Swiss Junior Doctors and Undergraduate Perspective on Sport and Exercise Medicine Blog Series

By David Eidenbenz,

with the contribution of Dr. Sandra Leal

Mountain sports such as hiking, trail running, or ski touring are becoming increasingly popular. Trail access is improving, allowing people to go to higher altitudes. For both moderate and sustained efforts, caution is necessary before venturing to high altitudes, especially for people with pre-existing chronic diseases.

Since not every country has a mountain medicine specialist, sport physicians may be increasingly confronted with questions such as: “May I go skiing at 3700m despite my history of heart attack?” In this blog, we review:

- The potential altitude-related problems of patients planning high altitude activities and;

- How to lead a careful assessment of the pre-existing diseases in a sports medicine setting.

Physiological changes

High altitude is defined as an altitude over 2500m, but physiological changes occurs from 1500m (1). The inspired partial oxygen pressure decreases exponentially with the increase in altitude and the decrease in arterial oxygen partial pressure reduce the oxygen supply for the tissues (2). A sympathetic activation with consequent higher energy needs, tachycardia, hyperventilation, pulmonary arteries vasoconstriction, cerebral arteries vasodilation and fluid retention are some of the physiological responses.

Common altitude related diseases

The main illnesses related to altitude are acute mountain sickness (AMS), high altitude pulmonary oedema (HAPE) and high altitude cerebral oedema (HACE) (3) (4).

The occurrence of AMS depends on the speed of ascent: a fast ascent increases the risk of suffering from AMS. This concerns people who are for example visiting the Machu Picchu, Peru (2430m), skiers taking the cable car to the Klein Matterhorn, Switzerland (3883m) or trekkers to the Everest Base Camp flying from Kathmandu to Lukla, Nepal (2860m). Situations involving a quick ascent may not allow a proper acclimatization. Hypothermia, dehydration and exhaustion are also components of altitude exposition with increased risk for frostbites.

How to prevent altitude related diseases?

Key components of pre-travel consultation include travel itinerary review with altitude reached each day, number of nights spent at high altitude (>3000m), rest days, medical support, medical history, medications and immunizations (5). Optimal acclimatization is a key point in altitude travels, allowing a physiological adaptation to altitude. If no universal rules about acclimatization exist, it is generally recommended, once the altitude of 2500-3000m is reached, not to go beyond 300-600m of difference of level between two nights of sleep, and to take a rest day every 3rd-4th day (3). Finally, the effort should be moderate, hydration enhanced, and ingestion of carbohydrate-rich food, promoted.

Who is at increased risk?

Despite adequate acclimatization, some people will not tolerate altitude exposure. It is currently not possible to predict who will suffer from altitude sickness or not. It depends on genetic and acquired dispositions (5,6). The acclimatization and standards precautions allow to reduce the risk of experiencing high altitude illnesses, except for people with severe altitude intolerance (7).

