Undergraduate perspective on Sport & Exercise Medicine – a BJSM blog series

By Jimisayo Osinaike @jimisayoosh

Millions of football enthusiasts from all over the world either travelled to Russia or were glued to their television screens during the world cup, after all, it probably is the best entertainment football has to offer. However, for Sport and Exercise Medicine practitioners and enthusiasts, it also has presented time to reflect on injury prevention, player’s health and ultimately assess if we are truly winning when it comes to injury prevention in football.

Hamstring injury (HSI) prevention and rehabilitation has been at the forefront of football medicine discussion recently, with some sources stating it as the most common injury in football with a rising incidence [1]. Furthermore, it causes significant loss in playing time and the potential for abrupt career termination. In fact, the first injury sustained in the FIFA World Cup 2018 was a hamstring injury by Dzagoev, a Russian playmaker. This injury heavily limited his playing time at the world cup and was a big blow not just for him personally, but also for the host nation [2].

Studies exploring HSI prevention

Even though injury prevention in Sport Medicine is a herculean task due to the presence of many confounding risk variables, it is still necessary to deal with modifiable risk factors that may contribute to the injury. Increasing age, muscle strength imbalance particularly reduced eccentric strength of hamstrings and a previous HSI are established aetiologies [3-5].

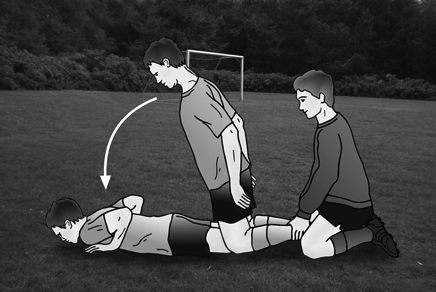

HSI can occur during the last swing phase when the hamstrings functions eccentrically (muscle lengthening) to decelerate knee extension, while also acting concentrically (shortening) to extend the hip joint. It is thought that during this rapid change from eccentric to concentric action that the hamstring are more susceptible to damage [6]. Thus, it has been suggested that increasing the eccentric strength of the hamstrings will enable the muscle to withstand the increased tension during the terminal swing phase of sprinting and invariably prevent HSI [7]. The Nordic Hamstring Exercise (NHE) is a form of eccentric exercise used to strengthen the hamstrings eccentrically. This exercise, addresses the mechanism of injury, and randomised controlled trials using the NHE have reported an encouraging reduction in HSI when compared to other forms of exercises such as the traditional concentric curls [8-10].

Weak compliance to NHE

Despite, the reach and overwhelming evidence in HSI reduction through NHE use, the adoption and implementation of NHE by elite football teams has not been universal. A retrospective survey amongst 50 elite football teams showed that compliance of NHE was poor and subsequently did not result in any significant reduction in HSI rate [11]. Though hamstring injury prevention was a priority amongst these teams, most of these teams adopted other exercise programmes other than NHE to prevent injuries. Moreover, some of the exercises adopted by these teams have not shown encouraging evidence to prevent HSI. Furthermore, another study looking at perceptions of injury prevention practices amongst elite football teams in nine countries, ranked NHE as fifth in the top five injury prevention exercises [12]. Thus, it is obvious that despite hamstring injury prevention should be a priority for both players and coaches, compliance is not encouraging.

Optimal NHE prescription

Possible reasons for this may be due to a paucity of evidence with regards to optimal prescription, namely the 1/ frequency, 2/ volume and 3/ timing of the exercise. Earlier trials on NHE intervention were conducted over a 10-week period during pre-season [8, 9]. However, the minimum effective dose needed to ensure efficacy and how it should be implemented during the competitive phase of the season remains unknown. Another major dilemma faced by players and coaches is whether to do NHE after the warm up session or after training. A study investigating the effect of fatigue on hamstring strength found out performing six sets of five repetitions of NHE after warm up resulted in greater eccentric hamstring strength decrements, which is likely to predispose the players to acute hamstring injury during training sessions [13]. Thus, it was suggested that NHE should be done after training or as a home-based exercise. However, will players be compliant?

