Wherever our patients are, they should all have the same opportunities to take part in research, says Cheng-Hock Toh

Tomorrow morning, two patients with the same medical condition and needing the same treatment will wake up in different hospitals.

Tomorrow morning, two patients with the same medical condition and needing the same treatment will wake up in different hospitals.

The first patient, Morgan, wakes up in a well funded large teaching hospital in the middle of England. This hospital undertakes a lot of research, is involved in large scale clinical trials and international collaborative research, and has no shortage of high quality candidates for consultant posts. The doctor in charge of Morgan’s ward has won international prizes, led successful bids for research funding from the Medical Research Council (MRC) and Wellcome, and is chair of the relevant international society.

Another patient, Robin, wakes up in a small district hospital on the coast of England. This hospital does not undertake much research, is not involved in clinical trials or international collaborations, and has difficulty recruiting. The doctor running Robin’s ward is one of a series of four locums the hospital has employed over the past two years. This doctor is overworked, rarely has time to go to educational or specialty society meetings, and has not instigated any research either at this hospital or in any previous locum posts.

While neither Morgan nor Robin are themselves the subject of research, Morgan will receive better care and have a better outcome simply as a result of being in a research active setting. In other words, we are failing patients by allowing research to concentrate in specific geographical areas.

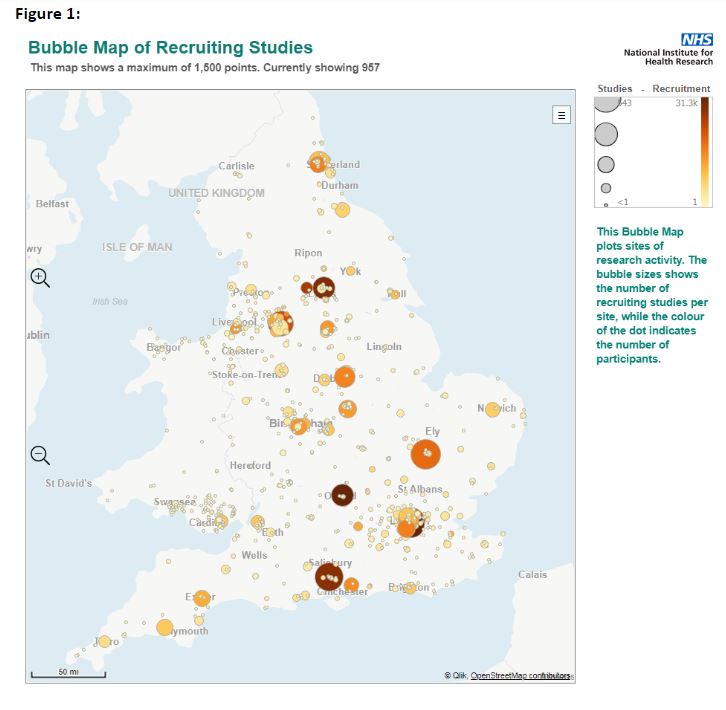

The graph from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) illustrates the situation perfectly, and will hold no surprises for anyone involved in research in the UK. It demonstrates neatly the concentration of research into centres based around medical schools and large university hospitals. However, instead of accepting that this is the case and should continue, I believe we should be challenging this status quo at every turn. Otherwise we are failing patients who live outside those research active centres.

How did we arrive at this situation?

The research landscape in the UK is complex. It is not centrally managed and is historically characterised by a mix of public and private (including pharmaceutical sector funding) and diverse organisational arrangements. The UK has never had an all encompassing national medical or healthcare research strategy. Several bodies including the NIHR, the MRC, NHS England, and Public Health England have their own research strategies, and it is part of the NHS Constitution and the trust inspection remit of the Care Quality Commission.

Until relatively recently, the strategies of bodies like the NIHR and the MRC have concentrated on the clinical research areas to be funded and the demonstrable quality of the outcomes. This has favoured “big ticket” multi-centre studies, or Nobel prize winning novel drug or metabolic mechanism discoveries. Medical journals perpetuate the “big is beautiful” model, and as guardians of public money, research bodies can’t really be blamed for awarding big grants to previously successful researchers and pre-existing research units or collaboratives with a great track record, thus perpetuating the situation. No one would want to denigrate or lose the UK’s astonishing track record in groundbreaking clinical research. Yet it certainly isn’t helping to spread the research load and its consequent patient benefits from the centres to the periphery, so we need to find alternative solutions.

Although NHS trusts are a recognised body in terms of applying for MRC grants and many pay lip service to research in their mission statements, very few know what their R&D strengths are, so it’s not surprising that few of those unconnected to a university apply for research funding. In addition, the concentration of research into the main centres means that research on certain medical conditions isn’t always carried out near the largest patient populations with those conditions. This can often lead to a disconnect between the researcher, their subject area, and the patient population most affected, so those areas, their hospitals, and consequently their patients fail to benefit from the increased focus.

NIHR has recently made great strides in encouraging and supporting the outlier NHS trusts to take part in more research, and encouraging partnership projects between experienced research centres and smaller hospitals. However, clinicians in these peripheral hospitals are often not equipped with the resources and protected time that are a given for the larger centres. We know from the survey that the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) carried out in 2017 that doctors have reduced time for research, although a high percentage want to do it.

As someone who has been involved in research in the NHS for many years, I know that there are not just real practical barriers, but sometimes unspoken barriers. In a hard pressed department, it can be awkward to ask senior colleagues for more protected time, or for the existing protected time to be just that—actually protected. Research sometimes gets stuffed into the one and half programmed activities available for correspondence, reviewing notes, and consulting with colleagues, until it isn’t protected at all. I’ve known trusts welcome research proposals that bring in money, but when that money then goes directly to the trust and not the department organising the research, researchers don’t necessarily feel appreciated.

So what should we do?

As doctors, we should change the national conversation and recognise that research in the NHS is everyone’s responsibility and a core part of clinical care. Every doctor should be research active, whether this is identifying opportunities for new research, recruiting patients, supporting colleagues, or leading trials themselves. And that means a much broader definition of research, including audit and quality improvement. Sometimes the answers we are looking for are staring us in the face from the rich data that we already have on the day to day care of our patients.

We should be proactive in seeking opportunities for our patients to be involved in research and seek development opportunities to equip ourselves with research skills. As the professional body for physicians, the RCP will support clinicians in building the confidence and research skills to be credible partners in research. Look at research as a way of doing something different that increases job satisfaction and in turn retention. Use what influence you have to push your trust into making research a core activity.

If you or your trust are not directly involved in research or quality improvement, what could you do after reading this article—send it to a colleague, suggest you get together over a coffee to discuss a potential research project? Do you know a colleague or trainee who would really like to do some research but needs support? If you are already involved in research, could you reach out to colleagues in hospitals that are not? We all can and should do something to ensure that wherever our patients are, they all have the same opportunities to take part in research and benefit from it.

Cheng-Hock Toh is a professor and consultant in haematology in Liverpool. He is the academic vice-president for the Royal College of Physicians London, national specialty lead for haematology in the National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Network, and president of the British Society for Haematology. Twitter @CHToh1

Competing interests: None declared.