Patient: “I’m scared about having this procedure. I’m having second thoughts.”

Doctor: “Don’t worry. Your surgeon does four hundred of these a year. You’re in good hands.”

Trainee: “I’m stressed I’m not keeping up with reading. It’s overwhelming.”

Supervisor: “Try not to worry, you’ll be fine. It’s impossible to read everything.”

Whether speaking with patients, their family, colleagues, friends, trainees, or those closest to us, we often respond initially to emotion with information or reassurance instead of starting with empathy, acknowledgement, and curiosity. 1 Providing information first in the face of emotion, or “answering feelings with facts,” can miss the opportunity to build the rapport needed to elicit and understand patients’ concerns and values. While reassurance may be caring, it often suppresses the emotion expressed. This suppression precludes the speaker from feeling heard, engendering the label “false reassurance.” Suppression of emotion does diminish the expression of emotion but at a cost; it has deleterious effects for both the speaker and the listener. It doesn’t relieve or heal the underlying negative emotional experience; it consumes cognitive resources, impairs memory, and is associated with increased sympathetic activation of the cardiovascular system for both the suppressor and the person feeling the emotion.2 By shutting down expressions of emotion, even unintentionally, we lose the chance to help the speaker feel heard or to understand what underlies the emotion. Emotions can be a window into important concerns. In that sense, beyond an opportunity for building trust and connection, emotions are a thread clinicians can follow to better understand values, confusion, or commitments, and with that knowledge give the patient or family member what she or he most needs.

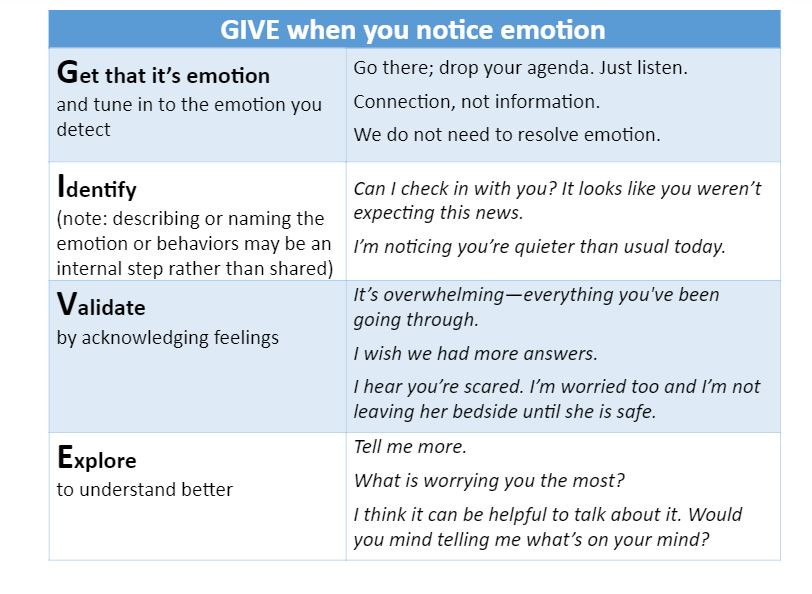

When we recognize and respond to emotion effectively, we create an alliance and a more productive interaction. When people feel heard and respected, they are more likely to be honest, and open to considering our advice. Paradoxically, when we address “emotion before cognition,” we actually shift the activity of the brain away from the more emotion-focused areas to areas responsible for reasoning and processing, such as the prefrontal cortex.3 In addition, emotion is critical to decision-making; 4 without acknowledging emotion, key data about what is important to the person is lost. One strategy to improve emotional interactions is to use the mnemonic G.I.V.E. (See below)

In many circumstances, pausing the conversation to show concern or caring through nonverbal gestures is enough. Some people prefer not to talk about their feelings, and what comforts one person might not be effective for another. For that reason, it is important to inquire, a component of the “explore” step of this approach. If challenged to recall the details of the mnemonic, simply remembering to “give” one’s attention and patience when emotion is present helps validate and promotes alignment and a space for sharing. Though this response to emotion often obviates the need for data or answers, there are times when providing information or data may be calming and productive. Listening to understand more deeply through acknowledging and exploring emotion will reveal that need.

In response to the scared patient before a procedure, we can do similarly:

“I hear that you are scared. It’s normal to be scared, it’s a big procedure. What worries you the most?”

And to the trainee who may be feeling overwhelmed:

“I hear you say you’re stressed and it’s overwhelming. That’s hard. Most of us feel stressed sometimes. Do you want to talk about it?”

We may feel we do not have time to “give.” However, it need only take a few moments to acknowledge and validate emotion. Those few words can build relationships, enhance trust, 5and allow greater comprehension and collaboration. 6 Empathy can improve health outcomes, and is under-recognized as a source of health influence.7 Emotion before cognition” incorporates the human need for empathy to diminish the intensity of emotion and to connect, build trust, think more clearly, and gain valuable insight.

Laura K. Rock is a Pulmonologist and Critical Care Physician at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts and an Assistant Professor at Harvard Medical School.

Competing interests: None declared.

References:

- October TW, Dizon ZB, Arnold RM, Rosenberg AR. Characteristics of physician empathetic statements during pediatric Intensive Care conferences with family members: a qualitative study. JAMA Netw Open.2018;1(3):e180351-e180351. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0351.

- Gross JJ. Emotion regulation: affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology.2002;39(3):281-291.

- Lieberman MD, Eisenberger NI, Crockett MJ, Tom SM, Pfeifer JH, Way BM. Putting feelings into words. Psychol Sci.2007;18(5):421-428. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01916.x.

- Lerner JS, Li Y, Valdesolo P, Kassam KS. Emotion and decision making. Annu Rev Psychol.2015;66(1):799-823. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115043.

- Halpern J. From idealized clinical empathy to empathic communication in medical care. Med Health Care Philos.2014;17(2):301-311. doi:10.1007/s11019-013-9510-4.

- Stewart M. Patient recall and comprehension after the medical visit. In: Lipkin MJ, Putnam SM, Lazare A, editors. The Medical Interview. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1995. p. 525-529. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-2488-4.

- Kelley JM, Kraft-Todd G, Schapira L, Kossowsky J, Riess H. The influence of the patient-clinician relationship on healthcare outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e94207. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0094207.

Funding

This work was supported by a Mapping the Landscape, Journeying Together grant from the Arnold P. Gold Foundation Research Institute.