Much of the rhetoric on the coronavirus pandemic has drawn on battlefield metaphors. Perhaps the notion that truth is the first casualty of war also applies to our government’s response which has frequently been economical with the truth, although stopping short of outright lies.

In an era of instant social media, where those on the frontline of healthcare can comment on their lived experience, where reporters and policy analysts can debunk statements, cross reference to earlier ones, fact check claims and publish alternative data analyses, such approaches are totally counterproductive. When will they learn?

The aversion to the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth has come in various guises.

Firstly, we have had selective and partial presentation of data.

For instance, in March, at the daily Downing Street press briefings, the Department of Health and Social Care only presented deaths in hospital patients for whom covid-19 tests (which were in short supply) had been positive. It was only after considerable pressure from healthcare professionals and the public that they started to publish the Office for National Statistics data for deaths in all settings, including care homes, with or without confirmatory testing, and then excess deaths (from other causes) alongside those very selected mortality statistics.

Following big pledges and targets from Matt Hancock, the health secretary, for the number of covid-19 tests—apparently outside any kind of coherent testing strategy—we saw a mad dash to hit a 100,000 test a day target by the end of April. Local teams reported pressure to ensure it was met. The way subsequent testing figures have been counted has also drawn criticisms with tests sent out as home kits, or tests that had not yet been taken being counted, and ignoring the high first negative rate, meaning individuals are tested twice.

We have seen claims from government agencies that discharges from acute hospitals to care homes in March and April were far lower than in the same months in other years. These claims were quickly debunked in the Health Service Journal and on the Nuffield Trust website. By 8 June Hancock was claiming in a daily briefing that the UK had far fewer care home deaths from covid-19 than a number of other European countries. Again this was a very selective interpretation of data which are all in the public domain.

Secondly, we have seen big disparities between large, meaningless numbers and the lived realities of frontline health and social care staff or people trying to use services. Pledging 7 million pairs of gloves or 84 tonnes of personal protective equipment is meaningless if staff cannot reliably access them. This makes the contrast with ministerial media pronouncements or statements in parliament look ridiculous in their disconnect. Results matter—not intentions. The same charade has played out with big statements on care homes or hospitals being able to test all residents or staff when this has proved impossible. And with the recruitment of thousands of track and trace staff who say they have been poorly led, poorly trained, and are confused about their role.

Thirdly, there have been general claims made, free of numbers but which beggared belief. Notably that our pandemic response “has been an international exemplar in preparedness.”(as asserted by Deputy Chief Medical Officer Dr Jenny Harries) despite the UK already having around 1 in 10 of all world deaths from covid-19 and well documented failures to learn from the Operation Cygnus pandemic preparedness report, or have adequate testing or PPE capacity, or commence our response sooner in the face of World Health Organisation warnings of a threat to global public health.

Another example is Hancock’s claim that “a protective ring” had been “thrown around” care homes when it became apparent that large numbers of acute hospital patients with covid-19 had been transferred to facilities ill-equipped or staffed to cope—with predictable results.

There have also been big bold claims about the success of the tracking and tracing App piloted in the Isle of Wight and its security, as opposed to tried and tested public health methods based on humans, phones, and shoe leather.

There may still be stories to emerge about government contracts placed with private providers of PPE, or apps or the contract with Serco to deliver test track and trace. One wonders what commercial interests or lobbying have been at play?

Fourth, we have had a general tendency to secrecy, news, and message management. NHS England have done their best to maintain a tight grip on the communications coming out of trusts. There have been numerous instances of clinical staff being threatened or disciplined for speaking out about their fears for personal safety and patient care. Journalists have struggled to get access because of this omerta.

Why for instance did the government set out five rule test for easing the lockdown and then in late May, seemingly ignore the rules it had set for itself? This has yet to be explained? Why did Public Health England downgrade the pandemic from a level 4 to a level 3 when there were severe PPE shortages, thereby allowing lower levels of PPE to be recommended?

