Failures in the design and evaluation of England’s Test and Trace programme could be resolved if we collect some core data, says Sheila Bird

On 23 July 2020, the Royal Statistical Society made three recommendations to remedy NHS Test and Trace’s failures to glean intelligence. [1] So far these have not happened.

The first was a need for information about the rate of developing symptoms and testing positive for two high-risk groups whom NHS Test and Trace seeks to quarantine:

- a) people living in the same household as a confirmed covid-19 case

- b) external close contacts of a confirmed covid-19 case

Second is the need for robust intelligence about asymptomatic swab-positive rate in the first five days of quarantine and in the next nine days for these two high-risk groups. Gathering this intelligence would require home visits on two randomly sampled days.

Third is the need for proper auditing about people’s adherence to the “stay at home” instruction, which can be done efficiently as part of the above random home visits.

Two months later, what is the situation now?

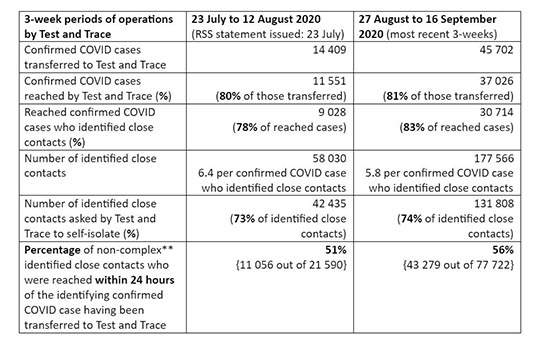

Compared to the 3-weeks beginning 23 July 2020, referrals to NHS Test and Trace trebled during 27 August to 16 September 2020 as 45,702 people with confirmed coronavirus symptoms (that is: symptomatic index cases) were referred to NHS Test and Trace. [2] NHS Test and Trace reached 37,026 of them, but only 30,714 (67%) identified any close contacts. Of 177,566 identified close contacts, only 131,808 (74%) were asked to self-isolate. Moreover, only 56% were asked to self-isolate within 24 hours of their non-complex symptomatic index case having been referred to NHS Test and Trace. Hence, fewer than 3 in 10 close contacts are asked to self-isolate within 24 hours of their symptomatic index cases being transferred to NHS Test and Trace. [3] But the infectiousness clock starts ticking from two days before the index case developed coronavirus symptoms.

Random visits to offer swab tests have not yet been instigated. This is despite the fact that if these visits occured, one could expect 10 times as many positive swab tests per 1000 visits as ONS’s community-wide surveillance records, precisely because the household members and external close contacts identified by NHS Test and Trace are at specific high-risk. [1,4] The NHS Test and Trace service has comprehensively failed to quantify just how high their risk is and to define the characteristics of those most likely to be confirmed as covid-19 cases during their quarantine.

England’s Test and Trace service has also failed, so far, to gain critical intelligence about asymptomatic infections and their transmissibility—a known “unknown” highlighted in the Royal Society’s recent report. [5, 6]

An added criticism is the service’s expensive failure to audit adherence to its stay-at-home instruction. Throughout June and July 2020, surveys of 2,000 respondents weekly showed consistently that good intentions to self-isolate for 14 days (by 70% of respondents) fell short in practice – being achieved by fewer than 2 in 10 of around 400 who were actually quarantined. [7] Shortfall is, of course, inevitable if the close contact is not even reached by NHS Test and Trace until several days into his/her intended 14-day quarantine period.

To achieve the three key epidemiological objectives highlighted by the Royal Statistical Society’s COVID-19 Taskforce, NHS Test and Trace needs to ensure that core data are rigorously collected and made available centrally for analysis. Demographic information, as in the ONS Infection Survey, is also important.

The core data we need:

The symptom-onset date for each symptomatic index case, not just the swab-date or referral-date to NHS Test and Trace.

Why? First, because it is from two days before the symptom-onset date that the index case is asked to recall and identify all their external close contacts. Second, because the quarantine period for each external close contact begins from their most recent close encounter with the symptomatic index case, which may have been as early as two days before the index case’s symptom-onset date.

Three key dates for each identified external close contact—the date of their most recent close contact with the index case, the date when the close contact was reached by NHS Test and Trace, and the end-date of the close contact’s quarantine.

