There are many strategies to change people’s transmission-related behaviours as a method for flattening the peak of the epidemic

As we move into the “delay” phase of managing the covid-19 epidemic, changing people’s transmission-related behaviours across society as a method for flattening the peak of the epidemic becomes more urgent. [1,2]

Changing behaviour is not easy. However, there are many strategies to help people change behaviour that focus on increasing motivation, capability and/or opportunity to perform the behaviours. [3,4] Here we focus on strategies that improve motivation or capability.

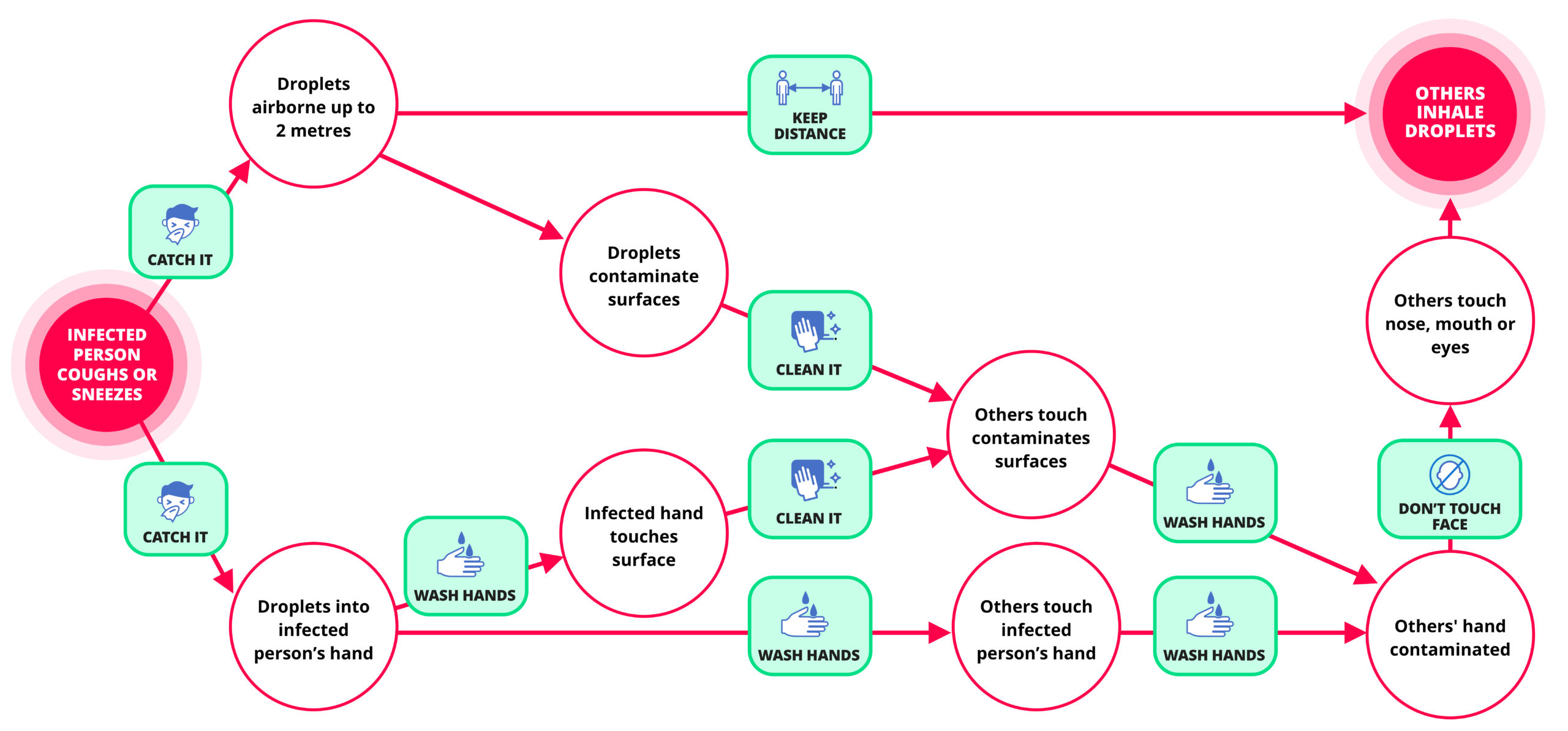

Behaviour change principle 1: Create a mental model. One way of motivating people is to make sure they have an accurate mental model of the process of transmission that provides a strong rationale for what they need to do to prevent it. [5] The figure below shows such a model. It shows how the virus gets into the environment and is then inhaled, and how its route to transmission can be blocked at various points in the journey by protective behaviours.

