I’m still spooked when I walk through the portal of St Mary’s Hospital Paddington. Memories of my patient journey through the hospital’s intensive care and high dependency wards remain vivid. But they were soon dismissed when I returned there recently to participate in a James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership meeting. The day proved all absorbing as twenty invited participants—a mixed bunch of patients, carers, and health and social care professionals—hotly debated priorities for research to improve the safety of care for adults with complex health needs.

I’m still spooked when I walk through the portal of St Mary’s Hospital Paddington. Memories of my patient journey through the hospital’s intensive care and high dependency wards remain vivid. But they were soon dismissed when I returned there recently to participate in a James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership meeting. The day proved all absorbing as twenty invited participants—a mixed bunch of patients, carers, and health and social care professionals—hotly debated priorities for research to improve the safety of care for adults with complex health needs.

The meeting was organised by the National Institute for Health Research Imperial Patient Safety Translational Research Centre and led by Katherine Cowan, senior advisor to the James Lind Alliance. She started the day by running us through the form of “JLA PSP” meetings. Over the past fourteen years the Alliance’s methods of setting “Top 10” priorities for research have been well honed and their approach adopted in several other countries.

In the UK the Alliance teams are recruited, trained, and funded by the National Institute for Health Research and Cowan underlined why it sees patient and public involvement in setting the research agenda as so important.

“The views of the people who live with medical conditions, and those who treat and care for them provide crucial insights into people’s needs, preferences, and priorities. “Getting their perspectives on key issues and questions to address in research is crucial, “and they tend to be very different from those of researchers and funders,” she said.

Our brief was to whittle down an already established list of 23 research questions to a top 10 via a “nominal group” technique. The questions which had been collected, analysed, and refined came from two previous surveys of around 450 patients, carers, and health and social care professionals with experience of living and dealing with complex and long term medical conditions. The list of questions was circulated to participants in advance with a request to rank them in importance. We were also reassured that they had been “checked against current evidence” and had not been answered already.

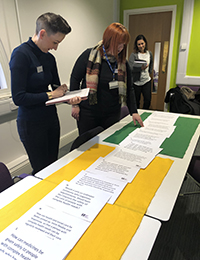

On the train on the way up to the meeting I had a go at ranking the questions. It was difficult, and I rapidly got distracted, not to mention irritated, by the ambiguous framing and terminology of a few of the questions. Two hours into the day as we gazed at long tables sporting large cards with the questions printed out on them I was convinced we would never agree on a top 10, let alone rank them in order of importance.

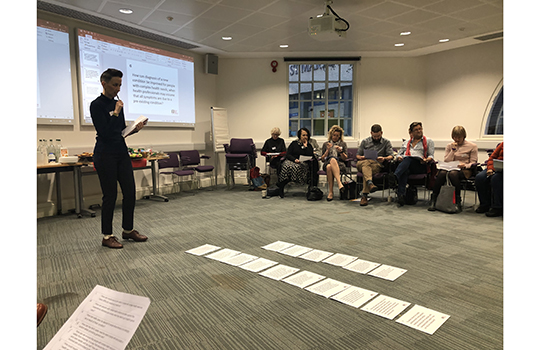

We were split into small groups, and we got to know each other, learn about each others’ lives, backgrounds, training, views, and experience of healthcare. It seemed as if we had been handpicked to be as disparate as possible. No doubt we had. And it was evident that each of us harboured strongly held views on how to improve patient care, which we were not about to relinquish readily.

Left to our own devices I suspect we would have caved in to the loudest among us.

But we were kept in check. All participants were encouraged and given sufficient time to articulate their views. Unsurprisingly, many of the most thoughtful observations and logical arguments on the importance of the issues that the questions addressed, came from the more retiring among us.

As we listened to each other and moved question cards up and down tables, there was a slow, but steady move towards consensus. Differences turned out to be more apparent than real. We found we mostly agreed on the fundamental things that help or hinder patients and carers from coping with complex conditions, and navigate (equally complex) health and social care services. There was even more consensus on where care currently falls short.

As we listened to each other and moved question cards up and down tables, there was a slow, but steady move towards consensus. Differences turned out to be more apparent than real. We found we mostly agreed on the fundamental things that help or hinder patients and carers from coping with complex conditions, and navigate (equally complex) health and social care services. There was even more consensus on where care currently falls short.

The most challenging task was to respond to a final invitation to make the group change their mind about the value of a question we personally held dear, but had not made the cut into the top 10. The spirited did their best and were listened to politely, but none were deemed to have produced arguments robust enough to drop one of the already identified “top 10” questions.

But what of the questions? It was refreshing to me to see the focus on how care is delivered, not the myriad treatments and interventions patients with multiple and complex long term medical conditions undergo. For patients and carers whose lives have been made more stressful than they need to be as a result of poor communication between health professional teams and organisations it was good to see this topic ranked high too. Seeing the patient as a whole person, not a collection of pathologies, also got emphasis. But as we left the meeting we were sworn to secrecy on the “top 10” questions which, we were told, were embargoed until early January. For the curious—and I hope you are, the veil has now been lifted.

Efficient and timely moderating of meetings is an under-rated skill. By the end of the day the Alliance facilitators got a round of applause for running a masterclass. We had succeeded in our objective and learnt valuable lessons on the reward of deep listening and maintaining respect for those whose views differ from our own. If an award was to be won for expert wielding of an iron fist in a velvet glove, I’d nominate them for it.

Efficient and timely moderating of meetings is an under-rated skill. By the end of the day the Alliance facilitators got a round of applause for running a masterclass. We had succeeded in our objective and learnt valuable lessons on the reward of deep listening and maintaining respect for those whose views differ from our own. If an award was to be won for expert wielding of an iron fist in a velvet glove, I’d nominate them for it.

Tessa Richards, The BMJ. You can follow her on Twitter @tessajlrichards

Competing interests: None declared.