“What is a life worth?” is a question that nobody can answer and should perhaps remain unanswered. But there are circumstances in which it is in everybody’s interest to give an answer, not an answer in poetic words or any words but an answer in pounds and pence or dollars and cents. One of those circumstances was after the deaths at 9/11, and the film Worth, which we watched a few nights ago, gave a dramatically strong account of how a group of lawyers went about answering the question for the 3000 people who died at 9/11.

“What is a life worth?” is a question that nobody can answer and should perhaps remain unanswered. But there are circumstances in which it is in everybody’s interest to give an answer, not an answer in poetic words or any words but an answer in pounds and pence or dollars and cents. One of those circumstances was after the deaths at 9/11, and the film Worth, which we watched a few nights ago, gave a dramatically strong account of how a group of lawyers went about answering the question for the 3000 people who died at 9/11.

It could have been left to the courts to answer the question. Those who lost loved ones could have sued the airlines or some other party, but that process would have taken years, the parties with the best lawyers (the airlines) would have done best, much of the money would have gone to lawyers, and there could have been serious damage to the whole US economy. It made much more sense to set up a fund and distribute the money, but who would want to lead the fund (be the master, in legal jargon) and answer the question to the bereaved of what their loved ones’ lives were worth in dollars and cents?

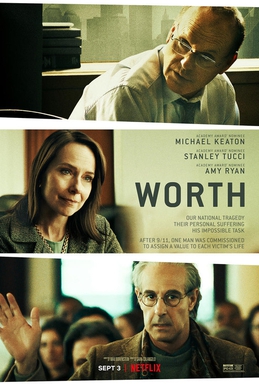

The lawyer, Kenneth Feinberg (played utterly convincingly by Michael Keaton), stepped forward, seeing running the fund as a public duty. Wisely he asked to do the job without payment: better to answer an unanswerable question without payment rather than for profit.

For Feinberg the job was simple: you did the maths, devised a formula for the worth of each life, set a time limit (two years), got people to sign up, and then divided up the money. The formula would do the work. It wasn’t for him and his team to negotiate, or everybody would be negotiating. It wasn’t for them to deal with grief. That was somebody else’s job. “We are not psychiatrists,” said Feinberg.

The big challenge was to get 80% to sign up, foregoing their right to take legal action. If 80% could not be reached then the fund collapsed, and everybody would have to go to law. A time limit was essential, or else people would keep hanging on, hoping for more.

How to set the formula? The film understandably didn’t dwell on the detail, but we understood that it was a combination of earning potential and number of dependents. Why not just divide the money by the number of dead and ascribe the same value to each life? For the religious all lives are precious: only God can decide who will live and die and the worth of a life. But the 80% target would not be reached if the relatives of the many CEOs and lawyers killed were going to get the same as cleaners and janitors.

A defining scene in the film is when Feinberg tries to explain the process and formula to the bereaved relatives. For him it’s simple, and he quickly loses the audience, especially when he says, “that’s not the game,” a very unfortunate word. “Are you saying that the deaths of those we loved is a game?” He is saved by Charles Wolf (played attractively but not convincingly by Stanley Tucci), who urges the audience to be civil, but also describes himself as Feinberg’s severest critic. Wolf ran a campaign Fix the Fund on behalf of the bereaved and managed to have the fund modified—for example, to include those who were damaged by having to work in the dust and asbestos that swirled around after the collapse of the buildings.

Feinberg and Wolf are after the same thing: fair and rapid compensation for that which cannot be compensated. The difference is that Feinberg sees it as a technical process, whereas Wolf recognises that it’s about feelings, stories, relationships, and memories. Many people are more concerned to share their stories and have them recorded than they are to receive money. After a “dark night of the soul,” Feinberg realises his mistake, and he and his staff aim to meet and listen to everybody.

The film cannot tell 3000 stories, but it has some powerful stories told directly to the camera. I imagine that these were real stories told by actors, but they could have been told by the bereaved themselves. One was the story of a wife who sat for four days beside her husband with 90% burns, only to learn that it was not him at all.

Two stories were picked as illustrating the complexities. One was of a woman who greatly loved her firefighter husband who died: “we had so many plans and dreams.” They had three sons. A lawyer contacts the Feinberg team to say that he is representing the mistress of the firefighter and their two daughters. Do the lawyers dare tell the wife of this other family? Feinberg thinks they must and does it himself. The wife, of course, knew but had never confronted her husband. She said how her husband had always wanted daughters and was anxious that his daughters should get compensation.

The other story was of a gay man who had lost his partner. The dead partner’s parents, his heirs, refused to accept that that their son was gay and in a relationship that was in effect (but not law) a marriage. Only if the parents consented would the living partner get any compensation. Feinberg’s team tried to persuade them, but failed. The partner got nothing.

These stories were, I suspect, composites of “real” stories.

The jeopardy in the film came from whether Feinberg’s team could reach the 80% target. A few weeks even days out it seemed unlikely—despite Feinberg having said from the beginning that there would be a rush at the end. There was a rush at the end because Wolf put his support behind Feinberg, Feinberg refused to do a deal with a lawyer representing a rich group, and the deadline loomed. In the end 97% signed up.

As I reflected on the film, I thought that I too was capable, like Feinberg, of thinking of a process as technical when in fact it depends on feelings, stories, relationships, and memories. Perhaps many of us make the same mistake. Perhaps it’s common in hospitals when people are dying. What is a life worth as it ends?

Richard Smith was the editor of The BMJ until 2004.

Image: By IMP Awards / 2021 Movie Poster Gallery / Worth Poster, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=64768255