John Orchard, BJSM guest blog (@DrJohnOrchard)

Another major football tournament is on – Euro 2012 – and those following the England team keep reading (yet again) about the number of injured players. Why do injuries seem to be more prevalent than ever if our professionalism is supposedly improving?

In trying to answer this question, why not start with elephant in the room? The players are expected to play too much football, with not enough time for recovery. The marketing and finance gurus, who seem to be charge of scheduling games and tournaments without much input from a sports science and medicine perspective, don’t seem to have much sympathy for multimillion pound players, as long as there are enough of them to replace those who fall by the wayside due to injury. The club managers, who can face the sack if their teams don’t win enough games, also don’t have much sympathy for the national team managers, who are under exactly the same pressure, and vice versa. It apparently is on the agenda to try to reduce the number of games that a top player is expected to participate in annually, but it is tough to find a solution when clubs have so many important competitions and the national teams also want to use their best players at every opportunity.

So if you are a sports medicine professional working for one of the clubs or countries, do you just throw your hands in the air and declare that due to forces beyond your control there is little you can do about your club/country’s injury crisis?

There are a few experts around who believe that sports science & medicine staff should take matters more into their own hands and exert more pressure on managers to load players less at training and give them more time off with rotation, which (as common sense and science would dictate) would hopefully lead to lower injury rates. One of the most outspoken experts is Raymond Verheijen, who has publicly castigated medical and fitness teams for not doing enough to balance match and training loads in players1. Many other sports medicine and science experts in the football world would partially agree with his views (that footballers train too hard and play too often) but would deny his assertion that individual practitioners have the power to easily change these factors.

Is there a plausible explanation as to why the majority of teams might be pursuing a strategy of training players too much and failing to rotate their teams enough? An examination of the culture within football might provide an answer. One of the universal aspects of the “football culture” is that the manager is all-powerful and virtually-all-accountable. Part of the “all-powerful” bit means that if there is a dispute between the manager and a doctor, physio or conditioner that the manager can pull rank and resolve the dispute in his favour. It is tempting to also suggest that the manager is “fully accountable” for results and in most cases this is true (i.e. if he doesn’t win enough games he often will face the sack). In the face of results which seem unacceptable (i.e. most of the time to fans and media with optimistic expectations), the manager usually has very few “get out of jail” cards. Perhaps one of the few he does have to regularly fall back on is that “too many of our top players were injured and hence we didn’t get the results we would have expected”. This one possibly will wash to an extent with the board and the fans, as there is still a common view that injuries are generally random and therefore out of a manager’s control. This may explain a paradox in the way that managers manage. Although you would expect a rational manager to try to avoid injuries where possible (which would improve team performance), by doing so he might sacrificing a valuable “get out of jail” card. To illustrate further, on reading that Manchester United had many injuries2 in season 2011-12, do you think that the public reputation of Sir Alex Ferguson is more enhanced (that he almost won the league despite a horrendous injury toll) or diminished (that he oversaw a regime where too many injuries occurred)? My guess is the former.

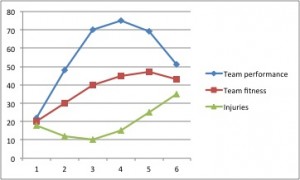

Let’s take a few hypothetical (but close to reality) graphs of the relationship between training load on the x-axis and player fitness, team injury rate and team performance (fitness minus injury rate) on the y-axis (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Relationship of training loads (‘x’ axis) to team fitness, performance and injuries (‘y’ axis)

The science and our experience would tend to agree with the general shapes of these curves, although it is impossible to put actual numbers on the data points in real life. Also, it goes without saying that loading is far more complicated (types of training, length, intensity, rest periods, injury layoffs, cycling etc) than a simple linear x-axis. However, please bear with the reduction of all the complexity to a simple x-axis for the sake of this hypothetical. With respect to the red curve (‘team fitness’), it is true that to a point, the harder you train the fitter you will become, although at some stage, e.g. zone 6 on the x-axis, overtraining will kick in and further training will actually be detrimental to fitness. With respect to the green curve (‘injury rate’), if you are unfit you will get a lot of injuries but if athletes train too hard3-6 (or play too much7 or often8) they will also get more injuries when compared to more moderate training regimes. If team performance (blue curve) is a combination of fitness minus injuries9, then in theory the best zone for overall team performance might be zone 4 on the graph. However, for a manager operating in the ‘real world’, where he may be sacked if his team loses games and he can’t come up with an acceptable excuse, zone 5 may be a preferable target, even if it means a detrimental performance compared to zone 4.