Why? Because, for external close contacts (b) reached by NHS Test and Trace, the number of days that they are asked to “self-isolate” depends on how quickly the service reached them and may be fewer than 14 days for that reason alone.

A key performance indicator for NHS Test and Trace is therefore the number of “self-isolated days” (out of a possible 14 days) that each identified external close contact is asked to comply with. For identified external close contacts who are never reached, that number is zero.

The number of household members (a) and of external close contacts (b) of symptomatic index cases who develop coronavirus symptoms and have positive swab tests.

England’s Test and Trace service should know, if it holds the core data outlined above, when the intended quarantine period ends for the majority of its high-risk group members. But NHS Test and Trace also needs to ensure that the person-identifying information held on members of its high-risk groups (for 28 days only) matches the information that is held about people who have developed symptoms and got a positive swab test.

This matching requirement is elementary to state, but tricky to deliver. England lacks a personal identifier, unlike in Denmark. Scotland’s use of Community Health Index numbers helps out Test and Protect.

Did NHS Test and Trace overlook the need to link records to discover how many newly-diagnosed covid-19 cases were recently in self-isolation? The Royal Statistical Society recommended precisely this linkage to work out how many in the quarantined high-risk groups, both within households (a) and as external close contacts (b), subsequently developed symptoms and had positive swab tests within two days of the end of their quarantine period?

Lack of design-forethought may mean that we have been saddled with mismatched identifiers, but let’s not perpetuate the fiasco. The companies engaged to deliver NHS Test and Trace need to find a solution. A phone number or email address works well enough for tracing index cases and reaching contacts; but may not match the sort of identifying information held for people who have positive swab tests.

Those engaged to deliver Test and Trace could, for example, recontact the household of each symptomatic index case to discover how many household members—if any—developed symptoms and were swab-test positive during their quarantine plus two days.

This follow-up phone call or email should also elicit and record the following information for each household member:

- gender

- age

- region

- employed or not and, if employed, whether the person’s pre-quarantine occupation was at-home versus usually working outside the home

- self-reported number of days of adherence to quarantine

- self-reported symptom-development (with date) during quarantine

- self-reported swab test during quarantine (with date and result).

Each external close contact identified should also be followed up by phone or email.

Sheila M Bird is formerly Programme Leader at the MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge

Declaration of interest: SMB is a member of the Royal Statistical Society’s COVID-19 Taskforce and chairs its panel on testing

References:

-

- The Royal Statistical Society COVID-19 Taskforce Statement on how efficient statistical methods can glean greater intelligence from Test, Trace and Isolate (TTI), officially known as Test and Trace. London; 23 July 2020. See https://rss.org.uk/RSS/media/File-library/Policy/RSS-COVID-19-Task-Force-Statement-on-TTI-final.pdf

- NHS Test and Trace (England) and coronavirus testing (UK) statistics: 10 September to 16 September 2020. See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/nhs-test-and-trace-england-and-coronavirus-testing-uk-statistics-10-september-to-16-september-2020.

- The Royal Society DELVE Initiative. Test, Trace, Isolate. https://rs-delve.github.io/reports/2020/05/27/test-trace-isolate.html#7-effective-tti-within-a-broader-epidemic-response. London: 27 May 2020.

- Office for National Statistics. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection Survey pilot: England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 25 September 2020. See https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/coronaviruscovid19infectionsurveypilot/englandwalesandnorthernireland25september2020.

- The Royal Society. Reproduction number (R) and growth rate (r) of the COVID-19 epidemic in the UK: methods of estimation, data sources, causes of heterogeneity and use as a guide to policy formulation. See https://royalsociety.org/-/media/policy/projects/set-c/set-covid-19-R-estimates.pdf?la=en-GB&hash=FDFFC11968E5D247D8FF641930680BD6. London: 24 August 2020.

- Anderson RM, Hollingsworth TD, Baggaley RF, Maddren R, Vegvari C. COVID-19 spread in the UK: the end of the beginning? Lancet 2020; 396: 587-590.

- Smith LE, Potts HWW, Amlot R, Fear NT, Michie S, Rubin J. Adherence to the test, trace and isolate system: results from a time series of 21 nationally representative surveys in the UK (the COVID-19 Rapid Survey of Adherence to Interventions and Responses [CORSAIR] study). See https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.09.15.20191957v1.