By Emily Ross (@EmilyRossPhysio)

Whoa…working in gymnastics, where do we start?

Gymnastics is a mesmerising sport which requires a level of power, flexibility, and not to mention a dedication and focus I have never previously witnessed in a childhood and adolescent age group. We are going to do a roundoff full twist through my top 5 tips from working in the world of gymnastics.

We will cover:

We will cover:

- What is needed in Acrobatic Gymnastics?

- .. Gymnastics and Rugby Union are basically the same?

- How a physio’s role in gymnastics can include risk assessment on acrobatic moves

- Why we must remember that gymnasts and rugby players are similar characters

- The role of a physiotherapist in a childhood and adolescent sport

Professionally I have had the opportunity to work with two very different sports; on one hand, Men’s Rugby Union, an open-skilled, dominated by male adults, contact sport with an 80 minute weekly peak in performance and on the other hand Acrobatic Gymnastics, a closed-skilled, female dominant population, aged pre and post maturation, who perform 2-3 minute routines just a handful of times across the competitive season. Now first things first, I have to admit I am not an ex-gymnast, although I am flattered when people ask; so the world of gymnastics was a brand new experience when I joined an Acrobatics Gymnastics Club 4 years ago.

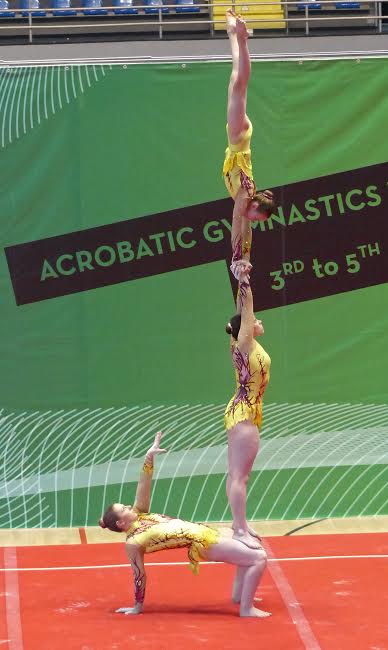

I highly recommend working in gymnastics. This sport presents exciting challenges as a medical professional, and the opportunity to work closely with gymnasts from their initial development stages, up to, career highlights of international competition. We have all recently enjoyed the Artistic and Rhythmic gymnastics disciplines at Rio 2016. If you’re wondering what Acrobatic Gymnastics is, then I would liken Acrobatic gymnastics to the floor element in Artistic gymnastics.

Here are my top five tips for working with gymnasts…

No.1: Spend time watching training, understanding the movement and strength requirements for gymnastics.

No.1: Spend time watching training, understanding the movement and strength requirements for gymnastics.

In acrobatics gymnastics, for the majority, gymnasts work in Pairs (Base and Top) or Trios (2 Bases and a Top), although you can also see a Men’s 4. If we take a Trio as an example; a Base will need to support the body weight of up to 2 gymnasts in both static and dynamic positions. The variety of partnerships and multidirectional nature means gymnastics is difficult to explain succinctly. You could describe Acrobatic Gymnastics as a sport of flexibility, strength and power throughout a multiple planes of movement [1].

The interesting medical challenge of gymnastics presents itself in the population of athletes you are working with. You are working with young female (predominantly in our club) athletes in a sport which combines non-modifiable intrinsic risk factors for injury; age, anatomical, hormonal, as well as the post-menarche neuromuscular control deficits, although the latter can be addressed [1-7]. Consider that these young athletes are required to hold load and complete movements in such outer ranges, which most fully developed adults would struggle to complete without issue, injury or long term effects. When I started at the club, it was eye-opening to find out that regular medical provision was relatively rare in club gymnastics.

No.2: Spend time with the coaches to appreciate the way movement is judged in competition.

The sports medicine discipline is a common skill-set needed to work in sport. However my experience in rugby, regarding power and movement efficiency in conditioning, needed to be built upon when I also started working in gymnastics. In rugby, as like many other sports, conditioning focuses on the action, be it sprinting efficiency to make that break away try, the power behind a tackle, a time efficient tumble turn in the pool, or serving an ace in tennis, the list goes on. There are many ways you could complete all of these, however usually coaches and the medical team would support an athlete to complete it in the most physically efficient and powerful manner, to produce the result successfully and safely without injury. Whereas in gymnastics, it is not just about the efficiency of an action, but the aesthetics of how gymnasts complete it, which was a new clinical consideration for me.