Figure: A mental model of how to block transmission of the virus

Behaviour change principle 2: Create social norms. People are social beings—we are strongly motivated by what others think about us. This was nicely demonstrated by a study of the use of soap dispensers in the toilets of motorway service stations: the more people there are in the washbasin area, the more that people washed their hands. [6] The same study found that, despite people reporting that they regularly wash their hands, soap was used by 65% of women entering the toilet area and only 32% of men. Norms can be created by media campaigns targeting people’s self-identity and getting people to give each other feedback.

Behaviour change principle 3: Create the right level and type of emotion. Emotion is a powerful driver of behaviour, but it is a double-edged sword. Two emotions that are important in getting people to take appropriate protective action are anxiety and disgust. Giving disgust-related messages has been found to be particularly effective for men, who appear to have most “room for improvement” in this regard. [6] Although a degree of anxiety about the health threat is helpful in making recommended behaviours more likely, too much anxiety is counterproductive—resulting in either unnecessary behaviours or defensive avoidance that mininises the perceived threat. [7,8] To avoid both of these it is important to couple all anxiety-provoking messaging with actions that people can do to protect themselves. [9]

Behaviour change principle 4: Replace one behaviour with another. We need to stop people touching their nose, mouth, and the area around the eyes. Research suggests we touch our faces more than 20 times per hour on average. [10] This is largely automatic and difficult to stop. Rather than just telling people not to do it, we can increase their ability to do it by telling them about another behaviour they can do that conflicts with it. In this case it could be “Keep your hands below shoulder level”

Behaviour change principle 5: Make the behaviour easy. Unless the challenge of the behaviour is part of its attraction, people are more likely to enact behaviours the easier they are do. There are many ways to make things easier. One important one is to build it into an existing routines. The less people have to change in their existing current routines to incorporate recommended behaviours, the more likely they are to occur. For example, people can be advised to check that they have tissues on them when they are also checking that they have their house keys.