At every turn the government has had to be pushed to be transparent. For instance, they were pressed to release the names of Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) members, or the SAGE minutes, or the number of clinical staff dying from covid-19, or the release of the full details of Cygnus. Its own report on disparities in covid-19 outcomes for patients and staff from ethnic minorities was redacted and put out with minimal press release possibly in the hope that it wouldn’t be noticed or make the headlines.

It is still hard to discern to what extent the governmental response really has “followed the science” or the extent to which scientific and medical advisors have been overruled or ignored. We may not know until there is a post pandemic public inquiry.

Fifth and finally, the entire cabinet and prime minister fatally undermined its cause and credibility by mangling the truth over Number 10 strategy chief Dominic Cummings’ drive to Durham when infected with coronavirus.

The seven Nolan Principles for conduct in public life include openness, honesty, and objectivity. NHS frontline doctors and nurses are bound by a professional duty of candour, openness, and transparency.

It is about time we saw some of this from our government, its communications teams, and national agencies.

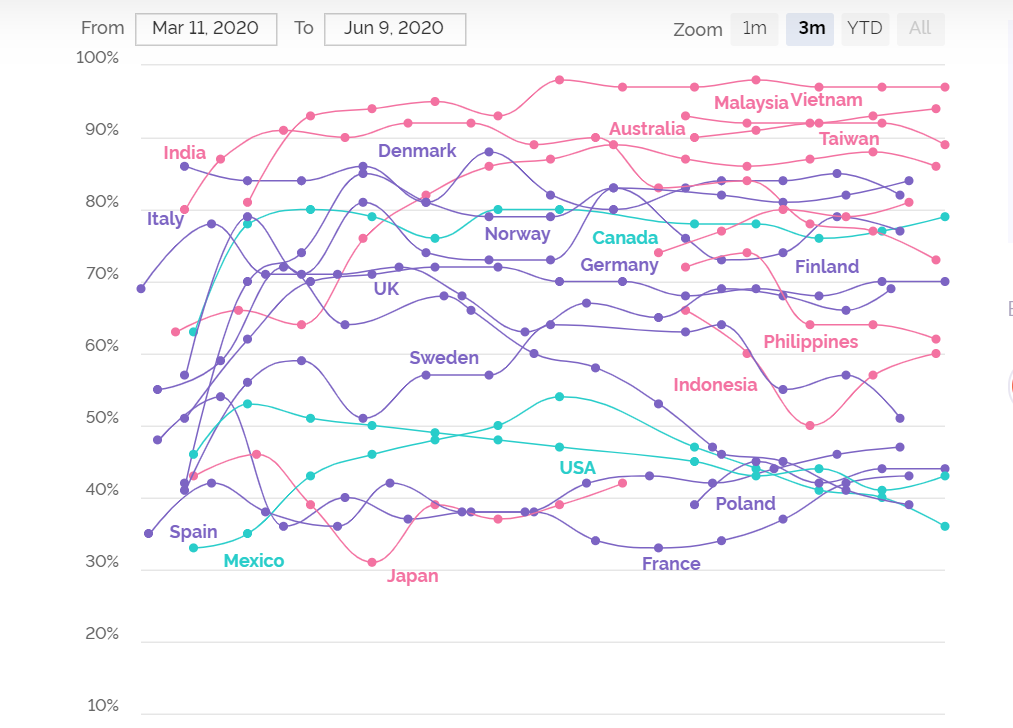

A recent YouGov poll showed that public confidence in the UK government’s handling of the Coronavirus pandemic plummeted from over 70% to 42% by 9 June even when trust in many other nations has held fairly steady. I can’t help wondering if a lack of transparency and honesty is behind some of this loss of trust. But will our government and its agencies take note?

David Oliver is an NHS consultant physician, a former Department of Health National Clinical Director, ex President of the British Geriatrics Society and Vice President of the Royal College of Physicians. He writes a weekly column in The BMJ.

Competing interests: See www.bmj.com/about-bmj/freelance-contributors.