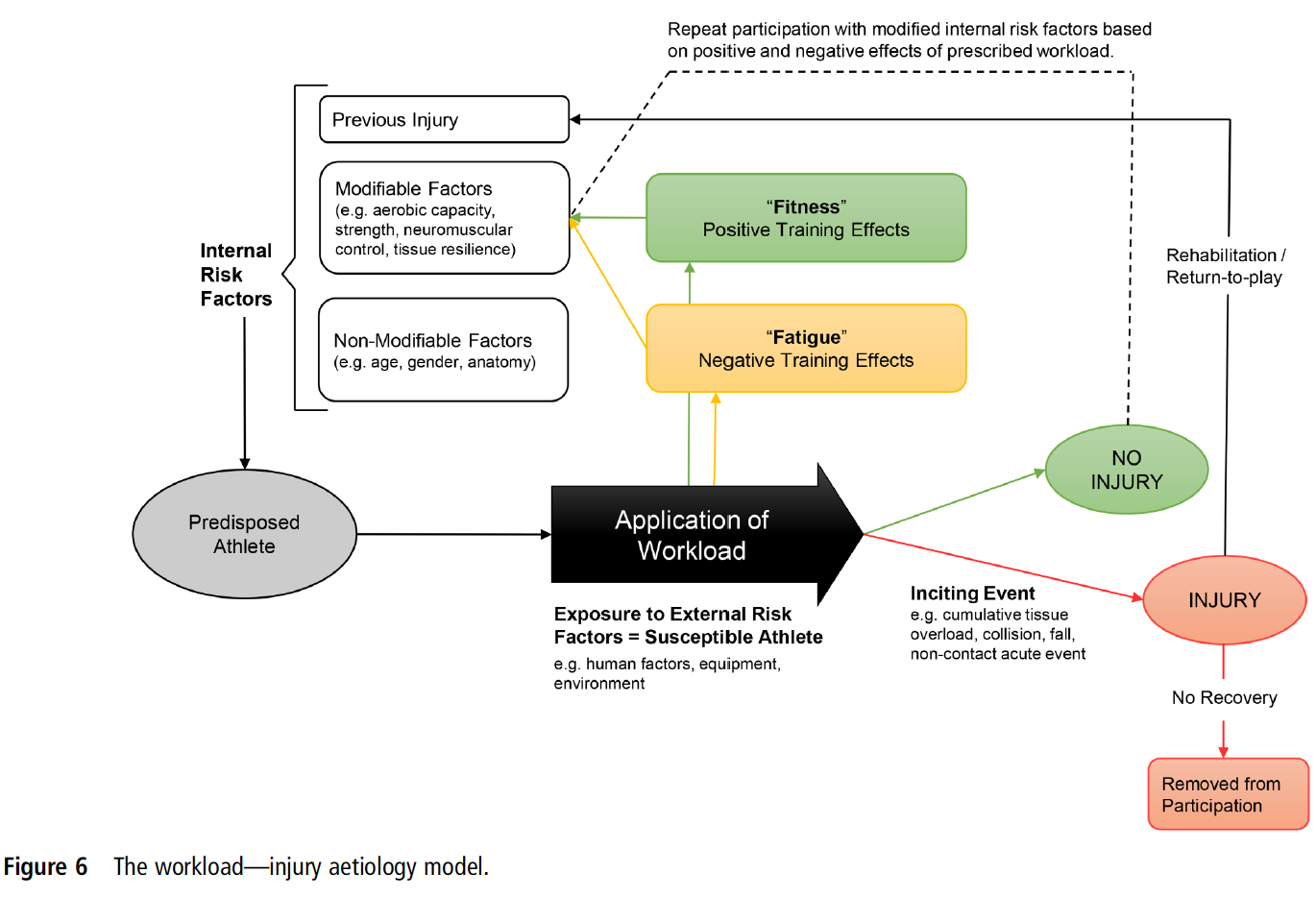

Alas, I really don’t want to be a Debbie Downer any more so let me share at least one thing all athletes returning to sport (and the medical team working with them) should consider: training and competition workload! There’s been some hype behind training load in recent years and Dr. Johann Windt has been right in the mix of it. Dr. Windt revised the dynamic, recursive injury aetiology model proposed by Meeuwisse et al. (2007)6 to include the positive or negative effects workloads can have on injury or re-injury risk.7 Proper training can lead to positive physiological adaptations (fitness) but poor training (e.g. spikes in training) can also induce negative adaptations (fatigue). Workload is the common thread for your recreational female skier and elite male footballer – something we should be aware of as we gradually return our athletes to the mountains or the pitch.

So what would Roald do (#WWRD, let’s get it trending, people) with your beloved RTS tests? I reckon he might tell us that performing some tests is better than no tests at all! RTS tests and workload monitoring won’t always tell us who is going to get injured again but they do tell us (and our athletes) if problems exist and can help guide our treatment plans. We shouldn’t throw away RTS screening completely but we need to understand its limitations.

The next time you have an athlete with an ACL in front of you, I challenge you to assess his/her psychosocial attributes just as often as you assess his/her physical attributes. Pull out a goniometer? Ask them how they think their recovery is progressing. Push against a handheld dynamometer? Figure out what movements they are scared or apprehensive about. Lay out a measuring tape? Check in to see if they’re feeling isolated or removed from their teammates or friends. For every ACL you treat, remember there’s a brain (prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and all) attached to it!

Curious to learn more about return to sport and injury screening from people with real knowledge (and not some stressed out PhD student)? Come to the Third World Congress of Sports Physical Therapy in Vancouver, Canada, this October to hear Dr. Clare Ardern, Dr. Johann Windt, and Dr. Roald Bahr drop some serious knowledge bombs on these topics and more!

Christina Le (@yegphysio) is a PhD candidate in Rehabilitation Sciences at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada. Her research interests include understanding health-related quality of life in youth who have suffered an acute knee injury and developing strategies to improve long-term quality of life. She also continues to work as a physical therapist at the Glen Sather Sports Medicine Clinic and is often found treating individuals with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries. Email: cyle21@gmail.com.

References

1. Webster KE, Feller JA. Expectations for return to preinjury sport before and after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(3):578-83.

2. Losciale JM, Zdeb RM, Ledbetter L, Reiman MP, Sell TC. The association between passing return-to-sport criteria and second anterior cruciate ligament injury risk: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018;49(2):43-54.

3. Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, Whitehead TS, Webster KE. Psychological Responses Matter in Returning to Preinjury Level of Sport After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(7):1549-58.

4. Podlog L, Dimmock J, Miller J. A review of return to sport concerns following injury rehabilitation: Practitioner strategies for enhancing recovery outcomes. Phys Ther Sport. 2011;12(1):36-42.

5. Bahr R. Why screening tests to predict injury do not work—and probably never will…: a critical review. Br J Sports Med. 2016.

6. Meeuwisse W, Tyreman H, Hagel B, Emery C. A dynamic model of etiology in sport injury: The recursive nature of risk and causation. Clin J Sport Med. 2007;17(3):215-9.

7. Windt J, Gabbett TJ. How do training and competition workloads relate to injury? The workload—injury aetiology model. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(5):428.