My last two pieces have dealt with dragons and rings, two topics that merge in legend.

My last two pieces have dealt with dragons and rings, two topics that merge in legend.

The word “dragon” comes from an IndoEuropean root DERK, to look at. From this came the Greek verb to look at, δέρκεσθαι, whose aorist tense, ἔδρᾰκον, I looked, gave δράκων, a monster possessed of the evil eye, a dragon. Another monster whose look was fatal, the basilisk (Greek βασιλίσκος, literally a little king), or cockatrice, was supposedly hatched from a cock’s egg by a serpent. And δράκων, interchangeable with ὄϕις, also meant a serpent. Both δράκων and ὄϕις could also mean a serpent-shaped ring, bracelet, or necklace.

When Cadmus, who founded Thebes, married Harmonia, her mother Aphrodite gave her a necklace. Roberto Calasso described it in Le Nozze di Cadmo e Armonia (The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony): “It was a snake, studded with stars, with two heads, one at each end, mouths wide open, facing each other. But neither mouth could bite the other, for caught between their teeth were two golden eagles, wings outspread, forming a clasp.”

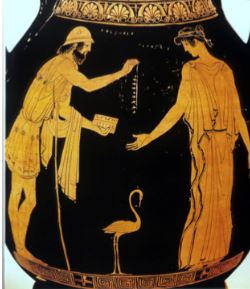

In one version of the myth, the god Hephaestos forged the necklace and gave it to his wife Aphrodite, imbuing it with evil powers, in retribution for her adulterous affair with Ares, Harmonia’s father. It brought ill luck to all who possessed it. Jocasta supposedly wore it when she married her son Oedipus. Their son Polynices inherited it and gave it to Eriphyle (picture), as a bribe to persuade her husband Amphiaraus to join him in the fight to regain Thebes from Eteocles, Polynices’ brother. All three died in the battle, as Aeschylus described in his play Seven Against Thebes. Alcmaeon, son of Amphiaraus, acquired the necklace, killed his mother for having persuaded his father to join Polynices, and himself went mad.

Polynices gives Eriphyle Harmonia’s necklace, as depicted on a red-figure amphora of around the 5th century BC. The presence between them of a bird is a puzzle; Liddell & Scott’s Greek Lexicon says that δρᾰκοντίς is a type of bird, but doesn’t specify which type; perhaps it’s the one in the picture?

According to Ovid, Cadmus left Thebes as a troubled old man and went wandering with Harmonia. When they reached Illyria he reflected on the dragon of Ares he had slain so many years before and attributed his ill luck to the gods’ vengeance. He prayed that he might be turned into a serpent, and as he prayed both of them were transformed.

A δράκων was also a wand with a snake twined round it, like the symbol that Eric Gill incorporated in his logo for the BMA, which used to adorn the front cover of The BMJ.

Rings and dragons guarding stolen treasures feature in various myths. In Richard Wagner’s opera Das Rheingold, the dragon Fafner (Fafnir in the original Norse myth) guards a treasure, stolen from the dwarf Alberich, which contains the Tarnhelm, a magic helmet, and the ring of the Nibelungs that gives its name to Wagner’s cycle of four operas, Der Rings des Nibelungen, starting with Das Rheingold. J R R Tolkien’s dragon in The Hobbit, Smaug, a “most specially greedy, strong and wicked worm”, who guards the dwarves’ stolen treasure, is based on Fafnir, and Bilbo’s conversation with him in Chapter 12, while wearing the ring of invisibility, echoes Fafnir’s dying conversation with Sigurd (Siegfried), who kills him.

The Latin word draco meant a snake, often a sacred guardian of a treasure. It was also applied to various mythical monsters and to describe a hardened vine and an apparatus with spiral tubes used to heat water. Draconitis was a precious stone, taken from a dragon’s head. And dracontion and dracunculus (a little snake) were names for plants with snake-like roots, such as Arum dracunculus. In postclassical Latin dracunculus became dranculus, which in Anglo-Saxon became rauncle, a festering sore or abscess, such as a snake bite might cause. Hence our modern word rankle, which originally mean to fester, putrefy or rot, or to inflict a festering wound, later to poison, embitter, or inflame, and then simply to annoy persistently, irritate, or rile, to feel hurt or bitter, or to cause such feelings.

Dracontion, Arum dracunculus, may have been confused with Artemisia dracunculus, a plant of the wormwood genus, commonly called tarragon, which reportedly has “anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, and antihyperglycemic effects”, although no clinical applications have emerged. Medieval terms for the plant included the Italian dragontéa, Spanish taragontia, and French serpentine. So there is a possible connection with dragons.

To chase the dragon, place heroin on a piece of tinfoil, heat it, and inhale the fumes, which undulate on the foil like the tail of the mythical Chinese dragon. But beware spongiform leukoencephalopathy. Perhaps Harmonia’s dragon-like necklace continues to exert its curse.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.