According to a recent research paper published in JAMA, four cohorts of 252 745 women showed no “statistically significant association” between the use of talcum powder in the genital area and ovarian cancer. The evidence base for talc, its association with cancer, and the current reporting present a practical case to discuss observational evidence and some confusions with the understanding of harms.

Many early talc products were cross-contaminated with micro-deposits of asbestos, mined from the same locations. In 1976, voluntary US guidelines asked US manufactures to ensure talc products were free from detectable asbestos. Since, there has been controversy over the risk of using talc in the genital area, with lawsuits asking whether it causes cancer. Other countries have permitted talc potentially containing asbestos to be mined and used, adding to concerns.

The latest evidence

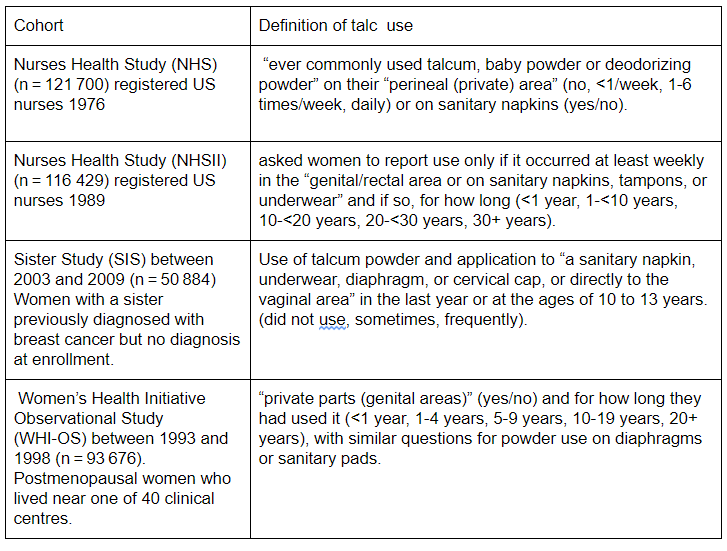

Four US based cohorts assessed the use of powder in the genital area and followed women to see if they developed incident ovarian cancer. The four cohorts differed in their populations, years of recruitment, ascertainment of exposures and in their definition of use: 39% reported ever use, 22% frequent use and 10% long-term use (see the Table below).

The two Nurses Health Studies questionnaires did not initially ask about genital use of powder: participants were asked post hoc and no studies collected data on the use of talc after baseline. Outcomes were self-reported, but the accuracy of ascertainment was improved through the use of medical records, national death index searches, and pathology reports.

In the 257 044 women, 2168 developed ovarian cancer. The results reported that ovarian cancer incidence was 61 cases per 100,000 person-years among ever users, and 55 cases per 100,000 person-years among never users, Hazard ratio 1.08 (95% CI, 0.99 to 1.17). Additional findings included frequent versus never use, HR 1.09 (95% CI, 0.97-1.23); and long-term versus never users, HR 1.01 (95% CI, 0.82 to 1.25).

The media reporting

The research received widespread attention: “Big study finds no strong sign linking baby powder & cancer,” said the Washington Times; “The truth about talcum powder and cancer,” the Telegraph. Many of the 120 news outlets that ran with the story reported no link between talc and ovarian cancer.

The NHS Behind the Headlines service reported there was “no evidence that talcum powder causes ovarian cancer.” What this report and many others did, though, was fail to place these new findings in the context of pre-existing research.

In 2016, Behind the Headlines reported that researchers had found a significant link between genital talc use and ovarian cancer—”an increase in risk of a third, compared with no use.” Although they advised caution in interpreting the results as they were based on small sample sizes. The Daily Mail reported, “Risk of disease is ONE THIRD higher for women who use talcum powder on their genitals, experts warn.”

To add to the confusion, the 2016 case-controlled study these results were taken from—reporting the increased risk—included participants from the Nurses’ Health Study as cases.

More recently, a systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of perineal Talc and Ovarian Cancer identified 24 case-control studies (13,421 cases) and three cohorts (890 cases). The review found that any perineal talc use was associated with an increased risk of ovarian cancer, OR = 1.31 (95% CI = 1.24 – 1.39). This effect was significant in the case-control studies but not in the cohort studies. However, for cohorts, there was a significant association for invasive serous type ovarian cancer.

What we can we conclude

Using all the available evidence aids the assessment of harms, particularly when outcomes are rare. Because none of these studies were set up to ask about talc and incident cancer, there will always be limitations such as recall bias, reporting bias, confounding and differences in the questionnaires that affect the interpretation of the results. With rare events, and at best moderate evidence, it will prove difficult to definitively conclude whether talc is associated with ovarian cancer. In this situation, a balanced probability approach—used by the law—can be helpful: based on the best available evidence is the occurrence of the event more likely than not?

Interpretation of isolated studies rarely proves helpful. To arrive at an informed decision requires all the evidence; the approach could facilitate more balanced media reporting and aid public understanding.

Table of the four studies and definitions

BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine publishes original evidence based research, insights and opinions on what matters for health care. (Instructions for authors)

BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine publishes original evidence based research, insights and opinions on what matters for health care. (Instructions for authors)

Carl Heneghan is the editor in Chief BMJ EBM, Professor of EBM, University of Oxford and will be speaking at EBM Live, Getting Better with Evidence, on the 10th December in New Zealand on the implications of the mesh judgment.

Acknowledgement: I would like to thank Jeff Aronson for helpful comments and edits.

Competing interests: CH has received expenses and fees for his media work. He holds grant funding from the NIHR, the NIHR School of Primary Care Research and the NIHR Oxford BRC. He has received financial remuneration from an asbestos case and given free legal advice on mesh cases, and received income from the publication of a series of toolkit books published by Blackwells. On occasion, he receives expenses for teaching EBM and is also paid for his GP work in NHS out of hours. He is Editor in Chief of BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine, clinical advisor to the APPG on Surgical Mesh and an NIHR Senior Investigator. CH is also Director of CEBM and Programs in EBHC CEBM jointly runs the EvidenceLive Conference with the BMJ and the Overdiagnosis Conference with some international partners based on a non-profit model.

References:

- Association of Powder Use in the Genital Area With Risk of Ovarian Cancer. JAMA. 2020 Jan 7;323(1):49-59. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.20079.

- Perineal Talc Use and Ovarian Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Epidemiology. 2018 Jan;29(1):41-49. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000745

- The Association Between Talc Use and Ovarian Cancer: A Retrospective Case-Control Study in Two US States. Epidemiology. 2016 May;27(3):334-46. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000434.