The world is battling with COVID-19 and each country is embracing shared but distinct strategies. COVID-19 presents additional challenge in low- and middle-income countries like Nepal, where the health system is often not adequately prepared to manage the epidemic. Facilities for hand washing and infection prevention at health facilities are minimum requirements and are paramount during the epidemic. In contrary, in a survey of health facilities in Nepal in 2015, it was found that only 58 percent had soap, 49 percent had running water, only one in five had medical masks and less than 10 percent had gowns (1). Availability of critical care services is even worse with just one ventilator per 114,000 population (2).This indicates that facilities’ readiness to provide services even under routine conditions is sub-optimal. Therefore, the perennial shortage of essential personal protective equipment (PPE), and limited capacity of testing services further strained the COVID-19 response in Nepal.

Realizing such shortcomings, the crucial strategy adopted by Government of Nepal (GoN) was to enforce the nationwide lockdown and restrict travel within and out of the country to disrupt the transmission (3). While the nationwide lockdown allowed some time to expand the COVID-19 testing services and physical distancing but achieving longer-term containment of the epidemic and post-epidemic response requires strong community engagement and localized response (4).

GoN adopted the 6T strategy (travel restriction, testing, tracing, tracking, treatment and together) (5). Local government has been active in implementing 6T strategies through risk communication, enforcing the lockdown, isolating the suspected cases, and arranging quarantine measures (5). After the federalism, per the constitutional mandate, three tiers of government were formed following the election of 2017. Local government is entitled the responsibility of delivering basic health services (6). These relatively new government structures are adopting various strategies to contain the epidemic. One of their most prominent roles has been creating a profile of migrants and identifying the need for self-quarantine and arranging quarantine services. Further, in coordination with the federal and provincial governments, local governments rapidly scaled-up the testing services and strengthened the contact tracing.