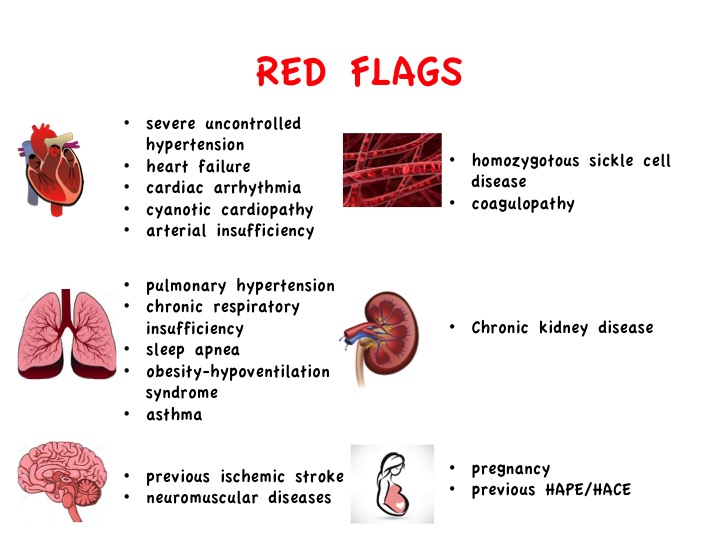

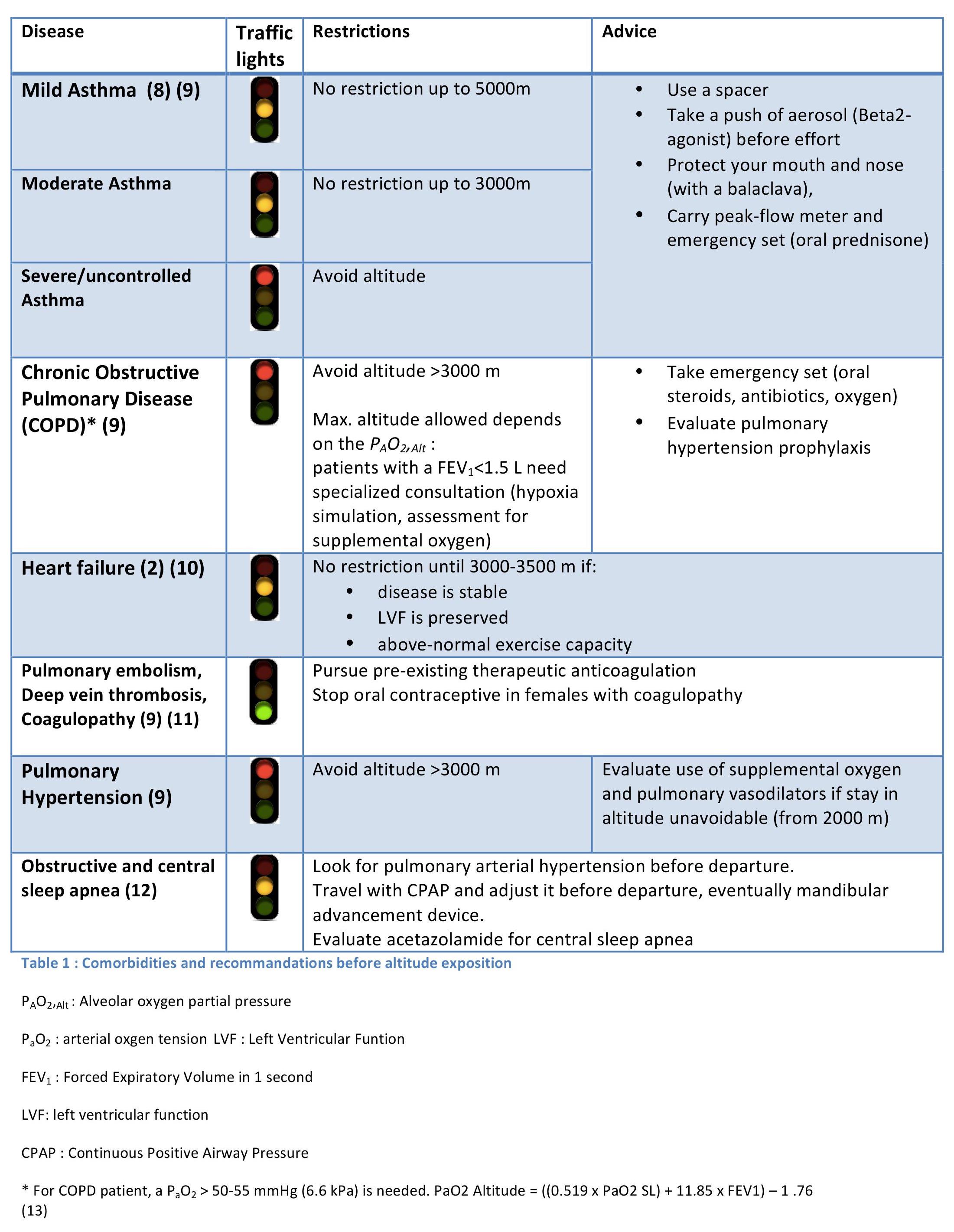

Regarding patients suffering from pre-existing chronic diseases, the Figure 1 proposes a non-exhaustive list of important comorbidities needing a particular look before departure. General recommendations for people with comorbidities are listed in Table 1.