Gymnastics has a unique focus on specific limb alignments in scoring and deductions, where a limb may not be scored as ‘straight’ unless there is a degree of hyperextension at the knee or sufficient plantarflexion at the ankle. In rugby, I would aim to target excessive knee hyperextension on grounds of minimising joint translation, stress on the passive system and improving neuromuscular control of end range extension in basic tasks and progressing this into sport-specific loading drills. In gymnastics hyperextension is sought after; entering the world of gymnastics challenged my previous experience and understanding on sport-specific targets. For these reasons I believe No.2 is a relevant point for those transitioning from other sports as well as any new graduates joining the sports world.

No.3 : Consult with the coaches on safety screening acrobatic moves they selected in a routine.

I am proud to work in a club where the coaches’ main focus is long term health beyond gymnastics. Acrobatic gymnastics is not directly focused on efficiency of movement; it challenges the parameters of balance, joint range and motor control in each routine. I questioned what I could add to the club, as I have had no previous experience in gymnastics. Learning idiosyncrasies of the sport was accelerated from listening to coaches’ feedback on training; this can highlight where to aim any screening and prevention ideas. My role in gymnastics became clear when coaches asked about making gymnasts more flexible, more ‘fast-twitch’, or more powerful to throw higher. This is where my in experience rugby and sports medicine was truly complementary. I found building an inter-professional relationship with the coaches adds so much to a team and buy in is tenfold when they know you’re working towards joint goals, points mean prizes…literally.

The safety screening term developed from the coaches asking for my clinical opinion on gymnasts’ biomechanical risk/suitability for a move of higher acrobatic tariff (difficulty) or new routines when partnerships change. The coaches say this is one of the most valuable roles; particularly when they are pushing the boundaries of a gymnast’s capability with new elements. If you are venturing into gymnastics, clinically this is reassuring to be able to avoid putting a gymnast’s musculoskeletal system at more risk by adapting elements of a gymnast’s routine. Adaptations will occur either because anatomically they do not have the range or strength deficit in a certain range for an acrobatic element.

The safety screening term developed from the coaches asking for my clinical opinion on gymnasts’ biomechanical risk/suitability for a move of higher acrobatic tariff (difficulty) or new routines when partnerships change. The coaches say this is one of the most valuable roles; particularly when they are pushing the boundaries of a gymnast’s capability with new elements. If you are venturing into gymnastics, clinically this is reassuring to be able to avoid putting a gymnast’s musculoskeletal system at more risk by adapting elements of a gymnast’s routine. Adaptations will occur either because anatomically they do not have the range or strength deficit in a certain range for an acrobatic element.

Now this assessment is not fool proof, and I do not have hard-and-fast criteria. I understand the current discussion on movement analysis and other screening efficacy [8-11], maybe screening is the wrong term, but I would advocate the value of our clinical opinion to assist coaches in risk assessment. This allows the gymnasts to develop routines which they will be able to safely maintain, and I will implement a supplementary programme for that gymnast to aim at a higher tariff moves through the season. In fact this is where I came across my research idea to examine the neuromuscular control in young female gymnasts for my MSc, which I’m preparing for submission, but that is for another blog.

No.4: Pay attention to the potential to underreport symptoms.

I have identified many differences in rugby and gymnastics; after time, if you squint and tilt your head to the side, you realise as athletes, they’re hugely similar, yep, I did say similar! Both of these multidirectional-team sports demand incredibly strong athletes, who can regularly withstand an extraordinary load!

One of the fundamental reasons I work in rugby and gymnastics is that both athletes have this overt resilience, drive and committed mind-set. It is these characteristics, which will lead them to national and international levels but can also mask injuries. By comparison, weekly competitions in rugby, the drive for the players to make the next match is clear – I’ve found gymnastics is no different, and even harder at times in run up to competitions, as a gymnast cannot be as substituted out of a Trio, as easily as a rugby player in a 45-man rugby union side. Be careful that their enthusiasm to compete doesn’t overshadow the gymnasts’ communicating symptoms to you.

No.5: Build a rapport and communication with gymnasts’ of all ages is vital.

No.5: Build a rapport and communication with gymnasts’ of all ages is vital.

Working in a childhood and adolescent sport, you will meet gymnasts who may act with the professionalism of an adult, but they will only be 8 years old. Often gymnasts will never have been taught how to do basic S&C movement patterns, much as we don’t understand the Acrobatic specific terminology. We need to remember they are used to a different sporting-language, they may have not experienced an injury before, or know what an appropriate stretching sensation should be, or the difference between DOMs and a muscle tear. Certainly you will get some puzzled faces with Visual Analogue Scoring.

With symptom reporting in mind, I focused my first season at the club on communication rapport and educating the squad on what we called ‘good and bad pains’. This included teaching the gymnasts what physio can do to help them, why that will help in competitions, and what they can tell me regarding what they are feeling or concerned about.

