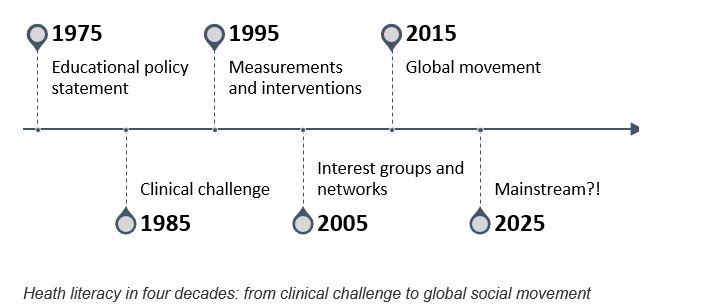

The health literacy field is developing exponentially. Four decades ago it was alluded in an educational policy statement and later considered a challenge for filling in medicial forms and a barrier for communication and clinical practice. It was an issue discussed by few. Today, the collective health literacy actions characterise a global social movement on the rise[1].

Health literacy is closely linked to literacy and entails the knowledge, motivation and competencies to access, understand, appraise and apply information for making decisions concerning healthcare, disease prevention and health promotion to improve and maintain the quality of life during the life course with support from relevant professional stakeholders. The social and political developments have occurred because the case of health literacy has turned out to be evident, measurable, feasible and for the public good.

Research has shown health literacy to be a significant public health challenge which needs attention. According to international studies 30-65% face problems with limited health literacy which can cause inequalities for patients and economic drains of healthcare budgets due to the lack of targeted treatments and timely and appropriate care and communication.

In response to the challenge, interest groups and networks have formed across the world working for the common goal of creating health literate societies. Together they form a rising social movement building on purposeful, organised efforts which drive social change towards better health for all. The collective and persistent actions forming the movement happens locally, nationally and internationally. At this stage, health literacy actions are not only grounded in research and practice. Policies mandate them at the highest political levels. Global health stakeholders such as the World Health Organization (WHO), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the European Commission have all encouraged the Member States to increase the investment in health literacy.

Social movements are developed to impact health and care for various purposes:

- bring about change in the experience and delivery of healthcare,

- improve people’s experience of disease, disability, or illness,

- promote healthy lifestyles,

- address socioeconomic and political determinants of health,

- democratise the production and dissemination of knowledge,

- change cultural and societal norms, and

- propose new health innovation and policymaking processes.

The social movements are described theoretically to go through four different stages: emergence, coalescence, bureaucratisation, and decline . In the first stage, there is little to no organisation. In the second stage leadership emerges, obstacles are tackled, and a strategic outlook is applied. The third stage includes bureaucratisation and formalisation. Finally, the fourth stage in the social movement lifecycle concerns either decline or institutionalisation. Following the developments in the health literacy field, it becomes clear that countries in the African region and South America are in the first stage, while Asia-Pacific is in the second with a few states moving into the third stage. The countries in Europe are widely spread in phase one, two, three and four, while North America is primarily in stage three moving towards four.

Rather than a declining interest, it is predictable that health literacy is becoming mainstream because of its steady recognition as an international performance indicator for population health, for health literate organisations and settings and as a cornerstone for improving the sustainable development goals. Health literacy has come to stay, and developments occur fast; hence health professionals should be alert to its importance. Recognising, respecting, and responding to health literacy as an asset for people´s health and wellbeing and organisations´ agility will improve the health system’s responsiveness and sustainability overall.

In practice, to bridge the health literacy gap, interventions can be carried out for individuals as well as organisations, communities and settings. It is essential that they build on local wisdom, respect diversity and is culturally sensitive. By humanising health systems through health literacy, professionals can enhance the fit of the services to match the actual complex demands of the people they try to help. No size fits all. Instead, new interventions can benefit from both big data and small data to accommodate tailored and personalised solutions for patients and citizens at the individual level as well as population levels. Building health literacy while focusing on people-centredness and participatory health services where patients are active partners will help save lives, save time and save resources for the public good. According to the United Nations, it is time to deliver. Integrating health literacy into standard health system procedures and responsiveness at all levels ensures that no one is left behind.

About the author:

Kristine Sørensen is founding director of the Global Health Literacy Academy, Denmark. She is the first President of the International Health Literacy Association and Chair of Health Literacy Europe. She is also a member of the WHO Technical Advisory Group on Health Promotion in the SDGs.

Kristine Sørensen is founding director of the Global Health Literacy Academy, Denmark. She is the first President of the International Health Literacy Association and Chair of Health Literacy Europe. She is also a member of the WHO Technical Advisory Group on Health Promotion in the SDGs.

Competing Interest: I have read and understood the BMJ Group Conflicts of Interests Policy and Declare I do not have any conflicts of interests

[1] In press: Sørensen et al. (2018) Health literacy and social change: exploring networks and interests groups shaping the rising global health literacy movement. Global Health Promotion.