Artificial intelligence is hardly out of the news these days.

Last week, for example, the AI company DeepMind, whose AI versions of board games such as chess and go have beaten the best players in the world, announced that they had used a program called AlphaFold to define the structures of 350 000 proteins, human and non-human. The technology is likely to lead to the discovery of many new chemical compounds that can somehow affect the functions of those proteins, although whether that will lead to effective medicinal compounds is another matter. A molecule may bind to a protein in silico or in vitro, but that is a long way from in vivo efficacy, as many examples show.

Evidence of poor collaboration between AI experts and their medical counterparts is also a concern. For example, a recent systematic review of studies on the use of AI to aid lung imaging in covid-19 showed that in only 12 of 463 studies was there close collaboration.

As another example, pharmacovigilance experts have not yet been widely involved in using AI technology. When I searched PubMed for (“natural language processing” OR NLP) & pharmacovigilance as textwords, I got 105 hits. Of those, most came from departments of computing or informatics; only a handful included individuals from pharmacovigilance centres. When I expanded the search to include “artificial intelligence”, “semantic web”, “systems engineering”, “software engineering”, “biomedical informatics”, “library science”, “enterprise bookmarking”, “information architecture”, “ontologies”, “linguistics”, “machine learning”, and “deep learning” as textwords, the number of hits increased to 212. However, only a few included authors from centres of pharmacovigilance.

A darker side of artificial intelligence has also been reported in an arXiv preprint, in which the use of probabilistic text generators to produce fake scientific papers has been highlighted. Publication of such papers, from what have been called “fake-paper factories”, with the intention of contributing to the authors’ resumés, has been going on for some time, and some have been computer generated. Their predecessors, paper mills, have been in existence for much longer. However, advances in AI technology have meant that the quality of the texts that can be generated in this way has improved considerably. Even so, fake papers can be detected by their use of terms that the authors of the preprint have christened “tortured phrases”

I have previously written about fake papers written in order to lampoon and expose intellectual claptrappery, classically, but not exclusively, in postmodernist texts. The authors of such papers typically take a nonsensical scientific position and bolster it by reference to pseudoscientific and quasi-philosophical ideas, dressed up in language that they know readers will find too obscure and daunting to challenge. Examples of the papers that they have lampooned in this way are not difficult to find. Intellectual Impostures by Alan Sokal and Jean Bricmont, also known as Fashionable Nonsense, is an excellent primer on the subject.

Tortured phrases arise when, as the arXiv authors put it, in their own slightly tortured way, “a word-by-word synonymical substitution is applied to a multi-word term”. Rather than attempting to define more clearly what they mean, I offer some illustrative examples: “versatile organization” (i.e. mobile network), “motor vitality” (kinetic energy), and “discourse acknowledgement” (voice recognition).

Tortured phrases can arise when a phrase is translated from one language to another and then back-translated into the original language. For example, when computer translation was first essayed in the 1960s it was whimsically suggested that a foreign computer, as it might be Russian or Japanese, had translated “out of sight out of mind” as “invisible, insane”. Today, if you enter the proverb in English into Google Translate and then ask it to back-translate the Japanese version into English, you get “In the invisible head”, which isn’t quite as striking. Much better was the title of a 1987 book by Wendy Hunter Williams, Out of Mind, Out of Sight: the Story of the Porirua Hospital. There may be earlier examples, and the phrase has often been used since, in the titles of books, articles, record albums, and documentaries.

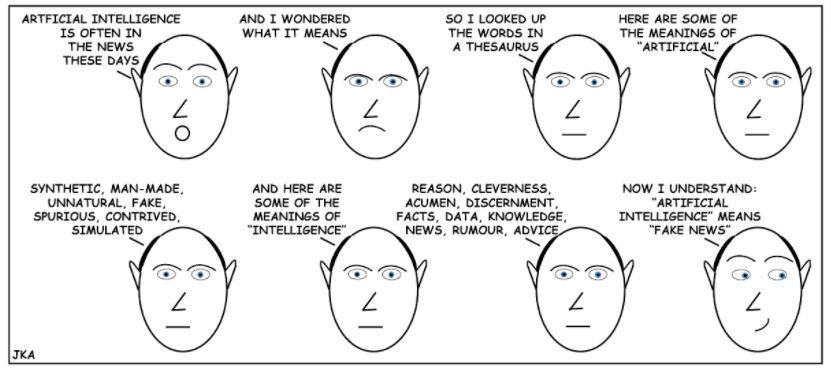

Another example of the tortuously torturous technique is shown in the cartoon below.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: none declared.

1) https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/07/17/jeffrey-aronson-when-i-use-a-word-movements

2) https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/04/24/%20jeffrey-aronson-when-i-use-a-word-exponential-finances-increasing-decreasing