Investigations

First of all, the functional capacity at sea level should be good.

- Routine laboratory tests and electrocardiogram are part of the normal check-up before traveling in high altitude.

- For people ≥ 50 years old and/or with history of cardiovascular events, it is recommended to add an ergometry and an echocardiography.

- The hypoxia altitude simulation test is available in some specialized centres: by asking the patient to breathe a mixture of gases (oxygen and nitrogen) with an oxygen saturation of 10.5 %, the test simulates the conditions encountered at the Mont Blanc altitude (4800 m).

- Patients with an oxygen saturation ≤ 92% at rest, and those with COPD and chronic hypercapnia under oxygen-therapy, should undertake a hypoxia altitude simulation test.

- Other specific tests should be evaluated according to the pre-existing diseases.

To answer our introducing question: a patient with history of heart attack with preserved LVF and a good physical condition is first allowed to go skiing up to 2500m. As myocardial oxygenation is sufficient after 3-4 days acclimatization, he will then be able to go at an altitude of 3700m.

In conclusion

- Go slow and acclimatize

- Have your disease under optimal control

- Evaluate your oxygen needs

- Pursue your usual medication and prepare an emergency set

- Be able to recognize and treat eventual altitude illnesses

****************

David Eidenbenz is a second year internal medicine resident based in Biel, Switzerland, and previously worked in an emergency medical service. He recently completed the “International Diploma in Mountain Medicine”. Email: daveiden7@gmail.com

Dr. S. Leal, SEM is a specialist and Master in Mountain Medicine

If you would like to contribute to the “Swiss Junior Doctors and Undergraduate Perspective on Sport and Exercice Medicine” Blog Series please email justin.carrard@gmail.com for further information.

References

- Imray C, Booth A, Wright A, Bradwell A. Acute altitude illnesses. BMJ. 15 août 2011;343:d4943.

- Dehnert C, Bärtsch P. Can Patients with Coronary Heart Disease Go to High Altitude? High Alt Med Biol. 1 oct 2010;11(3):183‑8.

- Hackett PH, Roach RC. High-Altitude Illness. N Engl J Med. 12 juill 2001;345(2):107‑14.

- Schoene RB. Illnesses at high altitude. Chest. août 2008;134(2):402‑16.

- Sanford C, McConnell A, Osborn J. The Pretravel Consultation. Am Fam Physician. 15 oct 2016;94(8):620‑7.

- MacInnis MJ, Lohse KR, Strong JK, Koehle MS. Is previous history a reliable predictor for acute mountain sickness susceptibility? A meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy. Br J Sports Med. janv 2015;49(2):69‑75.

- Richalet J-P, Lhuissier F-J, Larmignat P, Canouï-Poitrine F. Évaluation de la tolérance à l’hypoxie et susceptibilité aux pathologies de haute altitude. /data/revues/07651597/v30i6/S0765159715001847/ [Internet]. 22 nov 2015 [cité 26 févr 2017]; Disponible sur: http://www.em-consulte.com/en/article/1016514

- Seys SF, Daenen M, Dilissen E, Van Thienen R, Bullens DMA, Hespel P, et al. Effects of high altitude and cold air exposure on airway inflammation in patients with asthma. Thorax. oct 2013;68(10):906‑13.

- Luks AM, Swenson ER. Travel to high altitude with pre-existing lung disease. Eur Respir J. avr 2007;29(4):770‑92.

- Levine BD. Going High with Heart Disease: The Effect of High Altitude Exposure in Older Individuals and Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. High Alt Med Biol. juin 2015;16(2):89‑96.

- DeLoughery TG. Anticoagulation Considerations for Travel to High Altitude. High Alt Med Biol. 17 juill 2015;16(3):181‑5.

- Latshang TD, Bloch KE. How to treat patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome during an altitude sojourn. High Alt Med Biol. 2011;12(4):303‑7.

- Dillard TA, Berg BW, Rajagopal KR, Dooley JW, Mehm WJ. Hypoxemia during air travel in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med. 1 sept 1989;111(5):362‑7.