Esteriek de Miranda and Jeroen van Dillen

In the Netherlands there are strong and opposing opinions among healthcare providers about the optimal time to induce labour in otherwise low risk pregnant women. The Cochrane review on “Induction of labour for improving birth outcomes for women at or beyond term” does not help because only one of the studies included in the review, which had a limited sample size, compared induction at 41 weeks with expectant management until 42 weeks.

As the uncertainty regarding the management of late, term pregnancy was considered the most important evidence gap in the management of term pregnancies, the INDEX-study was prioritised by the professional organisations of both midwives and gynaecologists in the Netherlands. Despite this, we still faced challenges when conducting this trial in daily practice.

We came across different opinions within and between professional groups regarding the optimal management. Similarly, the preferences of eligible pregnant women regarding the desired management strategy in late term pregnancy also varied, which hampered inclusion in our trial.

The birth culture in the Netherlands is rather down to earth: women consider pregnancy and childbirth to be normal physiological phenomenons in which it is preferable for nature to take its course. This was reflected in the large number of women who refused to participate in the trial because they preferred a policy of expectant management in their low risk pregnancy. We also had to accept that there were caregivers who preferred not to counsel women to participate in the trial due to their own preference for induction or expectant management. Consequently, it took us more than a year longer than we expected to reach the required sample size. Overall, it took us six years from the conception of the study to the birth of our research paper.

But have we solved the management problem now once and for all? Not in the way that we presumed we would. As we expected, we found that women had a high chance of a good outcome in both groups, although with a small difference in overall adverse perinatal outcomes favouring induction of labour at 41 weeks. The absolute risk of clinically relevant adverse outcomes, however, was low in both groups.

Does this justify a change in the management strategy of late term pregnancy towards induction at 41 weeks? With the results of our study, the discussion among caregivers about when to start induction of labour in uncomplicated late term pregnancy will probably continue; balancing statistical significance and clinical relevance. Considering the great impact of earlier induction on women’s individual experience of childbirth and on birth culture in general, the evidence would need to be convincing to justify a change in clinical practice.

In our view, the data from our study can be used by pregnant women to make a reasonable choice about the management strategy in late term pregnancy that best suits their own preferences, risk perception, and way of life, which can be either induction of labour at 41 weeks or expectant management until 42 weeks.

We are still waiting for a more individualised approach that can help us distinguish between women who can safely await spontaneous onset of labour, and women who would benefit from earlier induction.

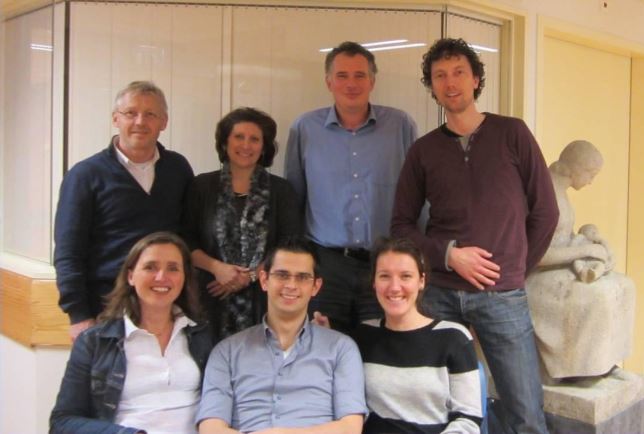

The “INDEX core team” in the start-up phase of the trial

From left to right in front: Judit Keulen (midwife, PhD student), Joep Kortekaas (resident O&G, PhD student), Aafke Bruinsma (midwife, PhD student), from left to right behind: Frank Vandenbussche (professor obstetrics & fetal medicine), Esteriek de Miranda (midwife, assistant-professor, INDEX-project leader), Ben Willem Mol (professor obstetrics & gynaecology), Jeroen van Dillen (gynaecologist, perinatologist)

Esteriek de Miranda, project leader INDEX-trial, Amsterdam UMC-University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Jeroen van Dillen, perinatologist, co-team leader INDEX-trial, Radboudumc, Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

Competing interests: See linked research paper.