If you are a team doctor or physiotherapist, your KPI (“key performance indicator” in business jargon) should theoretically relate to the green curve on the graph (injuries) and you might even be more comfortable with a training load in zone 3, which could put you at odds with the manager who prefers zone 5. Again, it is worth emphasising that in the real world, a good medico would not tend to suggest a blanket reduction of all training, but would look at individual risks for injury and try to set specific training limits for those players most at risk of becoming injury or worsening a pre-existing injury. From a coaching perspective, the perception of this professional approach may still be that it is an attempt at blanket load reduction (as in “the medical staff want to stop me from training/selecting my players as much as I’d like”). How much a staff member wants to try to butt heads with someone who has ultimate power to hire-and-fire may determine how much the issue gets pressed about lowering the training loads of certain players (or rotating the players more often in matches). It certainly doesn’t make you feel any bolder if you hear about some of the high profile EPL team medical staff members who have left their clubs recently, perhaps for standing their ground to the manager about trying to prevent injuries, when maybe those who have yielded more easily still survive to tell the tale. On the topic of the ‘real world’, medical staff often have the sneaking suspicion that the only KPI that matters is keeping in the good books of the manager and doing basically whatever he dictates.

I understand the need to make managers accountable, but also feel that the power base between the managers and medical staff at football clubs is slanted far too much in the managers’ favour9. In one sense, I partially agree with the criticisms of Verheijen, but on the other hand I can see why there needs to be a major culture shift before individuals at football teams can institute much of a change. That is, it is not necessarily the fault of the medical staff that they don’t have enough influence at football clubs.

Until the culture can be shifted, perhaps high injury rates may be relatively inevitable in most football teams, both at club and national level.

References

- Veysey, W. Amateurish & prehistoric: Russia coach Verheijen slams England’s Euro 2012 preparations.

- Miller, A. Manchester City top the ‘injury league’, with Manchester United bottom.

- Gabbett TJ, Ullah S. Relationship between running loads and soft-tissue injury in elite team sport athletes. J Strength Cond Res 2012 Apr;26(4):953-60.

- Gabbett TJ, Jenkins DG. Relationship between training load and injury in professional rugby league players. J Sci Med Sport 2011 May;14(3):204-9.

- Gabbett TJ. The development and application of an injury prediction model for noncontact, soft-tissue injuries in elite collision sport athletes. J Strength Cond Res 2010 Oct;24(10):2593-603.

- Orchard J. Understanding some of the risks for soft tissue inury–a Malcolm Blight legacy? J Sci Med Sport. 2002 Jun;5(2):v-vii.

- Orchard JW, James T, Portus M, Kountouris A, Dennis R. Fast bowlers in cricket demonstrate up to 3- to 4-week delay between high workloads and increased risk of injury. Am J Sports Med 2009 Jun;37(6):1186-92

- Dupont G, Nedelec M, McCall A, McCormack D, Berthoin S, Wisløff U. Effect of 2 soccer matches in a week on physical performance and injury rate. Am J Sports Med 2010 Sep;38(9):1752-8.

- Orchard JW. On the value of team medical staff: can the “Moneyball” approach be applied to injuries in professional football? Br J Sports Med 2009 Dec;43(13):963-5. (Free Online)

John Orchard is an Australian sports physician who has worked with numerous professional team sports, but none in the EPL — for that league he is only an armchair expert. His sometimes controversial views are personal and not necessarily representative of organisations he is affiliated with. You can read more at www.johnorchard.com and/or follow @DrJohnOrchard on Twitter

——————

The beauty of social media….(4 hours after the original blog post)

A reader just alerted us to Jan Ekstrand’s paper supporting the hypothetical graph above with data. We’d be breaking copyright to post the PDF so we can’t do that but you can read the abstract here on PubMed.