Carl Heneghan and Jeffrey Aronson take a closer look at a recent lung cancer screening trial

The Dutch Belgian Randomized Lung Cancer Screening (NELSON) Trial has recently reported reductions in lung cancer survival but not overall survival. The interpretation of results from screening trials is problematic and often gives rise to major uncertainties.

The NELSON trial is the second-largest study of low-dose CT screening for lung cancer; it randomised 13,195 men and 2594 women at high risk of lung cancer to four rounds of screening (uptake was 95% in year 1, falling to 77% after 6.5 years of follow-up).

What did they find?

In all 22,600 CT scans were performed, of which 467 were positive; 203 of these proved to be detectable lung cancer (positive predictive value 44%). Screening detected some cancers at an earlier stage than would have been if there had been no screening: 59% of the screen-detected lung cancers were at stage 1, compared with 13% in the non-screened group.

There was an excess of 40 cases of lung cancer (344 vs 304) among the men who were screened – the authors reported this as a suggested excess-incidence overdiagnosis rate of 20% (95% confidence interval (CI) −5 to 42).

The reported cumulative rate ratio for death from lung cancer at ten years of follow-up was 0.76 (95% confidence interval 0.61 to 0.94). Among women, the rate ratio was a non-significant 0.67 (95% CI 0.38 to 1.14). In the paper, Table 4 reports the causes of death for the men who died; all-cause mortality was not affected by screening, with a rate ratio of 1.01 (95% CI 0.92 to 1.11).

Several biases and possible imbalances between the groups should be considered when interpreting these results. Potential biases include lead-time bias, slippery and sticky diagnosis bias, and competing risks bias. Those being screened may have been encouraged by their participation to review their smoking habits, potentially leading to small but important imbalances in risk factors between the groups (only 2 year follow up data has so far been reported). The significant increase in deaths attributed to causes other than lung cancer meant there was no reduction in all-cause mortality. For example, deaths from endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases were more than doubled in the screened group, rate ratio 2.34 (95% CI 1.03 to 5.80). This also suggests an imbalance between the groups, since it is not clear why screening should increase the risk of such diseases.

What do the results show?