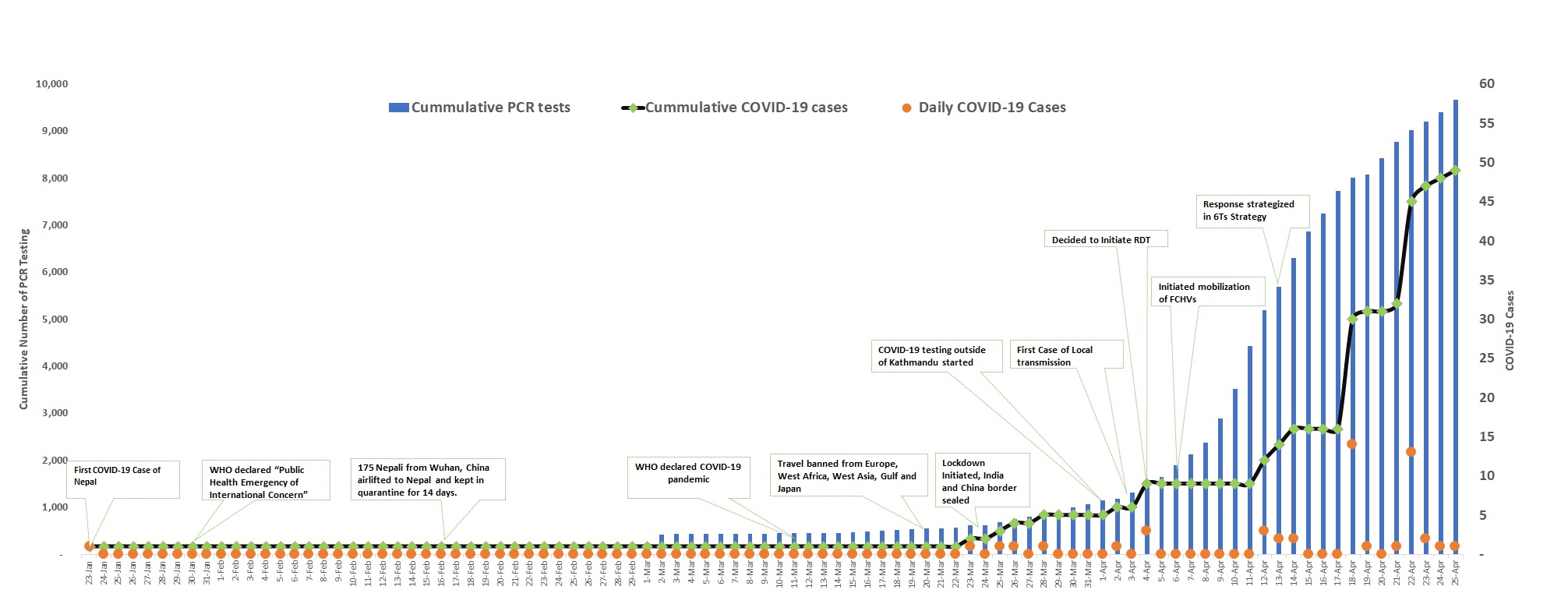

In a rural setting, where the tech driven contact tracing is almost non-existent, engaging local governments has been the most viable option. Few municipalities are also testing app-based tracking system (7) and developing own makeshift PPE sets (8). As of April 25, 2020, 14,731 individuals are in quarantine, 87 are in isolation, 49 people have been diagnosed with COVID-19, 12 have been recovered and total 49,336 tests had been performed including 9,666 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests and 39,670 rapid diagnostic test (RDT) (9). An illustration of main interventions and testing services is presented in Figure 1.

Note: These data were compiled from daily situation report of Ministry of Health of Population (MoHP). As the total cumulative tested was not presented directly in the changed format from April 18,2020, the cumulative cases has been computed by adding total positive and total negative cases. Source: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1QhLMbT76t6Zu1sFy5qlB5aoDbHVAcnHx

TheGoN decided to mobilize the wide network of 52,000 Female Community Health Volunteer (FCHVs) in disseminating right information, contact tracing, isolation and quarantine measures, and referral of the individual with COVID-19 symptoms. They can potentially be effective in risk communication, monitoring self-isolation and referral to health services. Community health workers are increasingly used to reach disadvantaged populations and combat communicable and non-communicable diseases (10). They could be one of the important cadres in responding to the COVID-19 given their proximity to local community, understanding risk and travel history. However training and PPE avaialbility is essential.

GoN has decided to form COVID-19 prevention group (CPG) in every ward: the lowest administrative unit of the country. Under the coordination of elected ward chair and supervision of health workers and FCHVs, this group is entrusted with the responsibility to disseminate message to prevent COVID-19, identifying the immigrants or other suspected person and isolating them for quarantine, contact tracing, referral of the suspected case, enforcing lockdown, assisting person to integrate in the family and community after the COVID-19 treatment or quarantine, and addressing the needs of vulnerable groups such as elderly pregnant, and those with chronic diseases (11).

One of the biggest challenges for the country, now, is to maintain physical distancing as GoN prepares to gradually shift towards lifting the lockdown. Equally challenging is to accelerate testing services for universal coverage (12). The other issue entangled with COVID-19 and the lockdown process is the security of the vulnerable populations such as the daily wage workers, pregnant, disabled, people facing gender-based violence and those losing employment as a result of the epidemic.

Although, Nepal has recently started implementation of social security schemes, there are several challenges with large informal sectors. In such circumstances, it is imperative to engage local government for the decentralized approach for responding to health and socio-economic needs. Therefore, the need of additional “T” tackling socio-economic and structural barriers in the 6T strategy is pivotal as COVID-19 now is not only the health issue and is negatively impacting all the sectors. Risk communication, testing and surveillance also will continue to be the area of attention. Mapping high risk zones and developing prompt alerts need to be integrated within the current response.

