The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) not only defines words. It gives variant spellings, etymologies, and instances of their uses in quotations from printed texts. And it does so, as the original rubric had it, “on historical principles”. In all cases it gives as the first instance of the use of a word the earliest example that the lexicographers have found. They do a stunningly good job, finding early instances of words in the most recondite places and checking their sources obsessively.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) not only defines words. It gives variant spellings, etymologies, and instances of their uses in quotations from printed texts. And it does so, as the original rubric had it, “on historical principles”. In all cases it gives as the first instance of the use of a word the earliest example that the lexicographers have found. They do a stunningly good job, finding early instances of words in the most recondite places and checking their sources obsessively.

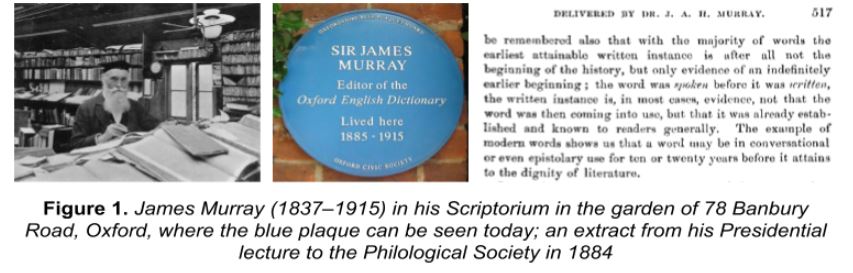

However, even the most assiduous search for a word may miss an earlier example, an antedating, to use the technical term. The editor of the first edition of the OED, James Murray (Figure 1), estimated that about three-quarters of its headwords could be antedated. He also pointed out, in a Presidential lecture to the Philological Society in 1884, that words are generally spoken before they are written down, so that written sources will generally postdate the date of invention or introduction of a word.

In 1978 Richard W Bailey published about 4400 “Additions and Antedatings to the Record of English Vocabulary”. He described the collection as “not a definitive or complete listing of antedatings and additions to the OED but a provisional collection sufficiently coherent to be of general use to scholarship”. Here is a medical example: “femur” is not only the name of a bone in the body, the earliest example of which dates from 1666, but also an architectural term, defined in the OED as “any of the flat, vertical, projecting faces between each pair of glyphs of a Doric triglyph”, dating from 1563. But Bailey gives an example of the anatomical use taken from John Skelton’s 1485 translation of Bibliotheca Historica by Diodorus Siculus, written between 36 and 30 BC: “he apprepred unto this montuous place a name and called it femur as moch to say in oure barbarian language as a thye.”

The late Jürgen Schäfer’s Survey of Monolingual Printed Glossaries and Dictionaries 1476–1640 was published posthumously in 1989 in two volumes, the second of which contained a long list of additions and corrections to the OED, some of which have still not been incorporated. For example, “diaphoretic” is currently defined as “having the property of inducing or promoting perspiration” (they mean “sweating”; first quotation 1563) or “a medicinal agent having this property” (first quotation 1656). But Schäfer gave a quotation from 1526, found in an anonymous glossary of medical terms, The grete herball: “Dyaforetyke is whan a medycyne spredeth humours and vapours insencyble whiche be mynysshed in suche maner, meued and made in so subtyll vapour that it voydeth without noyaunce”.

It is no coincidence that the texts cited by both Bailey and Schäfer were written in Early Modern English, which is usually dated from about 1476, when Caxton started printing, to 1700, encompassing works by such writers as Shakespeare, Spenser, Jonson, Donne, and Milton.

However, it is important to remember that in James Murray’s day searching had to be done by hand, reading original texts and noting down instances that might be useful. Today, digitized texts can easily be searched for specific words, and the earliest instances quoted in the dictionary are therefore less likely to be antedatable. Nevertheless, antedatings are still possible. I have been searching for antedatings of words that are first recorded in the OED for years ending in 20 and 70, in the same way that I chose medical anniversaries in 2020 to highlight last week. Here are some examples, all involving words whose first attested examples come from 1920.

The OED gives the earliest instance of “lymphadenopathy” in a paper in the Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital from 1920, but there is an earlier instance still, from 1915 (Wade HW. Bacteriemia due to Bacillus diphtheriae. J Infect Dis 1915; 16(2): 292-302); this is a minor antedating, and although it is possible that an earlier instance might be found, it would be unlikely to antedate these instances by very much.