It is time to consider evidence-based approaches to translate NHE and other proven injury prevention exercises into real life settings. More studies are required to provide further insight into the volume and scheduling of NHE. Finally, a paradigm shift in methodology from quantitative to qualitative methodology will generate subjective reflections into the practices of NHE amongst football teams and invariably may provide insights on how increased compliance may be accomplished.

***

Further reading:

https://blogs.bmj.com/bjsm/2018/05/01/does-the-nordic-hamstring-exercise-prevent-hamstring-injury/

Jimisayo Osinaikeis a graduate of Medicine from Olabisi Olabisi Onabanjo University, Nigeria. He has a keen passion in Sport and Exercise Medicine. He is a certified level 3 England Rugby Union Pre-hospital immediate care in sport. He is presently a Masters student in Sport and Exercise Medicine at Manchester Metropolitan University, UK.

Manroy Sahni(@manroysahni) is an Academic Foundation Year 1 Doctor in the West Midlands with a passion for SEM. He also co-coordinates the BJSM Undergraduate Perspective blog series.

Please send your blog feedback and ideas to: manroysahni@gmail.com

References

- Ekstrand, J., et al., Hamstring injuries have increased by 4% annually in men’s professional football, since 2001: A 13-year longitudinal analysis of the UEFA Elite Club injury study.British Journal of Sports Medicine, 2016. 50(12): p. 731-737.

- ESPN. Russian Allan Dzagoev likely to miss rest of World Cup- Club Doctor. 2018 [cited 2018 June 22nd]; Available from: http://www.espn.co.uk/football/russia/story/3526090/russias-alan-dzagoev-set-to-miss-rest-of-world-cup-with-hamstring-injury.

- Verrall, G.M., et al., Clinical risk factors for hamstring muscle strain injury: A prospective study with correlation of injury by magnetic resonance imaging.British Journal of Sports Medicine, 2001. 35(6): p. 435-439.

- Yamamoto, T., Relationship between hamstring strains and leg muscle strength. A follow- up study of collegiate track and field athletes.Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 1993. 33(2): p. 194-199.

- Engebretsen, A.H., et al., Intrinsic Risk Factors for Hamstring Injuries Among Male Soccer Players: A Prospective Cohort Study.The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 2010. 38(6): p. 1147-1153.

- Chumanov, E.S., B.C. Heiderscheit, and D.G. Thelen, The effect of speed and influence of individual muscles on hamstring mechanics during the swing phase of sprinting.Journal of Biomechanics, 2007. 40(16): p. 3555-3562.

- Stanton, P. and C. Purdam, Hamstring injuries in sprinting – The role of eccentric exercise.Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 1989. 10(9): p. 343-349.

- Mjølsnes, R., et al., A 10-week randomized trial comparing eccentric vs. concentric hamstring strength training in well-trained soccer players.Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, 2004. 14(5): p. 311-317.

- Askling, C., et al., Hamstring injury occurrence in elite soccer players after preseason strength training with eccentric overload.Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 2003. 13(4): p. 244-250.

- Petersen, J., et al., Preventive effect of eccentric training on acute hamstring injuries in Men’s soccer: A cluster-randomized controlled trial.American Journal of Sports Medicine, 2011. 39(11): p. 2296-2303.

- Bahr, R., et al., Evidence-based hamstring injury prevention is not adopted by the majority of Champions League or Norwegian Premier League football teams: The Nordic Hamstring survey.British Journal of Sports Medicine, 2015. 49(22): p. 1466-1471.

- McCall, A., et al., Risk factors, testing and preventative strategies for non-contact injuries in professional football: Current perceptions and practices of 44 teams from various premier leagues.British Journal of Sports Medicine, 2014. 48(18): p. 1352-1357.

- Lovell, R., et al., Acute neuromuscular and performance responses to Nordic hamstring exercises completed before or after football training.Journal of Sports Sciences, 2016. 34(24): p. 2286-2294.