Reflection by Clare Best

Risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy, December 2006.

We have breast cancer in the family, on my mother’s side. While I was starting to think about whether to have preventive surgery, my cousin developed multiple aggressive tumours. This meant that in two generations of women I was the only one who had not yet developed breast cancer. I took action. It was one of the best things I’ve ever done, or will ever do. The surgery steered me away from a strong likelihood of developing a particularly deadly form of genetic breast cancer.

After a few days in hospital, I was sent home – relieved, even euphoric, to be flat-chested. At night, I used to lie awake on my back, processing the emotional and physical impacts of the surgery. It was hard work keeping up with myself, my changed body, and the thoughts that raced through my head in the small hours. But mostly, I reckoned I was doing fine. You’re coping really well, everyone said.

But I soon realised there was something I wasn’t coping with at all: numbness. Extensive numbness – right across my torso, up to my neck, down to my navel, under my arms, along my inner arms, sometimes as far as my wrists and hands. With my eyes closed, I let my fingertips explore the skin beyond the dressings that covered two nine-inch wounds on my chest. I had read that it is important to reconnect with the post-operative body through regular touch, that this supports the healing process. But really, I was trying to find out if the parts of me I was touching could feel anything at all. They couldn’t. But I couldn’t stop testing. I was caught in a vortex of numbness.

Until then, I’d never really thought about the discomforts of non-feeling.

I’d been warned there would likely be ‘numb patches’ after the surgery, and the surgeon explained these should gradually regain feeling over the weeks and months following the operation. I accepted this, and was ready to be patient. But no-one had suggested the post-surgery numbness would be so widespread, so deep, so strange – as though other parts of myself, as well as my breasts, were missing altogether. I worried that I didn’t know how to relate to the numb parts. Were they frozen? Dying? Already dead? Would the deadness spread? Would I ever feel like myself again? How should I think about the parts of me I knew were there, but which lacked sensation? And why did the numbness make me feel so edgy, confused, restless, and panicky?

The answer to those questions came early on a dark January morning, in a rush of light in my head – I think of it as a visit from an angel. For a minute or two I seemed to be gathered up into a cloud or a capsule of knowing. My fingers tingled, my body buzzed, while my mind was as calm and glassy as a lake in summer. Then thoughts arrived: I had long had a sense that there were parts of my memory and psyche to which I had no access. I both knew and didn’t know that these numb areas were associated with things that had happened to me as a child, abusive things. I had lived with this kind of numbness most of my life. I also knew, in this brightly-lit moment, that now the numbness was manifested in my body and had been brought to consciousness, I couldn’t bear it any longer. The angel’s visit, sudden and fierce, let me understand that I must interrogate the numbness. And that this was something not to be feared, but to be embraced. This is your work, the angel said.

Some months after my surgery, when I was strong enough, I found a psychotherapist, who was actually another angel. We agreed to walk together on the long path to uncovering and understanding the abuse in my childhood – sexual abuse inflicted by my father – and the problems this had caused me, numbness being one of them. For ten years I worked with that brilliant angel-therapist, and I continue now, on my own – sometimes hearing her voice, as though we are still meeting. The work has given me back my life.

When I was a child, my body wasn’t mine. My father annexed my body and so he annexed me. If our bodies are mapped onto our minds, then our minds are also mapped onto our bodies. Parts of me became inaccessible. Numb. Having diminished power of sensation or motion: powerless to feel or act: stupefied: causing or of the nature of numbness (Chambers English Dictionary). My numb areas were physical, emotional and psychological.

As my therapy progressed, the exploration of my numbness released the pain in my body as well as the pain in my emotions and psyche. Mysterious symptoms that had plagued me all my life – the results of suppressed memories – queued up for attention along with more recent pains and wounds which I had also pushed under (such responses become habitual). Sometimes this was alarming: childhood stomach cramps recurred, I suffered neck pain and lower back pain, cystitis came and went, headaches and distortions of vision returned, parts of me developed temporary twitches and tics. And there were tears, week after week.

More than four decades had passed since the abuse, and now it was as though painful sensations were invading my life. Their arrival often accompanied specific memories, but sometimes the painful sensations were the memories, and I learned to accept them as such, and honour them, by feeling them fully for the first time. All these woundings had been tucked away in me, as though they were in the deep freeze. To set myself free, I had to take them out, unfreeze them, see what they were. Then put them aside. As I did this, I gradually reinhabited myself. I came home.

Thirteen years after the surgery, and more than twelve since embarking on psychotherapy. I still have some numb patches in my body, in my head and emotions, in my memory. But they are many fewer and they are much less severe than they were. And anyway, numbness no longer makes me anxious. I accept and love myself as I am – body, mind, emotions, wounds. The known, the unknown, the unknowable.

And let me tell you, I regularly meet and talk with angels.

Clare Best is a writer, poet and collaborative artist. She has published five volumes of poetry, the most recent of which is Each Other (Waterloo Press 2019). Her multimedia project Breastless, inspired by experiences of family breast cancer and risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy, can be accessed on the Life Writing Projects website of the University of Sussex: https://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/lifewritingprojects/body/breastless-encounters-with-risk-reducing-surgery-by-clare-best/.

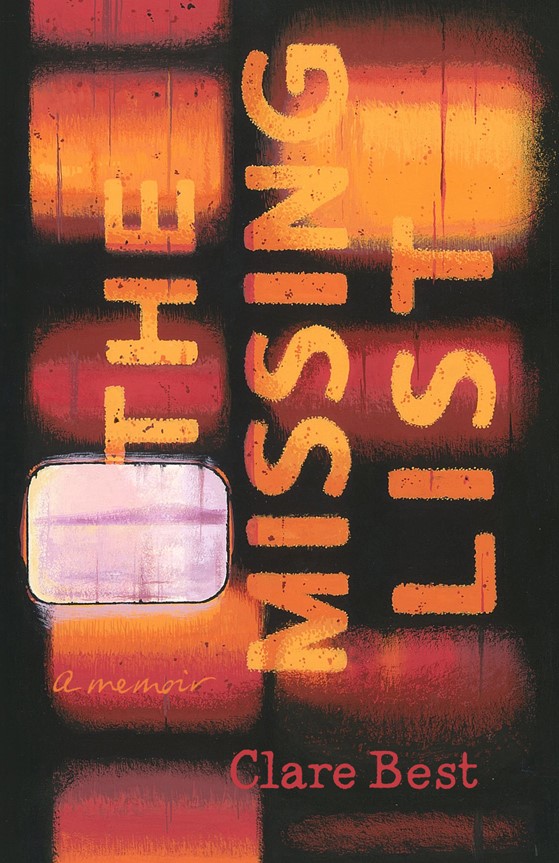

Best’s prose memoir The Missing List (Linen Press 2018) attempts to understand and explore her relationship with her father, his abuse, and her traumatic childhood.