Tell us more about yourself and the author team.

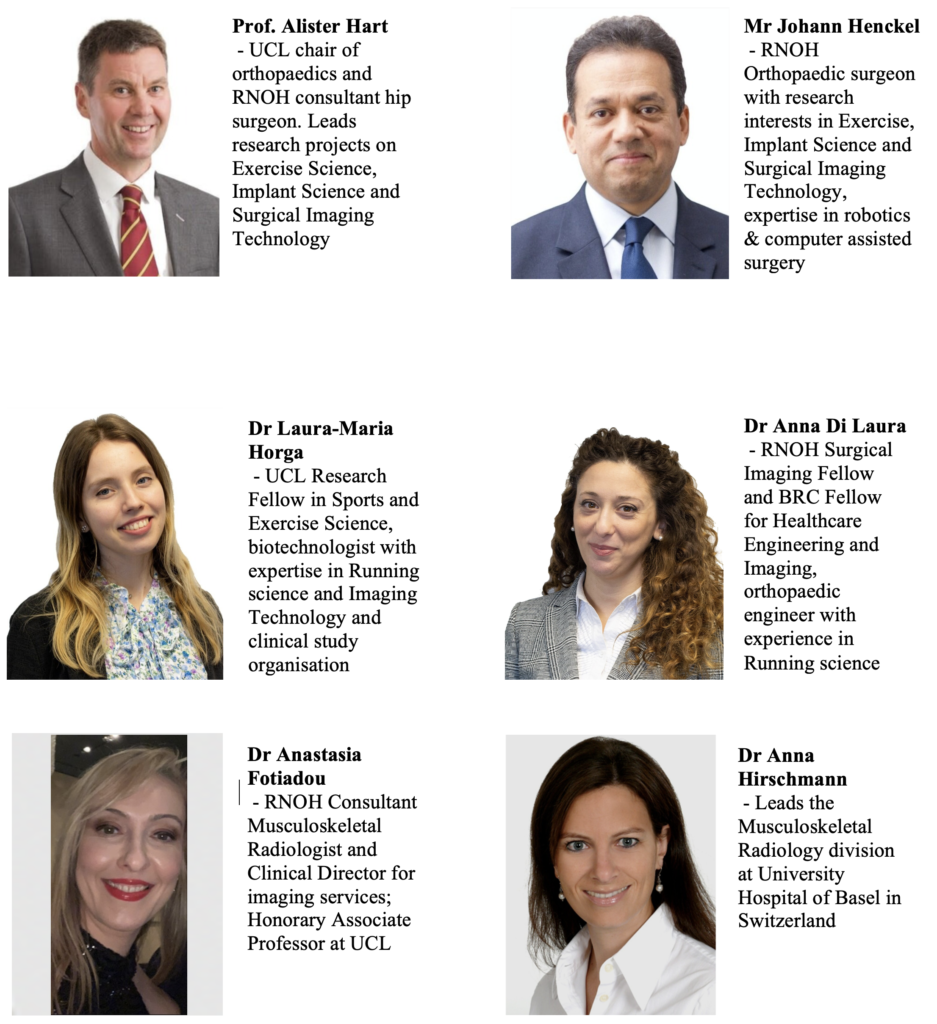

We are a research team of orthopaedic surgeons, biotechnologists, radiologists and engineers, at University College London, the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital and the University Hospital of Basel. This study is part of a medical project called Exercise for Science, aiming to better understand the effects of physical exercise on the human body through medical image analysis. We are passionate about health science and technology and are investigating the optimal dose of exercise to promote good health, maximise benefits while preventing injuries.

Here are some links through which you can follow us:

- Website: www.exerciseforscience.org

- Instagram: exerciseforscience

- Twitter: @Running4Science (Exercise For Science)

- Linkedin: Exercise for Science; Laura Maria Horga

What is the story behind your study?

Prof Alister Hart (PI of this study) is an orthopaedic surgeon and keen runner who started this project due to his interest in the actual effects of long-distance running on the joints. Despite the increasing popularity of running and its anecdotal association with injuries, we realised that there is very little scientific evidence on this topic. This is why we decided to design studies using highly reliable imaging tools (3 Tesla MRI) to detect what is happening inside the body after long runs.

This current study builds on the success of one of our first studies focused on the knees of first-time marathon runners, done in collaboration with Virgin Money London Marathon, which was published in the same journal (BMJ Open SEM) and received media attention from NYTimes, The Times, The Telegraph. We expected to see damage in the knees of runners. However, we actually detected the opposite. The results showed that long-distance running did not damage the knees of runners and may even rebuild them, including those joints that were previously showing early signs of damage.

Having had this experience, we then organised another study analysing the hips of runners this time, and also including not only moderately active runners but also ultrarunners and individuals undertaking various amounts of physical activity. This is the first study of its kind.

The main idea is simple – take groups of people of different running ability levels and non-runners, and do MRI scans of their hips to compare their findings and monitor changes in symptoms.

In your own words, what did you find?

We found that the outcomes were similar in non-runners in comparison to moderately active runners and highly active runners, thus suggesting that people undertaking long lengths of running such as marathons and ultramarathons have no worse findings than those who run shorter distances or those who do not run.

What was the main challenge you faced in your study?

Recruitment, in general, may be challenging when having specific study eligibility criteria. We had to select only people meeting our inclusion criteria and eliminate certain confounders which may add bias to the study (e.g. other health conditions, illnesses, previous serious injuries). Also, an imaging study at this scale – of both hips of 52 runners (104 hip MRIs), using cutting edge technology 3 Tesla from The London Clinic – is quite expensive. Therefore we had to manage our resources carefully when planning the study.

If there is one take-home message from your study, what would that be?

Based on current evidence, long-distance running does not appear to add damage to runners’ hips, with no history of known injuries. This suggests that running may not be as bad as people presume it can be, according to popular misconceptions, and may better inform people on this when making exercise choices.