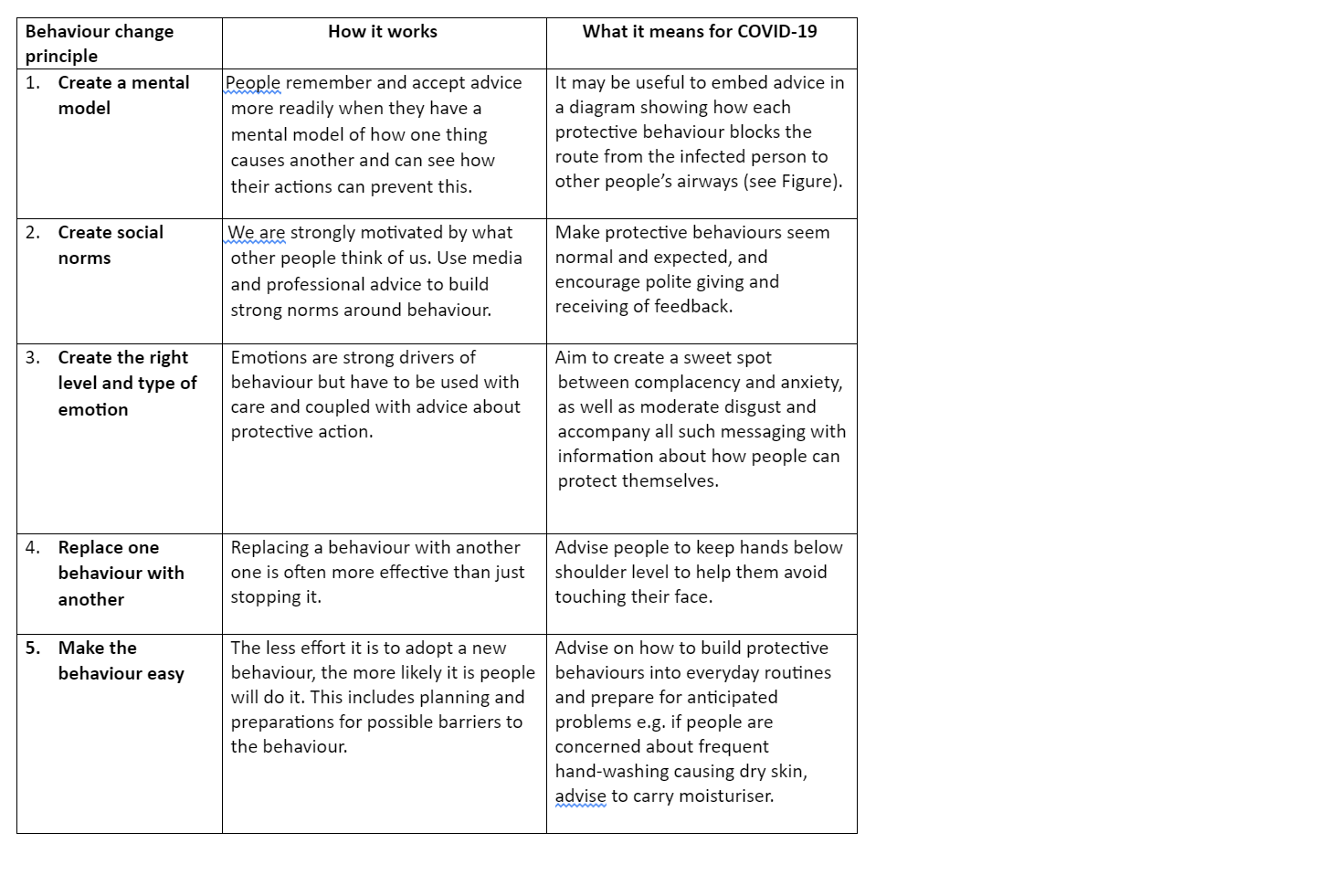

The Table below summarises five principles of behaviour change relevant to slowing down the spread of covid-19. These should help doctors and all those in a position of influencing the behaviours of patients, the public and, indeed, themselves.

Table: Five principles of behaviour change and their application to delaying the spread of COVID-19

Susan Michie is Professor of Health Psychology and Director of the Centre for Behaviour Change at University College London and a member of the Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Behavioural Science (SPI-B): 2019 Novel Coronavirus (Covid-19).

Robert West, professor of health psychology, department of Behavioural Science and Health, University College London.

Richard Amlôt is the head of the Behavioural Science Team, Emergency Response Department Science and Technology (ERD S&T) at Public Health England, and visiting professor of practice in the psychology of health protection at King’s College London.

James Rubin, Reader in the Psychology of Emerging Health Risks, King’s College London.

Competing interests: None declared

References:

-

- Michie S, West R & Amlôt R. Behavioural strategies for reducing COVID-19 transmission in the general population. BMJ Opinion, March 3rd 2020.

- Michie S, Rubin GJ & Amlôt R. Behavioural science must be at the heart of the public health response to covid-19. BMJ Opinion, February 28th 2020.

- Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The Behaviour Change Wheel: a new method for characterizing and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science. 2011; 6: 42. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-6-42.

- Michie S, Atkins L, West R. (2014) The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions. London: Silverback Publishing. www.behaviourchangewheel.com.

- Leventhal H, Nerenz DR & Steele DJ. (1984). Illness representations and coping with health threats. In Baum A, Taylor SE & Singer JE (Eds.), Handbook of psychology and health (Vol. 4, pp. 219–252). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Judah G, Aungur B, Schmidt W-P, Michie S, Granger S, Curtis V. Experimental pretesting of hand-washing interventions in a natural setting. American Journal of Public Health. 2009; 99: 405-411.

- Rubin GJ, Potts HWW, Michie S. The impact of communications about swine flu (influenza A HINIv) on public responses to the outbreak: Results from 36 national telephone surveys in the UK. Health Technology Assessment. 2010;14(34):183-266 doi:10.3310/hta14340-03.

- Croyle RT, Sun Y-C & Hart M. (1997), Processing risk factor information: Defensive biases in health-related judgments and memory. In Petrie K & Weinman Ja. (Ch. 9). London: Routledge. doi.org/10.4324/9781315078908.

- Peters G-JY, Ruiter RAC, Kok G. Threatening communication: A critical re-analysis and extension of meta-analyses to determine the behavior change potential of threatening health information. Health Psychol Rev. 7(Suppl. 1) S8–S31. doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2012.703527

- Kwok YL1, Gralton J1, McLaws ML2. Face touching: a frequent habit that has implications for hand hygiene. Am J Infect Control. 2015 Feb;43(2):112-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.10.015.

Declaration of interests: None declared

Role of funding source: Michie is affiliated to the National Institute for Health Research Behaviour Science Policy Research Unit at University College London. Rubin and Amlôt are affiliated to the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit in Emergency Preparedness and Response at King’s College London, and Evaluation of Interventions at the University of Bristol, in partnership with Public Health England. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care or Public Health England. The funders played no role in the writing of the manuscript of the decision to submit it for publication.