Here’s a word that isn’t to be found in any English dictionary, as far as I can tell, “nihilitis”.

I have previously discussed the numerous ramifications of the IndoEuropean root NE, “not”, from which many negative Latin, Greek, and English words derive (Table 1). Here are some Latin derivatives, just those beginning with n: ne (lest, or so that not), nec or neque (nor), nefas (an offence or sacrilege), negare (to naysay), nemo and nullus (no-one), neuter (ne uter, not either), nil and nihil (nothing), nisi (unless), non (not), num (surely not?), and nolle (to want not to, willy-nilly). Nepenthes, a Greek nickname for Apollo (νή πένθος = no pain or sorrow), gives us the opioid nepenthe.

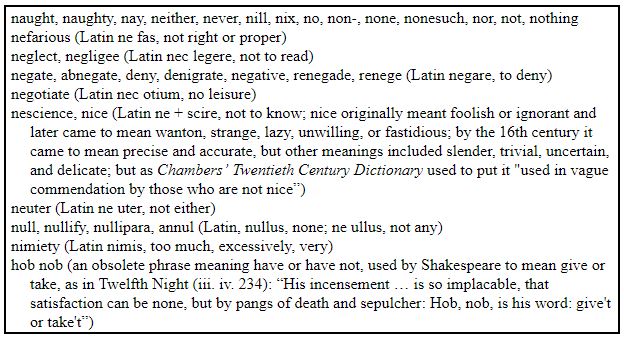

Table 1. Some English words derived from the IndoEuropean root NE, via Latin

Many English words begin with the Latin word “nihil”, nothing: nihilagent (a person who does nothing), nihilarian (a person who deals with things of no importance), nihilate (to annul), nihilation (a non-existent thing), nihileity, nihility, or nihilhood (the quality or state of being nothing; non-existence, nullity), nihilification (the action of disregarding something; slighting; valuing at nothing), nihilify (to disregard; to take no account of), nihili-parturient (producing nothing), nihilism (total rejection of prevailing religious beliefs, moral principles, laws, etc), nihilist, and nihilistic. Some words have nihil in the middle, such as transnihilate, unannihilation, annihilate and its many derivatives, and floccinaucinihilipilification.

All of these are in the Oxford English Dictionary, but not nihiliscient, which Anthony Burgess invented in Napoleon Symphony (1974), nor “nihilitis”, which combines the negative NE with the common inflammatory suffix –itis, which I have also discussed before.

Nevertheless, “nihilitis” exists in medical texts. The earliest instance of which I am aware is in an 1886 Lancet article about paying for hospital services:

“One advantage may indeed be claimed for the paying system by way of reducing the attendances of chronic cases where treatment is of no avail, and perhaps in choking off a class of ailments pretty universally recorded as nihilitis.”

What those ailments were is not recorded, but the wording suggests that “nihilitis” was a familiar word and that earlier instances may be found. Indeed, it is also to be found in The History of Addenbrookes Hospital (CUP, 1991), citing data from 1884-8.

The word continued to appear in medical texts in the first three decades of the 20th century (Figure 1). Here is an example from The BMJ, in an anonymous 1905 annotation titled “Practice in Labrador”, citing an article by Dr Wilfred Grenfell in Leslie’s Monthly:

“Late one evening a fisherman came off to our vessel, a shy sort of fellow. … ‘Are you a doctor, sir?’ he asked; ‘I want bleeding, please, sir.’ To ease his mind I called him below to examine him. Finding, however, it was only a case of impure blood, without any symptoms, and having no patience to spend time on nihilitis, I dismissed him unbled and turned in.” [The man persisted and Grenfell finally gave in.] “‘You see, sir,’ he said, while the operation was going on, ‘an old Indian squaw, she bled my feet a good spell ago, and I haven’t had ne’er a pain since. So when they told me there was a doctor aboard, I thought it was a good chance.’ But he added, half regretfully, ‘it didn’t feel quite the same. She bored the holes with a kind o’ corkscrew.’”

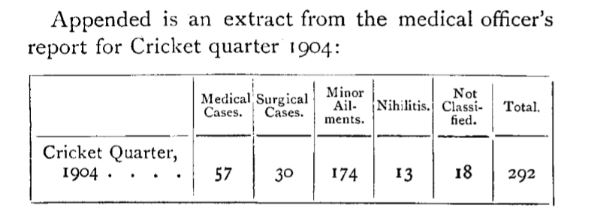

Figure 1. An extract from Charterhouse (2nd edition) by AH Tod. London: G Bell and Sons, Ltd, 1919; similar tables are to be found in editions of the St. Thomas’s [sic] Hospital Reports (1915, 1923, 1929, 1931) and the Westminster Hospital Reports (1929) [Thanks to Des Devitt for drawing my attention to the history of Charterhouse School]

Grenfell’s account was also reported in an issue of The Christian Advocate (1905; 80: 51), under the heading “Bleeding a fisherman”.

“Nihilitis” also occurs in German texts, where we can read about “nihilitis acuta”, nihilitis chronica”, “nihilitis crepitans”, and “nihilitis reservica”. Ervin Liek, in The Doctor’s Mission: Reflections and Revelations of a Medical Man (John Murray, 1930) wrote that “[German] colleagues of mine, highly experienced in panel practice, tell me that two-thirds of the activities of panel doctors are superfluous. In Poland, where social insurance is flourishing, the disease statistics have a special column of cases superscribed ‘nihilitis’.”

“Nihilitis” also survives in the polyglot English/French/German Dictionary of Environmental Protection by Otto and Ingrid Tutzauer (Heymann, 1979).

I define “nihilitis” as “any supposed medical condition that needs no treatment”. A word that we might find some use for today, perhaps.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.