Governments across the world are putting in place unprecedented measures to slow the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. These measures focus on social distancing—keeping people away from each other—including closing hospitality venues and shops, stopping mass gatherings, and in many cases requiring the population to stay at home except for essential journeys. The impact this is having on people’s lives, mental health, and livelihoods is substantial. Everything possible should be done to reduce the time over which such measures need to be in force, while still limiting the spread of the virus.

Despite our best efforts, some inter-personal contact is inevitable during this time, such as between members of the same household, or by key workers with caring responsibilities. A behaviour that could make a substantial difference in these and other contexts, and costs nothing, is avoiding touching the mouth, nose and eyes —what has been called the T-Zone.1

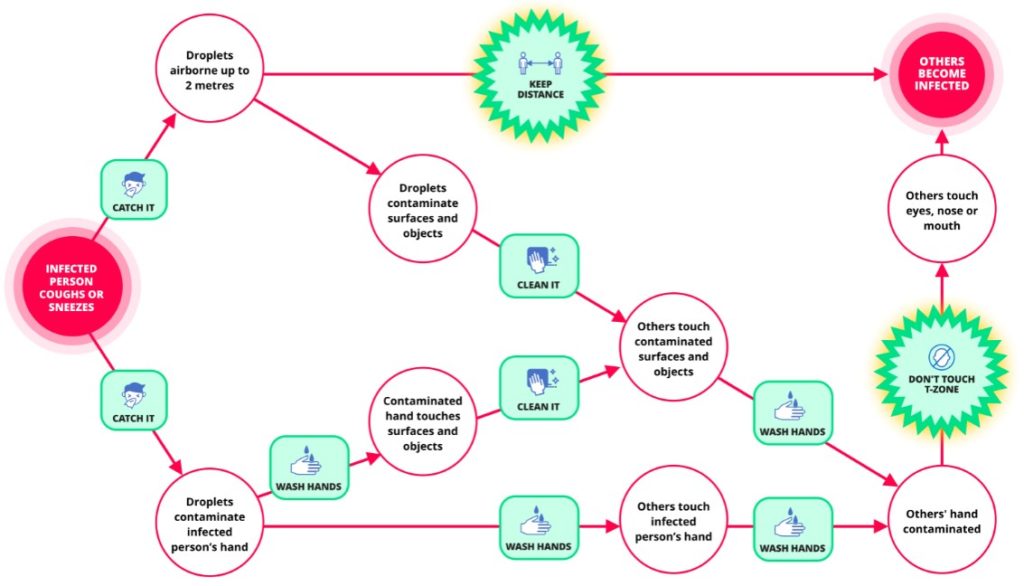

The primary route into the body for the virus is through the nose, eyes, and mouth. It enters cells of mucous membranes via ACE2 receptors.2 We have created the figure below to illustrate the fact that there are two ways in which the virus can come into contact with these membranes. One is by direct inhalation of droplets or aerosol and the other is by touching one’s mouth, nose or eye region with a contaminated hand or a contaminated object.

It is not known precisely how much transmission occurs by each route, but the latter can be expected to play a substantial role.3 This is because, while the virus is typically only airborne for a matter of minutes, it can contaminate surfaces and objects, known as ‘fomites’,3 for many hours and even days, and we are constantly touching these surfaces and objects. Washing hands and cleaning surfaces also play a crucial role, but keeping hands uncontaminated when there are so many potential fomites in our environment is extremely difficult and hand contamination only poses a problem if the hand then touches the T-Zone. It therefore makes logical sense to do everything we can to find ways of minimising this behaviour.

We wrote in an earlier opinion article about the more general behavioural strategies that can get people enacting protective behaviours.4 Given the crucial importance of this final pathway of touching the T-Zone it is absolutely vital to find ways of minimising this.

Considering its importance in infection control more generally, it is surprising how little evidence there is on T-Zone touching, but a recent study of medical students in Australia found that participants touched their face an average of 23 times per hour of which 44% involved touching a mucous membrane roughly evenly distributed across the mouth, nose and eyes.5 Two earlier studies, on small unrepresentative samples, found rates of face touching of 16 times per hour6 and 19 times per hour.1 We could find no trials looking at behavioural strategies to prevent this—not one! Such research is urgently needed but in the meantime, there are some first principles and anecdotal evidence which can help inform us.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that face touching occurs primarily under two conditions, unconsciously out of habit (including unconscious gestures), and consciously (to some degree at least) in response to an itch. These probably require somewhat different approaches to preventing their occurrence.