Community participation remains central of the COVID-19 response in resource constrained setting such as Nepal. The current strategy of mobilizing FCHVs, health workers, local non-governmental organization (NGOs), community advocates under the leadership of local governments will enable decentralized response mechanism for disaster and epidemic prevention and control in a setting with multiple challenges.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Dr. Samir Kumar Adhikari, Ministry of Health and Population, for supporting us with some of the data for analysis.We also thank Chetan Nidhi Wagle, Senior Public Health Officer, Health Office, Surkhet, for permitting us to use the photograph for the blog.

Authors

Navaraj Bhattarai, MPH , Nepal Public Health Research and Development Center, Kathmandu, Nepal,

Rajshree Thapa, MPH , Department of Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia,

Kiran Acharya, MPH, New ERA, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Kiran Bam,MPH, Public health professional working in Nepal. He tweets at @bamkiran

Bhagawan Shrestha, MPH , Public health professional working in Nepal.

Competing interests

We have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and we have no relevant conflicts of interests to declare.

References

- Ministry of Health/Nepal, New ERA/Nepal, Nepal Health Sector Support Program – NHSSP/Nepal, ICF. Nepal Health Facility Survey 2015. Kathmandu, Nepal: Ministry of Health and ICF; 2017.

- Neupane A. “Nepal has just one ventilator for 114,000 people” [Internet]. Republica. 2020. Available from: https://myrepublica.nagariknetwork.com/news/nepal-has-just-one-ventilator-for-114-000-people/ (Accessed on April 25, 2020.

- Piryani RM, Piryani S, Shah JN. Nepal’s Response to Contain COVID-19 Infection. J Nepal Heal Res Counc Vol 18 No 1 Vol 18 No 1 Issue 46 Jan-Mar 2020 [Internet]. 2020; Available from: http://www.jnhrc.com.np/index.php/jnhrc/article/view/2608

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). World Health Organization (WHO). 2020. RCCE Action plan guidance COVID-19 preparedness & response. Available from: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/71026_20200315whoworldwidecovid19rcceguid.pdf

- The Record. Covid19 Roundup, 13 April: 14 cases nationwide, govt’s 6T strategy & PM’s New Year address. April 13, 2020. Available from: https://bit.ly/2S87h2D. Accessed on April 25, 2020.

- Thapa R, Bam K, Tiwari P, Sinha TK, Dahal S. Implementing Federalism in the Health System of Nepal: Opportunities and Challenges. Int J Heal Policy Manag [Internet]. 2019;8(4):195–8. Available from: http://www.ijhpm.com/article_3579.html

- Smart Palika. Quarantine Management & Live Tracking System for COVID-19 Response. Available from: https://smartpalika.org/covid-19-response-system/. Accessed on April 25, 2020.

- March 27, 2020. Surkhet factories begin manufacturing of PPE. Available from: https://bit.ly/2Y372d5. Accessed on April 25, 2020.

- Ministry of Health and Population. Health Sector Response to Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Sunday |13 Baisakh 2077 (April 25, 2020) [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/19KyYDfZ3KHoJfWWp2eOaQkrvDIbfhss-. Accessed on April 25, 2020.

- Neupane D, McLachlan CS, Mishra SR, Olsen MH, Perry HB, Karki A, et al. Effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention led by female community health volunteers versus usual care in blood pressure reduction (COBIN): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Glob Heal. 2018 Jan;6(1):e66–73.

- Office of the Prime Minister and Council of Ministers. Guideline for mobilising the volunteers in the community for prevention and control of Covid-19. 2020. Available from: https://www.publichealthupdate.com/guidelines-for-volunteer-mobilization-in-the-community-for-the-prevention-and-control-of-the-corona-pandemic-2076/. Accessed on April 25,2020.

- Pesec M, Ratcliffe H, Karlage A, Hirschhorn L, Gawande A, Bitton A. Primary Health Care That Works: The Costa Rican Experience. Health Aff. 2017 Mar 1;36:531–8.