By Phil Clelland

Sport and Exercise Medicine: The UK trainee perspective – A BJSM blog series

This summer, I worked for British Exploring as the senior medic on their Project New Horizons expedition and provided medical cover for 67 participants during a three week trip to North West Iceland. This expedition aimed to inspire young people who are not in employment, education or training through adventurous physical activities including trekking and white water rafting.

My return to the UK and subsequent sports and exercise medicine (SEM) training, prompted me to reflect upon the crossover of skills, knowledge and behaviours between SEM and expedition medicine. This link is well documented in the sports medicine literature1, 2, 3 (and in a BJSM podcast with Dr Russell Hearn and BASEM today article featuring Dr Dan Roiz de Sa).

Below I build off this knowledge base, and reflect on my own experience to address the role of expedition medicine in sports and exercise medicine training.

The rise of expedition medicine

Expedition medicine has recently increased in prominence. This is in part due to the popularity of adventure travel/endurance events, the ease and affordability of international flights, and a plethora of fundraising treks and sustainable development projects.

The growth in demand has been met by a degree of formalisation in expedition medicine training. Multiple companies offer courses of varying length in a range of locations from the Brecon Beacons to Costa Rican jungles. A postgraduate diploma in expedition and wilderness medicine is now delivered by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow and doctors can seek fellowship accreditation through the Royal Geographical Society or the Academy of Wilderness Medicine.

Each expedition is different in terms of its objectives, size, location and level of organisation. However, my experiences over several trips suggest that each follows a similar format which lends itself well to coverage of aspects of the SEM curriculum.

Selection

Organisations require submission of a CV or application form and seek a broad medical background. Expedition practice typically includes emergency medicine, sports medicine, general practice, tropical medicine and pre-hospital care, thus qualifications in these areas are desirable. Personally, I’ve completed diplomas in tropical medicine and SEM as well as pre-hospital care and expedition medicine courses.

Subsequently, programs require a face to face meeting which can take the form of an interview or an assessment weekend. The latter is more intense and test’s the applicant’s ability to work effectively in a team, practice independently, manage emergency scenarios and cross an icy river in just their underwear whilst still smiling.

Pre-expedition planning and training

Pre-expedition planning and training draw the strongest parallels to an SEM team physician 4. These elements are as essential to a successful and safe expedition as to sporting event cover5. Similar responsibilities include:

- medical screening of participants,

- determining the necessary medical equipment to take, sourcing and transportation,

- advising on potential health issues,

- casualty evacuation planning,

- teaching first aid/preventative health

- developing nutritional strategies.

Risk assessment plays a large part and not at all mundane when the process involves snakes and machetes. Also essential, is ensuring adequate personal, professional indemnity.

On expedition

The doctor will often be part of a small advance party. This helps establish rudimentary medical facilities at a base camp, confirmation of evacuation plans, communication systems, adequate local medical facilities and more glamorous tasks such as digging a hole for the long drop toilet.

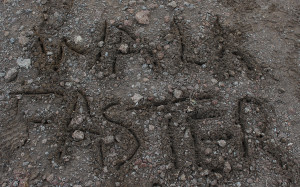

The main party’s arrival signals the start of the incredibly diverse clinical work. Geographical location, objectives of the expedition and demographics of the individuals all influence the scope of roles. Conditions encompass anything from medical emergencies to psychological problems but musculoskeletal complaints often predominate. Management of environmental related illness is also common. All of these can be complicated by occurring in challenging, isolated situations. Examining for corneal abrasions in a land of 24 hour sunlight requires some improvisation.

Training may also involve a research or audit project. The premise of many expeditions is personal development through adventurous, physical activities. Whilst in Iceland, I conducted a study using serial psychological assessments to determine the impact of these activities upon the participants, several of whom had pre-existing depression or anxiety. Much like in SEM, the quality and range of future research investigations will in part determine the progress of Expedition Medicine.

Post expedition

A doctor’s post expedition medical report includes critical incidents and detailing all significant medical issues. They also make governance and quality control recommendations based on reflective practice. Following my recent expedition, suggestions included mandatory pre-expedition dental checks, trauma and resuscitation training for leaders and emergency protocol flash cards in medical kits. Handover letters to GPs regarding major or on-going problems are also written to ensure continuity of care. These elements are all similar to an SEM practitioner.

So what are the benefits as part of SEM training?

The SEM trainee’s education may benefit by undertaking expedition work and their skillset lends itself perfectly to the role. It is a complementary experience to an already diverse and interesting career. Expedition Medicine frequently tests effective teamwork, leadership, managing uncertainty and professionalism. The co-ordination of a casualty evacuation that had fallen into a glacial river, fractured their scaphoid and developed hypothermia is one such example from this summer. Building the skills to respond to and manage this scenario effectively will strengthen anyone’s skills as a SEM practitioner.

To end on a personal note, expeditions have impacted me significantly. They have provided the same (albeit based in very different contexts) satisfaction, enjoyment, inspiration and memories as working at sporting events. Playing a small part in helping others achieve their goals and witnessing the resulting personal development is very rewarding.

********************************************************

Phil Clelland is an ST3 in Sports and Exercise Medicine in the North West Deanery. He has a background in hospital medicine and general practice. He enjoys all sports but has an interest in endurance and adventure sports and completed his first ultra-marathon this year. He plans to raise money to support future British Exploring expeditions by racing a dug-out sailing canoe along the coast of Zanzibar next summer.

References

- Heggie TW. Paediatric and adolescent sport injury in the wilderness. Br J Sports Med 2010;44:50-55

- Buckler DGW, O’Higgins F. Medical provision and usage for the 1999 Everest marathon. Br J Sports Med 2000;34:205-209

- Maruff P, Snyder P, McStephen M, et al. Cognitive deterioration associated with an expedition in an extreme desert environment. Br J Sports Med 2006;40:556-560

- Brukner P. Surviving 30 years on the road as a team physician. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:610

- Tillett E, Loosemore M. Setting standards for the prevention and management of travellers’ diarrhoea in elite athletes: an audit of one team during the Youth Commonwealth Games in India. Br J Sports Med 2009;43:1045-1048