A 90 year old woman near the end of her life is hoisted from a hospital bed, semi-conscious, for staff to take a photo of the pressure sore on her bottom. Two hours later, her husband arrives on the ward to find that she has died.

How did we end up here? When looking through healthcare records, why is it more normal to see photos of pressure ulcers on backsides than photos of faces?

This patient had been taken to the hospital that morning because staff felt it was unsustainable for her to stay at home. She’d become weaker over the past few weeks, and developed incontinence. Her husband, also 90, found this hard to manage. She knew that she was dying, and we knew that she preferred to stay at home. But somehow the system didn’t seem able to support that. Her needs weren’t particularly specialist or complex, but somehow admission to hospital seemed like the least worst option from the perspective of the nurse visiting her.

In their 90 years, this couple hadn’t used the health service very much. When they did need it, we fell short. Despite everyone involved caring deeply—from the nurse who arranged to take her to hospital, the paramedics who wanted to set up a drip en route, the ward nurse who took the photo, the regulator who wants care to be above all safe and to protect people from avoidable harm—and despite everyone doing their best to do their job—we let this couple down.

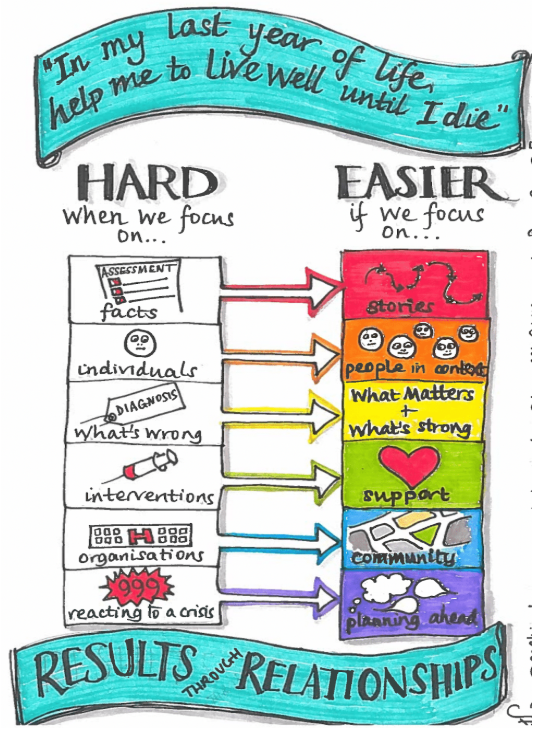

Looking at their story, and stories of others in different circumstances, we saw that there are predictable patterns that explain our tendency to (more often than we’d like) miss what matters. We can tend to focus on facts rather than stories; services and organisations rather than community; interventions rather than support; reacting to a crisis rather than planning ahead. This all makes it harder to support people well, particularly in the last months of life.

Of all our lifetime healthcare costs, a third is spent in the last year of our lives. Healthcare costs—particularly hospital costs—rise dramatically in the last weeks of life. With stories like this, it’s easy to see why this may happen. Care which focuses on tasks—rather than what matters—costs more overall, and tends towards outcomes that no-one wants.

We can do better than this.

We can create a world in which it’s normal to ask each other and talk to each other about what really matters to us. We can give each other the time, knowledge, confidence, freedom and support to respond in highly bespoke ways to the people and circumstances we find. And we can make it normal to find out and do what matters most to a patient rather than just what’s expected.

Creating that world may not always be easy and will take some courage. It will mean stopping doing some of the things we do now, some of the things which we have become accustomed to doing and that may make us feel safe. For the patient we described above, this would mean the chance to stay at home on the last day of her life, and for her husband to be with her when she died—even though the circumstances were not as we had anticipated. It would mean being able to rest in comfort rather than being hoisted to have a photo of her pressure sore—recognising that her dignity and comfort were more important than following the “standard protocol.” It will therefore mean not only challenging the ways we care for the people, families, and communities we support but also the way that we care for each other within our institutions. Only then may we feel like doing what really matters is doing what really matters here.

What really matters to you?

Saskie Dorman, Consultant in Palliative Medicine, Forest Holme Hospice, Poole Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. @saskie_dorman

Andy Brogan, Founding Partner, Easier Inc. @AndyTBrogan @Easier_Inc

This work is part of Results through relationships, improving personalised care towards the end of life: Dorset Integrated Care System in association with NHS England Personalised Care Group, with coaching and facilitation from Easier Inc. With thanks to everyone who has contributed to this work.

Reference:

Georghiou T and Bardsley M (2014) Exploring the cost of care at the end of life. Nuffield Trust.