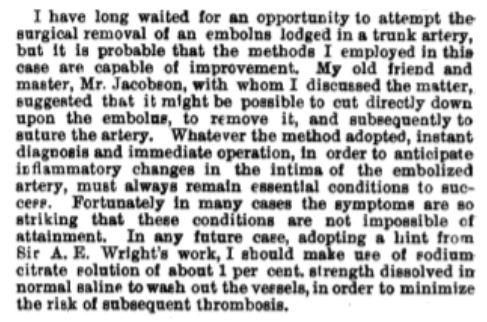

The OED gives the earliest instance of “embolized” from a 1920 article in the Quarterly Journal of Medicine, but an earlier instance, from 1907, can be found in the British Medical Journal, in an article by W Sampson Handley, Hunterian Professor in the Royal College of Surgeons, titled “An operation for embolus” (21 September 1907; 2(2438): 712).

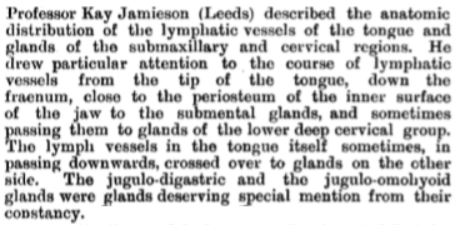

Another example from the British Medical Journal antedates two words listed as first having been recorded in 1920 in the British Journal of Surgery, “jugulodigastric” and “jugulo-omohyoid”; both appear in the issue of 14 August 1914.

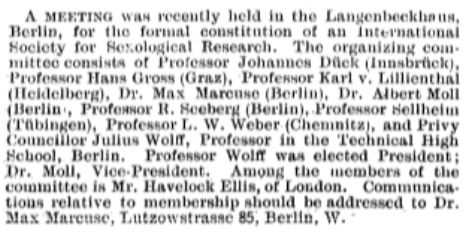

That The BMJ may be a rich source of antedatings is suggested by the next example. “Sexological” is first attested in the OED in a quotation from 1920, but the British Medical Journal contains an example from 1913, in which the formation of an International Sexological Society is described.

According to the OED, “spermiogenesis” was first recorded in 1920. But in 1912, the American zoologist Thomas Harrison Montgomery published a book titled Human spermatogenesis, spermatocytes and spermiogenesis: a study in inheritance. The OED defines spermiogenesis as “the maturation of spermatids into spermatozoa (the last phase of spermatogenesis)”, which explains why it is differentiated from spermatogenesis in the title of Montgomery’s book.

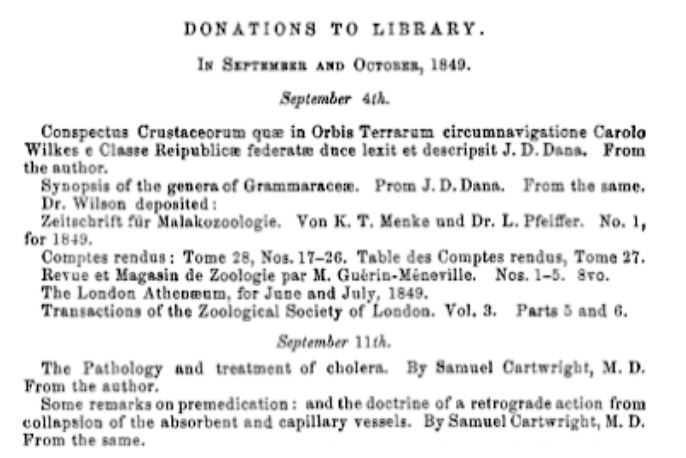

A striking antedating, but a less sure example, is “premedication”, also dated by the OED from 1920. It means the administration of a medicine to produce sedation or other useful effects, such a drying of secretions, before an operation, or a medicine so used. I have found a much earlier example of this, from 1849, in the title of a book by Samuel Cartwright: “Some remarks on premedication: and the doctrine of a retrograde action from collapsion of the absorbent and capillary vessels”. This title is to be found in a list of donations to the library of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia in the Academy’s proceedings, published in late 1849.

However, it is by no means clear in what sense Cartwright used the term “premedication”, and since I have not been able to locate a copy of his book I cannot be sure that this is a true antedating. It could of course be a completely new meaning of the word, or even a typographical error. Further investigation is necessary. Perhaps the Academy in Philadelphia, now the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, still has a copy.