Habits can be controlled in a number of ways: 1) Train up a counter-habit that conflicts with, or redirects the impulse when the hands are travelling towards the face (e.g. directing the action to something else such as stroking one’s chin); 2) Put up behavioural barriers—doing things that make the habit physically difficult or impossible to enact (e.g. when in meetings, sitting with hands clasped together); 3) Put up physical barriers (e.g. by wearing something that prevents hands getting access to the key areas); and 4) Generate mindfulness—bringing the action to conscious awareness before it is completed (e.g. by putting a scent on one’s hands so that the aroma acts as a reminder as the hand nears the face).

Stopping oneself scratching an itch can seem surprisingly difficult. Itches evolved to make us scratch them.7 While there is some research into how to control itches caused by skin conditions, very little is known about strategies to stop oneself touching the affected area, whether medical8 or behavioural. There may be lessons from research into ways of controlling other types of urge, such as the urge to smoke.9

Behavioural strategies for coping with urges more generally have been classified under five headings under the acronym, DEADS: delay, escape, avoid, distract, substitute.10 How far each of these is likely to be effective to combat the urge to scratch an itch is not known but it seems a reasonable starting point. One might add others from a taxonomy of 93 behaviour change techniques that have been identified.11

It may seem strange that such a simple thing as not touching the T-Zone is so hard to do when so much is at stake, but failure to adhere to life-saving treatment regimens,12 and continuing to enact extremely harmful behaviours such as smoking13 tells us that humans are strange creatures.

To promote effective behavioural control requires a sound understanding of the capability, opportunity, and motivational factors involved14-16 and not just an appeal to common sense understanding.

Robert West, professor of health psychology, department of Behavioural Science and Health, University College London, UK.

Susan Michie, professor of health psychology and director of the Centre for Behaviour Change, University College London, UK.

Richard Amlôt, head of the Behavioural Science Team, Emergency Response Department Science and Technology (ERD S&T) at Public Health England, and visiting professor of practice in the psychology of health protection at King’s College London, UK.

G. James Rubin, Reader in the Psychology of Emerging Health Risks, King’s College London, UK.

Declaration of interests: None declared

Role of funding source: Michie is affiliated to University College London’s Centre for Behaviour Change and the National Institute for Health Research Behaviour Science Policy Research Unit. Amlôt is affiliated to the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit in Emergency Preparedness and Response at King’s College London, and Evaluation of Interventions at the University of Bristol, in partnership with Public Health England. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care or Public Health England. The funders played no role in the writing of the manuscript of the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- Elder NC, Sawyer W, Pallerla H, Khaja S, Blacker M. Hand hygiene and face touching in family medicine offices: a Cincinnati Area Research and Improvement Group (CARInG) network study. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine : JABFM. 2014;27(3):339-46.

- Fehr AR, Perlman S. Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ). 2015;1282:1-23.

- Kraay ANM, Hayashi MAL, Hernandez-Ceron N, Spicknall IH, Eisenberg MC, Meza R, et al. Fomite-mediated transmission as a sufficient pathway: a comparative analysis across three viral pathogens. BMC infectious diseases. 2018;18(1):540.

- Michie S, West R, Amlot R, Rubin G. BMJ Opinion, 2020. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/03/11/slowing-down-the-covid-19-outbreak-changing-behaviour-by-understanding-it/

- Kwok YL, Gralton J, McLaws ML. Face touching: a frequent habit that has implications for hand hygiene. American journal of infection control. 2015;43(2):112-4.

- Nicas M, Best D. A study quantifying the hand-to-face contact rate and its potential application to predicting respiratory tract infection. Journal of occupational and environmental hygiene. 2008;5(6):347-52.

- Andrews M. Why and how do body parts itch? Why does it feel good to scratch an itch? Scientific American. 2007.

- Andrade A, Kuah CY, Martin-Lopez JE, Chua S, Shpadaruk V, Sanclemente G, et al. Interventions for chronic pruritus of unknown origin. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2020;1:Cd013128.

- West R. The multiple facets of cigarette addiction and what they mean for encouraging and helping smokers to stop. Copd. 2009;6(4):277-83.

- Khoddam R. Psychology Today [Internet]2015.

- Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Annals of behavioral medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2013;46(1):81-95.

- Emamzadeh-Fard S, Fard SE, SeyedAlinaghi S, Paydary K. Adherence to anti-retroviral therapy and its determinants in HIV/AIDS patients: a review. Infectious disorders drug targets. 2012;12(5):346-56.

- West R. Tobacco smoking: Health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. Psychology & health. 2017;32(8):1018-36.

- Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a guide to designing interventions. London: Silverback Publishing; 2014.

- Michie S, Van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation science. 2011;6(1):42.

- West R, West J. Energise: The Secrets of Motivation. London: Silverback; 2019.