I enjoy gymnastics because you are working with athletes who are developing in socially, physically, and mentally. Never underestimate gymnasts’ ability for information retention, but you must also not forget their ages. I feel we have a responsibility in their development, and I’m talking more than just physical performance. On reflection, so many times in the rugby world, I have run through players’ past medical history and hear stories of previous injuries as juniors that weren’t flagged, or investigated as you might have hoped, which leads to a frustrating unknown in baseline and query over initial prognosis of an injury.

Working in gymnastics we have an exciting opportunity to be the first medical professional to teach efficient loading strategies and movement patterns, to athletes new to non-sport specific conditioning. We have the responsibility to make sure they complete conditioning safely and efficiently for their developmental stage and anatomy, and the opportunity to further diminish the old school negativity around extreme gymnastic conditioning. We can help to start their athletic career with a professionalism (sports medicine hat on); from explaining strength and conditioning, the importance of communication, to highlighting the benefit of continuing other sports at school. I have found, this results in gymnast buy in, support from their parents and satisfied coaches’ by excelling in performance and long term resilience, which is pretty damn satisfying in the SEM WORLD.

Summary of advice!

- Spend time watching training, understanding the movement and strength requirements for gymnastics Rugby and gymnastics are more similar than you think…. Understand the resilience

- Spend time with the coaches to appreciate the way movement is judged in competition

- Consult on safety screening with the coaches on acrobatic moves selected in a routine and assess the risk/suitability

- Be careful that gymnasts’ enthusiasm to compete doesn’t overshadow their symptoms reporting.

- Building a rapport and communication with gymnasts’ of all ages, educating them to address sport with a sports medicine hat on.

- Never let rugby players in sparkly gymnastic leotards, there isn’t therapy for that.

Emily Ross is a Specialist MSK and Sports Physiotherapist with a special interest in Rugby Union and Acrobatic Gymnastics. She has been the Head of Medical Services at the Oxford School of Acrobatic Gymnastics for 4 years, she has worked at Harlequins RFC Academy and at Championship level rugby. She also works at the Centre of Health and Human Performance. You can follow her on Twitter (@EmilyRossPhysio)

References

[1] Deley, G, Cometti, C, Fatnassi, A, et al. Effects of combined electromyostimulation and gymnastics training in prepubertal girls. J Strength Cond Res 2011;25:520–526

[2] Hewett, T, Myer, G, Ford, K. et al. Biomechanical Measures of Neuromuscular Control and Valgus Loading of the Knee Predict Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Risk in Female Athletes: A Prospective Study. American Journal of Sports Medicine 2005;33:492-501. DOI: 10.1177/0363546504269591

[3] Lim, B-O, Lee, Y, Kim, J, et al. Effects of Sports Injury Prevention Training on the Biomechanical Risk Factors of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury in High School Female Basketball Players. American Journal of Sports Medicine 2009;37:1728-34. DOI: 10.1177/0363546509334220

[4] Myer, G, Ford, K, Palumbo, J, et al. Neuromuscular training improves performance and lower-extremity biomechanics in female athletes. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2005;19:51-60.

[5] Myer, G, Ford, K, Brent, J, et al. Differential neuromuscular training effects on ACL injury risk factors in “high-risk” versus “low-risk” athletes. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2007;8:39 DOI:10.1186/1471-2474-8-39

[6] Myer, G, Brent, J., Ford, K, et al. A pilot study to determine the effect of trunk and hip focused neuromuscular training on hip and knee isokinetic strength. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2008; 42:614-619. DOI: 10.116/bjsm.2007.046086

[7] Myer, G, Sugimoto, D, Thomas, S, et al. The influence of age on the effectiveness of neuromuscular traiing to reduce anterior cruciate ligament injury in female athletes: a meta-analysis. American Journal of Sports Medicine 2013;41:203 – 215.

[8] Clarsen, B, Berge, H. Screening is Dead! Long live Screening. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:769. DOI:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096475

[9] Hewett, TE. Response to ‘Why screening tests to predict injury do not work- and probably never will…a critical review’ Br J Sports Med Published online first: [07/07/16] 2016. DOI:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096388

[10] Moran, R, Schneiders, A, Major, K, et al. How reliable are functional movement screening scores? A systematic review of rater reliability. Br J Sports Med 2015. DOI:10.1136/bjsports-2015-094913

[11] Wright, A, Stern, B, Hegedus, E, et al. Potential limitations of the Functional movement screen: a clinical commentary. Br J Sports Med 2016 50:13 770-771 DOI:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095796