Some lexicographic anniversaries in 2020

1520 (131):

flex (a joint or limb)

insensate

meselness (leprosy)

sanguineous

1570 (868):

doctoral

doctorly

medicus

poorly

1620 (412):

atrophy

cardiacal

cardialgic

coarctate

deoppilate (blocking, e.g. a vein)

depressive

dietetical

excrete

flaccid

gustative

ingestion

morbifical (causing disease)

plague spot

scammoniate (purgative)

vomitory

1670 (357):

alcoholize

antiapoplectic

blue pill

bronchotomist

dagga (hemp, Cannabis sativa)

[Dr] Goddard’s drops

hygiastic

insufflate

neurology

osteology

pancreatical (pancreatic 1666)

pharmacopoietic/al

quackish

sclerotis (the sclera)

semiotics (interpretation of symptoms)

1720 (178):

fetification (impregnation)

unrespirable

1770 (219):

molecular

kairomone

Lassa [fever, virus]

l[a]evodopa

Mandy (i.e. Mandrax)

maprotiline

mazindol

medicaliz/ation

myelographic (myelogrphy 1937)

metabolizer

mianserin

migraineur

1820 (575):

aegophony

arteritis

coelia

daturia (the alkaloid daturine)

epicranial

feticide

ovario-gestation

phrenological (phrenology 1810)

plague ship

rheumatismal

rubeoloid

somatological (somatology 1736)

stethoscope

1870 (753):

abiogenesis

acridine

acrocephaly

agoniadin

anapnograph

anginiform

asystolism (= asystole)

biogenesis

carbolize

cryptopine (an opium alkaloid)

Duchenne [paralysis]

electrosurgery/ical

epicritic [remarks on a case]

excitomotor

germicide/al

glioma/tous

idiot savant

innervate

intertrochlear

leucocyte

mesethmoid

methaemoglobin

micrococcus

monocephalic

muscularis

odontoblast

oecoid

orchidectomy

paedology

parasitology

pedicurist

periodontitis

phthinode/oid

pleuroperitoneal

polyuric (polyuria 1823)

prepubic (prepubis 1888)

pseudoleukaemia

minoxidil

monounsaturated

mucolipidosis

myelinotoxicity

myoelectrical (myoelectricity 1969)

neuraminate

neuroplasticity

neuroregulator

nexin

oncornavirus

peptidolytic (peptidolysis 1972)

recipiomotor

Romberg [symptom]

spectroscopy

subanconeal

thoracico-abdominal

1920 (466):

Acetobacter

acidotic (acidosis 1900; acidaemia 1891)

Alexander [technique]

bacteriocyte

bibliotherapy

biotechnologist

cardiothoracic

electromyographic (electromyography 1926)

embolized (adj)

haemorrhage (v; noun 1671)

heterophile

hypnoanalysis

jugulodigastric

jugulo-omohyoid

lymphadenopathy

megaunit

moniliasis

multifactorial (= polygenic)

myelinogenetic (myelinogenesis 1931)

nasospinale

periodontist

pluripotential

premedication

premorbid

psychopharmacology

radiosensitivie

self-diagnose

sexological (sexology 1867)

sociobiologist

spermiogenesis

swine influenza

1970 (373):

alloalbumin

ancrod

arenovirus

biocompatible

bioequivalency

bioethics

biofeedback

clastogen

clonazepam

immunodiagnostics

immunosurveillance

perimenstrual

prazosin

psychoneuroendocrinology

ribostamycin

sulfazin

sulpiride

temazepam

tilorone

togavirus

tretinoin

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.

| This week’s interesting integer: 256

256 is the smallest non-trivial 8th power = 28, where “non-trivial” means other than 1. It is also the fourth number in the sequence of numbers raised to their own power: 1 = 11 4 = 22 27 = 33 256 = 44 Thus, in analytic combinatorics 256 is the fifth in the sequence of numbers of labelled mappings from n points to themselves: 1, 1, 4, 27, 256. 256 is 100000000 in binary and 100 in hexadecimal. 256 is the traditional number of cycles per second (hertz) of middle C (called scientific pitch). However, modern concert pitch is usually modelled on a frequency of A above middle C at 440 Hz, making middle C 261.6 Hz = 440/29/12, since an octave doubles the frequency and has 12 well-tempered semitones, middle C being 9 semitones below A. |