Although it may currently be difficult and uncomfortable to recognise, the covid-19 pandemic is not the world’s major threat to health. The climate crisis is the major threat. The pandemic, like the pandemics before, will eventually fade with covid-19 becoming an endemic, but probably less serious disease. The climate crisis, which is killing people today across the world, will not fade without concerted global action. It is progressing remorselessly at a lethal pace—slow enough to make it too easy for governments to put off actions until tomorrow, but fast enough that without increased action it will cause a health and environmental catastrophe for young people alive now. But concerted global action now can avert much of the damage and bring health benefits, particularly if maximising health is put at the centre of that action, as is shown by a special issue of The Lancet Planetary Health.

And this is the year for action, spurred on not impeded by the covid-19 pandemic to avoid one public health crisis merging into another. The annual United Nations meeting on climate change, COP26, will be held in Glasgow at the end of the year and this is the most important meeting since the Paris meeting of 2015 when 196 states committed to reducing temperature rise to “well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels.” At that meeting the countries declared nationally determined contributions (NDCs) to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases, but as they stood at the end of 2020 the contributions are inadequate and will lead to an increase of 3°C by the end of this century. Increases above 1.5°C run the risk of feedback loops and complete loss of control over the climate, which is why the UK Health Alliance on Climate Change (which I chair) and its 22 member organisations have a Call to Action to keep the temperature rise to no more than 1.5°C. (Scroll down to see the full call.)

Increasing recognition of the difficulty of achieving a rise of not more than 1.5°C has led some to propose changing the target, but the Alliance thinks it essential to continue to aim for 1.5°C. Sticking with the target makes stabilisation of temperature and even subsequent falls much more likely.

Health is not one of the five priorities of COP26, but all five—adaption and resilience, energy transition, clean transport, nature, and finance—have strong health connections. Health has never been a priority in any of the 25 COPs, but the central argument of the special issue of The Lancet Planetary Health is that adopting a focus on health brings substantial benefits. Recent research has shown the best way to encourage those currently not concerned about the effects of climate change to become concerned is framing the climate crisis as a health issue and emphasising the benefits to health of the changes that need to be made. Helping people to understand that the effects on health are already here also prompts increased concern.

