Zeina Daccache, a Lebanese film maker, discusses her strategic reform campaign in Lebanese prisons and lobbying for other disadvantaged populations

Interview by Khalid Ali, film, and media correspondent

Zeina Daccache has been advocating for marginalized groups in Lebanese prisons since 2006. Her calling followed the realisation that ‘mainstream theatre’ excludes and marginalises further society’s outcasts. She reminisces on how her model of ‘theatre activism’ developed: ‘’I began this work as a result of a feeling of boredom as a theatre artist: I was bored of the vicious, incestuous and sterile cycle of theatre, where colleagues attend each other’s shows, all dealing with well-known texts written by well-known playwrights, and having no connection to reality or to everyday life’s stories. I began to question theatre artists and ask myself: Why have we isolated ourselves? Why are we performing only in front of the ‘educated’ while losing sight of a large section of our society? Where are the people who want to communicate something of vital importance to the audience? What about the immigrants we encounter daily in Beirut streets, the addicts residing in rehabilitation centres? What about mentally ill patients forgotten in hospitals or the 7000 inmates crammed inside Lebanon’s overcrowded prisons? I started to wonder if the artists on stage would come from the people who have something worthwhile to say, and motivated to put their hearts and souls into making change happen’’.

Restoring the balance of “whose voice is worthy of telling which stories,” Daccache comments further: ‘’I was also closely observing the way in which advocacy for certain populations’ needs and rights was conducted in Lebanon. I realized that it has always been accomplished via institutions or professional activists: we hear members of the Parliament or lobbying groups speaking up for prisoners’ rights or see a nongovernmental organisation leading a campaign to stop domestic violence; but we never hear the message coming directly from the affected population. So, in 2006, I decided to see how theatre and drama therapy can live and grow in the most forgotten of places and in the most difficult situations. I felt that performances would need to be constructed from the actors’ own words, stories, experiences, reflections, hopes, dreams, and that by incorporating these lived experiences into plays, the performances could lead to real change.”

Believing in the power of authenticity, Daccache adds: ‘’I was confident that a performance enacted by prisoners in front of society at large (and not just played for an ‘educated elitist’ audience) could challenge the status-quo in them, in the society, and ultimately, in the policies used against them. I felt that through their art they could self-advocate, and thereby communicate their message to the decision-makers; this time, however, using a constructive means – the artistic product – instead of a joining a disruptive riot or through appearing in a cheesy TV report.’’

In 2007 Daccache was a pioneer in organising the first drama therapy project in the largest detention centre for men in Lebanon: Roumieh Prison, which accommodates 3500 inmates in buildings that were originally built for a maximum of 1000. The establishment of a drama therapy and theatre program inside Roumieh (or indeed inside any Lebanese prison) was an unprecedented act. Art, drama, or music were thought of as ‘luxury commodities’ not to be consumed by convicted prisoners. While working with inmates, Daccache assumes several roles: a therapist, an activist, a human rights lawyer, a policewoman enforcing order, but perhaps above all a sister and a trusted friend.

In 2007 Daccache went on to establish the Catharsis-Lebanese Center for Drama Therapy, the 1st non-profit organization in Lebanon to promote and offer therapeutic actions using theatre and art for individuals and groups in various social, educational and therapeutic settings such as substance abuse treatment centres, mental health facilities, hospitals, correctional facilities, private practice settings for children and adults, schools, and corporations (1).

Catharsis produced the play and documentary film 12 Angry Lebanese with male inmates of Roumieh Prison (2009-2010), an adaptation of Reginald Rose play 12 Angry men. Members of the jury in the play were performed by the inmates in an intentional reversal of roles. Roumieh represents a microcosm of Lebanon and its sectarian groups. The play was presented in front of an audience of 2000 people over 2 months. Several performances were attended by public audience including family members of the inmates, and decision makers from Ministers, MPs, and Chiefs of Internal Security.

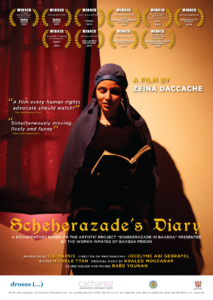

Engaging with residents of several institutions, Daccache continued her mission with Scheherazade in Baabda, a play with Baabda prison women inmates (2012); From the Bottom of my Brain, a play with the residents at Al Fanar psychiatric hospital (2013)’ and Johar… up in the Air, a play portraying stories of inmates suffering from mental illness in Roumieh Prison (2016).

Daccache’s latest film The Blue Inmates set in Roumieh prison has been selected to participate in the ‘Final Cut’ section in the 77th Venice Film Festival. The film is a documentation of the process of making the play Johar … up in the air (trailer).

Daccache’s portfolio of theatre productions and films resulted in several examples of law reform

12 Angry Lebanese succeeded in persuading the government, through advocacy by several decision makers attending the play, to start implementing in 2009 Law number 463 of the penal code for the reduction of sentences. That law had passed in 2002 but had never been implemented. Prisoners today can apply for a reduction of their sentences based on good behaviour.

In April 2014, after years of activism against domestic violence, a bill for the protection of women and members of the family was passed in the Lebanese Parliament. The documentary Scheherazade’s Diary was part of the campaign to change the law.

Daccache’s Shebaik Lebaik play lobbied actively against a law which prohibited migrant domestic workers from having romantic relationships on Lebanese territory. In an act supported by decision makers from the Ministry of Justice, who attended the play, the discriminatory law was abolished in 2015.

Johar… Up in the Air performed by Roumieh Prison inmates lobbied for changing articles 231 to 234 in the penal code which stipulated that incarcerated mentally ill offenders should stay in a special psychiatry unit in prison until an appointed tribunal decides to end such incarceration after evidence of “cure,” which in reality means that these subjects are destined for a life sentence. Two draft laws calling for a fair Legislation for mentally ill Inmates and inmates sentenced for life, prepared by Catharsis, have been submitted to the Lebanese Parliament in 2016 after being signed by 7 MPs from different political parties in collaboration with the EU.

![Zeina Daccache [far right] at the rehearsals for Johar.... Up in the Air](https://blogs.bmj.com/medical-humanities/files/2020/09/johar-300x276.png)

By portraying stories of inmates, some of whom are mentally ill, or women who suffered gender-based violence, and engaging them in drama, music, and dance, Daccache argues that personal and societal reform is possible. Their stories portray a journey of understanding through reflection, transformation, evolution, and hope. Participants in the drama therapy sessions, plays, and documentaries have connected with their humanity having been treated by Daccache and her team as human beings who can contribute to society through creative art. They have discovered their self-worth, challenged society’s rejection, and asserted their new identity as champions of change.