The battle to prioritise people with learning disabilities for the covid vaccine may be won, but did negative stereotypes and outdated prejudices have to be reinforced to get there?

Over the past year, people with learning disabilities have been told to “shield” and “self-isolate,” with little accessible communication about what these terms mean. Some have had inappropriate “do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation” notices placed on their hospital files, and many have died in much higher numbers than the general population, with researchers estimating that people with a learning disability have had a six times higher death rate from covid-19.

In recent weeks high profile figures have lent their voices to the call for this group to be vaccinated against covid-19 without delay. Celebrities like Jo Whiley and Ian Rankin, respectively the sister and father of a person with a severe learning disability and both Mencap ambassadors, made public pleas for this group to be prioritised for the vaccine. No sooner had Jo Whiley spoken up than the nation looked on as her sister Frances contracted covid-19. The intense media attention that accompanied Frances’s illness achieved more in a short time than families, scientists, and campaigners had over months of imploring the government to pay more attention to the needs of people with learning disabilities.

Now that people with learning disabilities (or rather the quarter to a third who are recognised as such on GP registers) are prioritised for vaccination, it is time to examine what has been gained and lost in the process.

We should make space to hear the experiences of the 1.5 million people in the UK who have a learning disability but whose voices have been, once again, almost entirely absent in the media reporting. For the four of us (CB, AB, HR, and PD) who speak as people with a learning disability, we see too little progress. Some people with learning disabilities are very vulnerable, but many of us can stand up for ourselves and we can contribute to our communities. Narratives that frame us as a burden on our families or the NHS negate our humanity and worth as loved and valued individuals. It’s 2021: there are 1.5 million of us in the UK and we have a right to be treated better and more fairly.

Researchers have long alerted the NHS and healthcare providers to the crushing health inequalities experienced by people with learning disabilities. Society as a whole and the government have largely turned a blind eye to the severe deprivation, social inequalities, and multiple barriers to accessing good quality health and social care which are the norm and not the exception for people with learning disabilities. Michael Marmot, a leading researcher on health inequalities, aptly noted in introducing an NHS commissioned report that this population group are more likely to experience “some of the worst of what society has to offer,” including low incomes, unemployment, poor housing, social isolation and loneliness, bullying, and abuse. The same report called for more efforts to integrate people with learning disabilities into society and to reduce stigma and discrimination as a way to improve their lives and health outcomes.

Unfortunately, during the pandemic, people with learning disabilities’ increased risks from covid-19 haven’t been understood and presented as an outcome that takes place against a background of severe health inequalities. Instead, it was recourse to the traditional story of people with learning disabilities as “vulnerable” and “helpless” that dominated in the media, and which finally moved the government to act. This story once again minimises the agency and capabilities of people with learning disabilities. It’s yet another pillar propping up the negative stereotypes that people with learning disabilities and their allies have challenged for the past few decades.

Our STORM project places people with learning disabilities at the centre of efforts to challenge the prejudice and discrimination they still frequently face in their everyday lives. As we say to anyone with a learning disability in the introduction to our STORM manual, borrowing the words of the Nobel Prize winning writer Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie: “Your solid unbending belief should be: I matter. I matter equally. Not ‘if only.’ Not ‘as long as.’ I matter equally. Full stop.”

If this statement sits uncomfortably with healthcare providers and policy makers when thinking of people with learning disabilities, we invite them to reflect on their perceptions. What is it that leads you to think of this population as lesser? Why do you address their parent or supporter when they present in your surgery or hospital? What might you and many of your patients gain if you stopped for a moment, slowed down a little, and used straightforward words to explain things? Doing so would not only pay people with learning disabilities the respect they deserve, but also benefit the other 8.5 million people in the UK whose literacy skills are very poor.

We await the rollout of the new Oliver McGowan mandatory training in learning disability and autism for all health and social care providers. In the meantime, GMC guidance and patients with learning disabilities offer some straightforward tips for healthcare providers on how to make reasonable adjustments and avoid discrimination. It is not just a matter of training though: a fundamental belief in this population group as deserving of good quality and equal care is needed on the part of all health and social care providers.

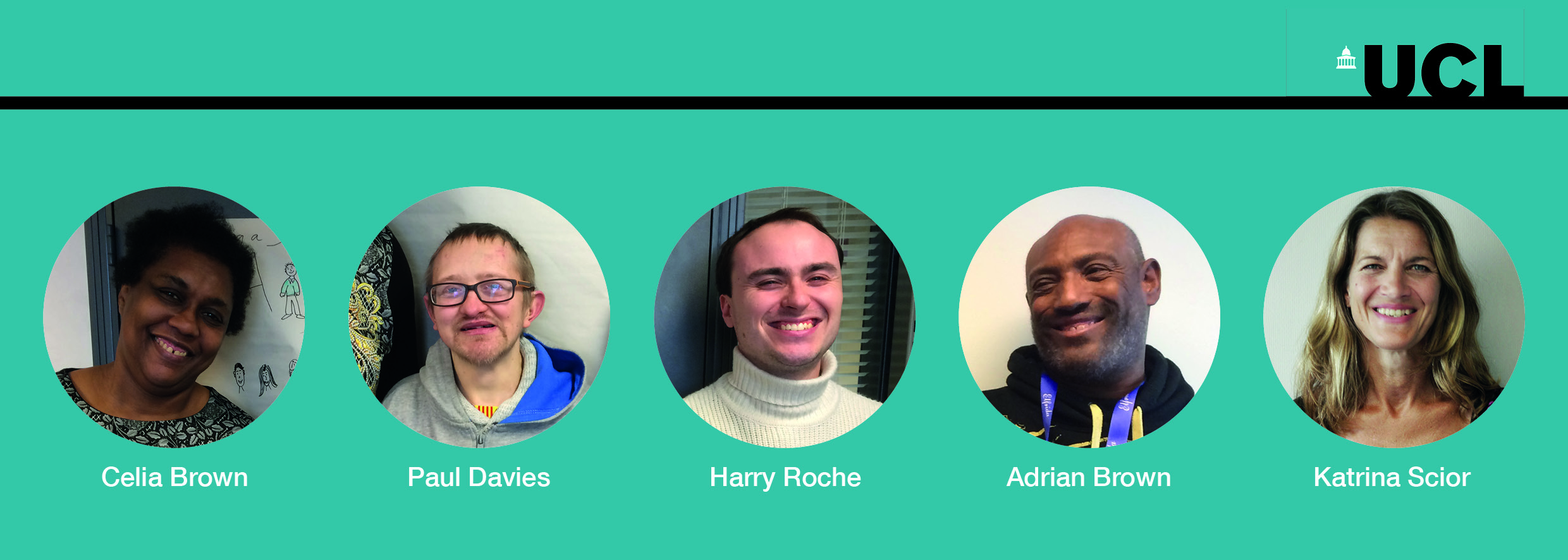

Katrina Scior is a professor of clinical psychology and stigma studies at UCL. Twitter @kscior @uclusresearch

Celia Brown is a self-advocate expert adviser on the NIHR funded STORM Project.

Adrian Brown is a self-advocate expert adviser on the NIHR funded STORM Project.

Harry Roche is a self-advocate expert adviser on the NIHR funded STORM Project.

Paul Davies is a self-advocate expert adviser on the NIHR funded STORM Project.

Competing interests: none declared.