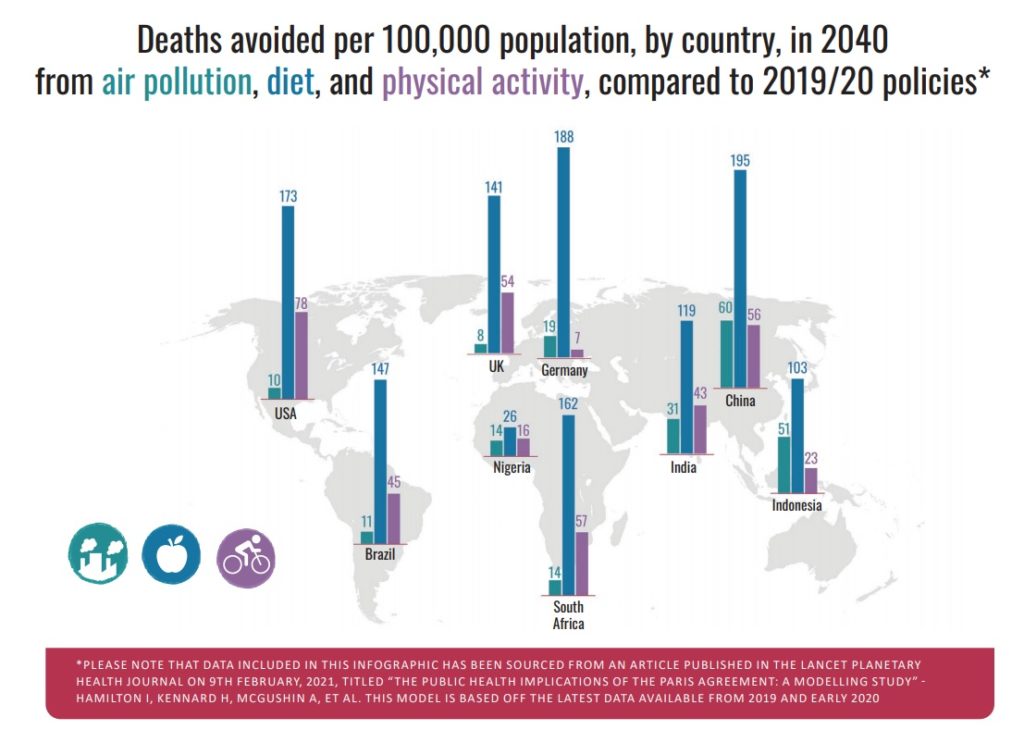

The Lancet Planetary Health authors have modelled the impact on deaths in 2040 in nine countries in three scenarios: NDCs and accompanying policies stay as now (and remember that the countries are not on track to achieve them); NDCs are increased to achieve the Paris target and the Sustainable Development Goals; and NDCs are as in the second scenario but achieved with health at the centre of all policies. The model examines deaths related to diet, physical inactivity, and air pollution resulting from policies adopted in food and agriculture, transport, and energy sectors. The authors have concentrated on deaths because they are easier to model, but I think that it’s important to remember that most deaths are associated by years of suffering and many suffer from a wide range of health problems, including mental health problems, without dying prematurely.

In the scenario that puts health at the centre of policies to achieve the Paris target policymakers seek to maximise health benefits with more ambitious actions to encourage healthy eating, being tougher on air pollution, and maximizing opportunities for walking and cycling. Such policies would fit with the public being supportive of policies that promote health, as the UK Climate Assembly showed.

The countries studied are Brazil, China, Germany, India, Indonesia, Nigeria, South Africa, the UK, and the USA. These countries account for 70% of global greenhouse gas emissions and half of the global population. Only India has an NDC that is compatible with a temperature increase of no more than 2°C. All the other countries existing NDCs are insufficient to achieve that goal. Revised NDCs for COP26 were supposed to be submitted by the end of 2020, but so far only three of the countries studied have submitted theirs, giving them time to improve them in the light of this study.

Achieving the Paris agreement would in the year 2040 save 1·18 million deaths from air pollution, 5·86 million from poor diet, and 1·15 million death from physical inactivity. The biggest improvements per 100 000 people would be seen in Indonesia, China, and India.

Going one stage further and putting improving health at the centre of policy making would cause a further reduction of 370,000 annual deaths with the biggest reductions again in middle-income countries.

Between now and 2040 producing and implementing NDCs that achieve the Paris target and adopting policies that maximise health benefits would in total save just over 10 million deaths (1.6 million from air pollution. 6.4 million from poor diet, and 2.1 million from physical inactivity).

All these gains depend on targets being met, and it much easier to set a target than to achieve it. High-income countries have largely caused the problem with more than a century of producing greenhouse gases, but it is low-income countries in SubSaharan Africa and South Asia that are destined to suffer the most from the climate crisis. Low-income countries will need to consume carbon to develop, which is why a just and logical policy is for rich countries to have lower carbon allocations than poorer ones and for there to be a transfer of funds from richer to poorer countries. Part of the Paris Agreement was to transfer funds from richer to poorer countries, reaching a target of $100 billion a year by 2020. That target was not met, but it may have come close to $80 billion.

The world and particularly the young need ambitious NDCs that are met and a global transfer of funds from rich to poorer countries on an adequate scale. Just as countries need to work together to counter the covid-19 pandemic, particularly with sharing vaccines, so the world has to work together to achieve a global increase of temperature of no more than 1.5°C. No country, no matter how powerful, can solve the climate crisis alone.

Health professionals, one of the most-trusted groups in all societies and enjoying increased global respect because of their work in the pandemic, have a crucial part to play in mitigating the climate crisis. The Global Health and Climate Alliance, the UK Health Alliance on Climate Change, and many other climate and health organisations will be working throughout the year leading to COP26 and beyond to encourage the world to do all it takes to stay below 1.5°C. It means action at a global, national, local, organizational, and individual level, and you can join UKHACC in its work and campaigning here.

Richard Smith was the editor of The BMJ until 2004.

Competing interest: RS is the unpaid (but hard-worked) chair of UKHACC.