In our recent survey of harms at Christmas, Robin Ferner and I did not discuss the harms that might arise from having seasonal plants in the vicinity, other than Christmas trees.

In a PubMed search for plants connected to Christmas I find that mistletoe is the most often discussed. For example, “holly” yields 1775 hits (excluding the many authors called Holly and addresses such as Holly Springs, North Carolina).”Ivy” garners 1288 hits, again omitting authors’ names and institutions such as Ivy Hospital, Mohali, Punjab. “Mistletoe” yields 1603 hits, beaten by “holly”, but restricting the search to titles, mistletoe wins handsomely: 819 hits versus 533 for “ivy” and only 96 for “holly”. Perhaps it’s because mistletoe is a parasite.

Surprisingly, the word “mistletoe” comes from MEIGH, an IndoEuropean root meaning to urinate, which is what a now obsolete English word, mighe, first mentioned in Bald’s Laeceboc, meant. Bald, probably a physician, commissioned his leechbook from one Cild, probably a writer or compiler, in the early tenth century, using recipes from the court of King Alfred. From “mighe” we get miction (urination) and micturition, which originally meant an intense desire to urinate or excessive frequency or volume of urination, but whose meaning has been, so to speak, watered down. In Sanskrit megha means mist, vapour, or a cloud, as ὀμίχλη did in ancient Greek, in which it also meant the steam from cooking and cloud-like darkness or gloom. Via mostly Germanic intermediaries, this comes out as “mist” in English. Mizzle is very fine misty rain or drizzle, in Scotland called smirr.

The word mistle, describing the plant we now call mistletoe may have arisen through fanciful comparison of mist with bird excreta, which may cover it—the mistle thrush is so called because it feeds on the plant and excretes the seeds. The word was originally “mistletan”, where “tan” means a twig, but because “tan” is also the plural of “ta”, meaning a toe, the two words became confused through folk etymology, resulting in mistletoe.

The prose Edda relates the Norse legend that Baldur, the son of the goddess Frigga and her husband Odin, was the most beautiful of the Aesir and much resented by Loki. After Frigga had persuaded all things to agree not to harm Baldur, the gods played a game of throwing things at him. Loki discovered that the mistletoe had been left out of Frigga’s calculations and persuaded the blind god Hodur to throw some at Baldur, who died as a result. In The White Goddess (1948) Robert Graves recounted how he had once cut a spear out of mistletoe and declared that the wood was hard enough to have caused Baldur’s death, “no poetic fancy”. Frigga’s tears, in one version of the myth, fell on the mistletoe and produced its white berries.

The IndoEuropean root WEIS meant to flow. In Latin this gave viscum, mistletoe, referring to the sticky, viscous, substance (bird-lime) found in its berries, which can be smeared on the branches of a tree to trap birds that land on it. Mistletoe belongs to the family of Viscaceae or Loranthaceae, whose seven genera include Arceuthobium (dwarf mistletoe), Korthalsella (korthal mistletoe), Phoradendron (American mistletoe), and Viscum itself.

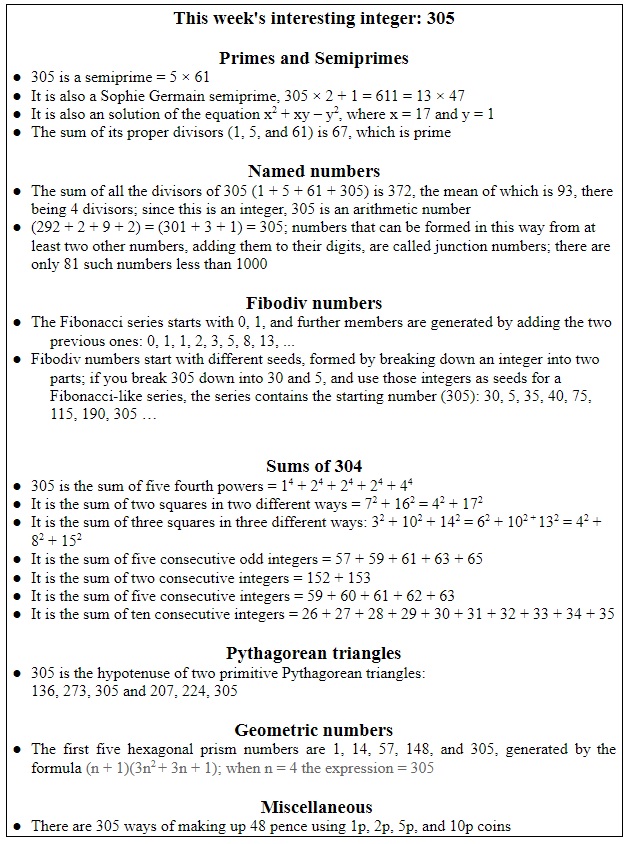

In clinical medicine there are two different mistletoe signs (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Left A 69 year old woman with symptoms of presumed cardiac involvement of idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis (Ormond disease) had pericoronary artery tissue growths resembling mistletoe seen at cardiac MRI; the authors suggested that this rare appearance, which they called the mistletoe sign, might be a characteristic effect of retroperitoneal fibrosis (from Maurovich-Horvat et al. Radiology 2017; 282(2): 356–60)

Right The “mistletoe sign” in a skin lesion, shown by dermoscopy, proposed to indicate a melanoma in situ or a melanocytic junctional nevus (from Kamińska-Winciorek et al. Postepy Dermatol Alergol 2013; 30(5): 316–19)

Viscum album (all heal, bird lime, devil’s fuge, golden bough (Figure 2), or mistletoe) was venerated by the Celtic druids and regarded as having healing properties, although a PubMed search for “mistletoe & covid” produced no hits. In vitro, extracts of mistletoe, which contain viscotoxins, polysaccharides, and lectins, can kill cancer cells and down-regulate genes that code for substances involved in malignancy, tumour progression, and cell migration and invasion, such as TGF-β and matrix metalloproteinases. They may also be antiangiogenic. However, in vitro effects often do not translate into clinical efficacy, and, to quote a PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals, “many of the studies [of mistletoe in cancers] had major weaknesses that raise doubts about the reliability of the findings”.

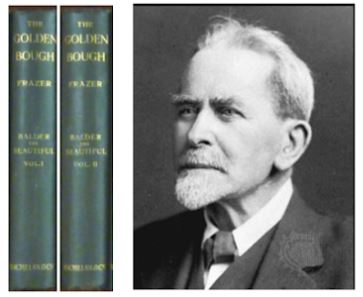

Figure 2. Sir James George Frazer (1933) and the two “Baldur the Beautiful” volumes from the 12 volumes of the 1935 3rd edition of his study of comparative religion, The Golden Bough (1913). Frazer recounts Baldur’s story and many of the myths surrounding the mistletoe and gives several reasons for its having been called the golden bough

Adverse effects of mistletoe extracts are uncommon, but skin reactions and anaphylaxis can occur. In one case, mistletoe lectins may have caused subcutaneous lymphomatous nodules at injection sites, by liberating high concentrations of interleukin-6.

So now, having learnt all this, and with the origin of the custom unknown, do you still want to kiss under the mistletoe?

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.