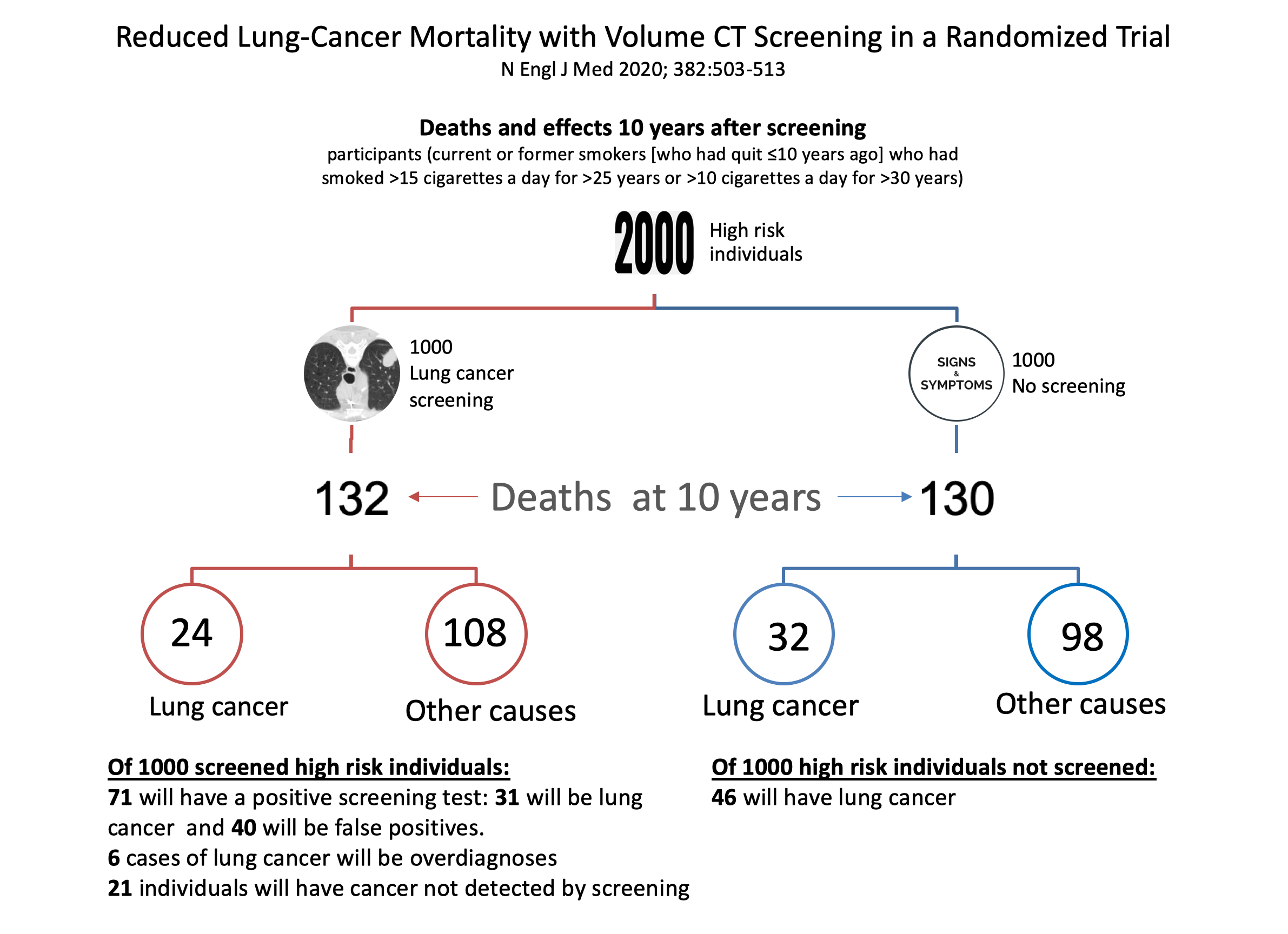

It isn’t easy to understand and interpret the results of screening trials such as NELSON, as they are currently reported. Part of the reason for this is the different ways in which results are reported statistically across screening trials (e.g. as rate ratios, cumulative rate ratios, or odds ratios, per person-years at risk, and different reported durations of risk). A better way to understand the data is to present the results per 1000 screened (see below figure).

In a sample of 2000 people at high risk of lung cancer, of 1000 screened, 132 will die at ten years compared with 130 of the 1000 not screened. Of 1000 undergoing screening, 24 will die of lung cancer compared with 32 of the non-screened subjects (this is the quoted relative reduction of 0.76). However, 108 will die of other causes in the screening group compared with 98 in the non-screened group (relative rate 1.09; 95% CI 0.99 to 1.21).

Of the 1000 screened individuals 71 will have a positive test, of whom 31 will have lung cancer detected (a positive predictive value of 44%), and there will be 40 false positives, wrongly suggesting the presence of lung cancer. Six of those with detectable lung cancer will not have symptoms or die of the disease (the quoted overdiagnosis rate of 20% in the paper); and 21 individuals in the screening group will have cancer not detected by screening.

The other largest trial, the US National Lung Screening Trial (NLST), randomized 53,454 current and former smokers to screening with low-dose CT or chest x-ray once a year for 3 years. After an average of 6.5 years, 18 of 1000 individuals who received low-dose CT died of lung cancer compared with 21 who had had a chest x-ray (a similar 20% reduction to NELSON).

What can we conclude?

Screening for any disease should lead to better results, particularly in terms of mortality, morbidity, emotional wellbeing, and quality of life. The desire to detect disease earlier and earlier can stifle the debate of whether there are critical differences in outcomes that warrant screening.

Reductions in lung cancer mortality rates and a shift to earlier detection of disease create considerable pressures to implement lung cancer screening. We should, however, pause before considering implementation, because of the lack of effect on all-cause mortality in NELSON, the problems of false positives and overdiagnosis, potential biases, the substantial resources required, and the economic costs.

The decision to implement lung cancer screening will probably come down to a value judgement based on principles and beliefs about whether screening is good or bad. It is therefore essential that policymakers and the public are better educated and informed about the benefits and harms of screening programs.

BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine publishes original evidence based research, insights and opinions on what matters for health care. (Instructions for authors)

Carl Heneghan is the Editor in Chief BMJ EBM and Professor of EBM, Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine in the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford

Carl Heneghan is the Editor in Chief BMJ EBM and Professor of EBM, Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine in the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford

Jeffrey Aronson is a physician and clinical pharmacologist working in the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine in the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford. He is an Associate Editor of BMJ EBM and a President Emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Jeffrey Aronson is a physician and clinical pharmacologist working in the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine in the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford. He is an Associate Editor of BMJ EBM and a President Emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: CH has received expenses and fees for his media work. He holds grant funding from the NIHR, the NIHR School of Primary Care Research and the NIHR Oxford BRC. CH is also Director of CEBM, which jointly runs the EvidenceLive Conference with the BMJ and the Overdiagnosis Conference with international partners, based on a non-profit making model. JA none declared.

Reference:

de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, de Jong PA, et al. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Volume CT Screening in a Randomized Trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(6):503–513. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911793