As I reported last week, of about 60 words listed in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) beginning with thym-, only two refer to the mind, thymoleptic and thymopathy.

As I reported last week, of about 60 words listed in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) beginning with thym-, only two refer to the mind, thymoleptic and thymopathy.

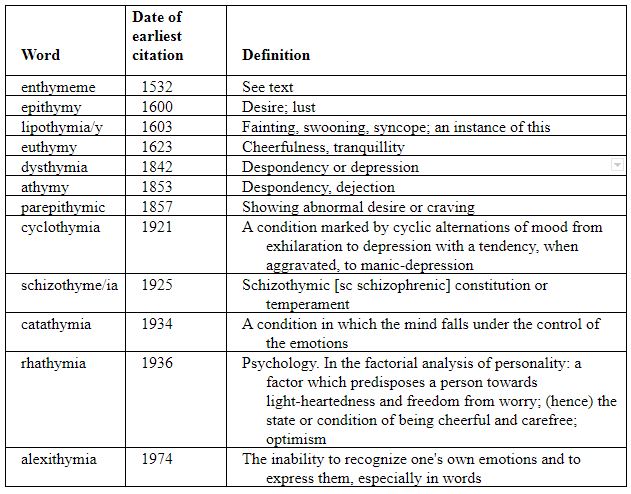

However, there are several words in which the mind is indicated by -thym- as an infix or by the suffix -thymia or -thymy and derivatives such as -thymic and -thymically (Table). In all of these words, the -thym- element derives from the Greek word θυμός, mind, and in each case the derivative reflects some state of mind, be it related to cheerfulness, depression, desire, or the effects of emotions. There is, however, an exception, enthymeme.

The Greek verb ἐνθυμεῖσθαι, derived from the prefix ἐν, in, and θυμός, the mind, meant to think, consider, or infer. A related noun, ἐνθύμημα, meant thought or an argument or piece of reasoning; Aristotle regarded an enthymeme as a type of dialectical argument, a “body of persuasion”, i.e. its main constituent, specifically a rhetorical trope drawn from premises that were only probable, not proven. A syllogism typically has two premises, major and minor, and a conclusion based on them. An enthymeme typically has only one premise. Aristotle subdivided enthymemes into two types: those based on probabilities and those based on signs. The acceptability of the conclusion depends on acceptance of the premise—either that something is sufficiently likely to happen or that the signs really exist. For example:

Premise: He has a fever. Conclusion: He is ill.

Acceptance of the existence of the sign (the fever) implies the conclusion.

In Latin, the word became enthymema, a thought or concept. Cicero used it to mean an antithesis ending a piece of rhetoric, giving as an example, in De Topica, “Can you fear this man, and not fear that one?”.

“Enthymeme” then entered English in the early 16th century, when logicians used it to mean a deductive argument having a proposition that is not explicitly stated, and specifically a syllogism with an unstated premise. The OED gives an example: the syllogism “All cats are mammals; therefore all lions are mammals”, is an enthymeme, because the minor premise, “All lions are cats” is unstated, being implicitly true. One 16th century logician, Abraham Fraunce, writing in Lawiers Logike (1588), was not impressed: “An enthymeme is nothing but a contracted syllogism”. It was also later suggested that in Descartes’ famous enthymeme “I think therefore I am” the missing minor premise was “thinking exists”.

Enthymemes work when the missing premise is correct. However, when the premise is incorrect the conclusion will be wrong. Medical errors sometimes occur because a premise is mistakenly assumed to be correct. Here is an example.

Major premise: People with ventricular extra beats after a myocardial infarction have an increased risk of sudden cardiac death.

Conclusion: Use of the antiarrhythmic drug flecainide will reduce the risk of sudden cardiac death.

The major premise is correct, but the conclusion is wrong. The missing minor premise may not be obvious:

Minor premise: An antiarrhythmic drug will suppress serious extra beats without any adverse effects of its own, thereby reducing mortality.

It is the missing minor premise, which turns out to be unpredictably misguided, that leads to the false conclusion. In the placebo-controlled Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST) both flecainide and encainide increased mortality in people with ventricular extra beats after a myocardial infarction. Proarrhythmic effects of antiarrhythmic drugs are now well-known.

The error was to believe, as cardiologists at first did, that the minor premise, which assumed an unproven underlying mechanism, was true, rather than a hypothesis in need of testing. It is likely that before it was tested many people died because of the use of antiarrhythmic drugs in this way, which has been estimated to have led to more deaths than among US soldiers killed in wars such as those in Korea or Vietnam. The story has been told by Thomas J Moore in his book Deadly Medicine.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.