Lucy Yardley, Richard Amlôt, Cathy Rice, Charlotte Robin, and Susan Michie share strategies to enhance community engagement and cooperation during the covid-19 pandemic

Infection control measures based on restricting movement and interpersonal contact can be effective in slowing down the transmission of infection, giving healthcare systems more time and capacity to cope with covid-19. These measures will only be effective if as many community members as possible are able to implement them as fully as possible. As we enter the period of pandemic management that will require people to self-impose difficult restrictions on their activities, it is vital to understand how to engage and involve everyone in this communal effort.

Research on responses to public health emergencies has shown that people will cooperate to achieve common goals if they feel like they are part of a shared communal effort, and if they believe the people leading this effort are part of the same “community of circumstance” and are acting legitimately on their behalf. Providing clear, detailed information to justify recommended actions promotes trust that leaders and policymakers are acting in the common good, which increases motivation to support and engage with public health advice.

When people feel like they’re a valued part of a community effort, which they understand and support, they are also more likely to actively engage with helping others in the community. In the current pandemic, this type of community support for people who are moderately ill or self-isolating will be essential to the success of pandemic management.

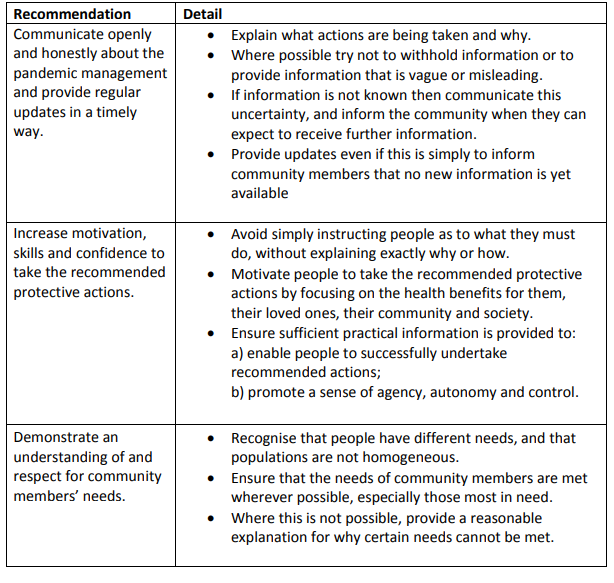

Communication strategies known to enhance community engagement and cooperation are shown in Table 1. Communicating effectively is a difficult task when the basis for action is complex, uncertain, and fast changing. Yet to ensure community engagement, it will be vital to show that the diverse needs of members of the community are understood and have been addressed as far as possible. For example, advice to “stay at home if ill” and “avoid all contact with people at high risk” will inevitably cause anxiety and anger if this instruction is simply impossible to implement because the symptomatic person is the sole carer for an at-risk family member they live with, or if they have no one to support them.

Table 1. Communication strategies to enhance community engagement and cooperation

Many people will have to make very difficult choices about how much contact they can and should risk with which people—particularly when they need to provide or receive important practical or emotional support. If people feel that they are not given enough information to allow them to undertake these difficult actions, or that their agency, choice, or control over their lives is undermined, then their sense of cohesion with the leaders and organisations providing guidance will be compromised. As a result, public health directives are more likely to be resented and inadequately applied or even ignored.

Anticipating and addressing the wide range of difficulties people are likely to face is a huge and urgent task, but not an insurmountable one if a “bottom-up” approach is adopted. Engaging with people from a diverse range of backgrounds can ensure that public health advice is quickly tailored and adapted to the many different contexts in which it will be implemented.

UK policymakers and providers are already employing rapid methods of evaluating people’s varying needs and experiences, using surveys, interviews, and focus groups to inform response efforts. For example, rapid interviews carried out by Public Health England with people now self-isolating have already suggested important ways in which this measure can be made both easier to achieve (by preparing “self-care” packs in advance) and less distressing (through daily phone contact).

Media and social media reactions often usefully highlight further questions and populations that need to be considered. The direct involvement of community members can also have an invaluable role, providing immediate feedback on how the advice and support offered can be made more accessible and appropriate to people in different situations. For example, community members are well placed to suggest and support realistic and constructive alternatives to face-to-face contact—and have recommended that these should be shared with people in similar situations.

The task of establishing a two way dialogue to ensure that advice to community members is relevant and helpful is not just the preserve of national policymakers. Advice on aspects of pandemic management will be provided by every healthcare organisation, and by employers, schools, universities, and many other institutions. All of these communications can be improved by demonstrating responsiveness to people’s views and needs. There are many methods to achieve this; for example, online panels and fora could directly inform rolling “question and answer” public-facing websites to address key questions and concerns in real time, while the “you said, we did” format can be used to demonstrate responsiveness to people’s views.

If the advice we provide is insensitive, impractical, or inconsistent with community members’ experiences, they can quickly tell us how it will need to be changed—but only if we fully engage with and involve them in our response efforts.

Lucy Yardley is a professor of health psychology at the University of Bristol and University of Southampton and a member of the Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Behavioural Science (SPI-B): 2019 Novel Coronavirus (Covid-19).

Richard Amlôt is the head of the Behavioural Science Team, Emergency Response Department Science and Technology (ERD S&T) at Public Health England, and visiting professor of practice in the psychology of health protection at King’s College London.

Cathy Rice has undertaken public involvement in a wide range of health research since surviving a stroke.

Charlotte Robin, Field Epidemiology, Field Service, National Infection Service, Public Health England, and Health Protection Research Unit in Evaluation of Interventions.

Susan Michie is a professor of health psychology and director of the Centre for Behaviour Change, University College London.

Competing interests: None declared.

Role of funding source: Yardley is affiliated to National Institute for Health Research Applied Research Collaboration West at University of Bristol and Biomedical Research Centre at University of Southampton.

Amlôt is affiliated to the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit in Emergency Preparedness and Response at King’s College London, and Evaluation of Interventions at the University of Bristol, in partnership with Public Health England.

Michie is affiliated to the National Institute for Health Research Behaviour Science Policy Research Unit at University College London.

The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care, or Public Health England. The funders played no role in the writing of the manuscript of the decision to submit it for publication.