The urgency to find systemic solutions to tackle the root causes of poor air quality is clear

I am convinced clinic room three is smokier than clinic room two. Although I have an N95 respirator mask in my bag, I don’t wear it because it feels a bit hypocritical to try to protect myself if I cannot give a mask to the patient sitting in front of me. So I just hold my breath when I go into clinic room three. This is the first time I have ever felt simultaneously worried about my own health, the health of my patients, and the safety of my children—whose school has just closed because the air outside is too dangerous to breathe.

This was the experience of one of the authors (EL), but illustrates what many healthcare professionals across California have been dealing with these past few weeks.

Wildfires continue to devastate California this week, leaving over 80 people dead, 1,000 missing, and thousands displaced. [1] Millions more are affected by the smoke blowing southeast from the worst fire in California’s history, as Northern California becomes the most polluted region in the world. [1]

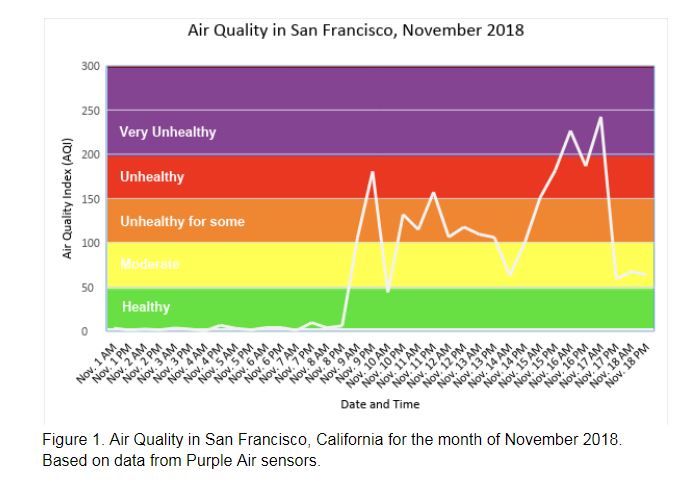

Air pollution is defined as the presence of a substance in the air that can cause harmful effects, and is measured by the Air Quality Index (AQI). An AQI of 0-50 is considered healthy air, while 151-200 is unhealthy for all. Ranges above 200 are considered very unhealthy, and above 300 hazardous. [2] The AQI reached as high as 271 in San Francisco on Friday—the worst air quality ever recorded in the city (Figure 1). [3]

Air pollution, including pollution due to wildfire smoke, has both immediate and long-term impacts on health. The immediate symptoms include wheezing, coughing, eye irritation, asthma exacerbation, and severe respiratory distress. [4] Children, older adults and those with preexisting respiratory disease are particularly at risk. [5] Air pollution also contributes to heart disease, stroke, lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and acute respiratory infections among children. [6] In addition, wildfires can have a significant impact on mortality. For example, smoke from the 2017 fires in Chile caused 76 premature deaths, and approximately 340,000 deaths each year are estimated to be due to landscape fire smoke. This increase in mortality can be significant even from short-term exposure. Indeed, a systematic review and meta-analysis of 108 studies examining short-term exposure (i.e. a few days) to high levels of air pollution found strong evidence of increased mortality and hospitalization among the elderly (0.64%, 95%CI 0.50-0.78) and a higher risk of death per 10 μg/m3 increase of particulate matter. In addition, this systematic review found evidence which suggested that women and those with lower socioeconomic status may be at higher risk of death following short-term exposure to air pollution.

Our community’s reaction to the polluted air has been mixed. Many Bay Area residents scrambled to find indoor air purifiers and N-95 respirator masks—both of which sold out from Amazon and local stores within one day. Many families with the means to travel left the area altogether, driving to the mountains or flying out of state. As doctors and health professionals we were prepared for the expected rise in emergency room visits, especially among the elderly, yet we have been largely unprepared to give advice or support to those patients who don’t have the luxury to leave or avoid being outdoors. [7]

“At least we don’t live in Beijing” one friend said. Another commented that “the air is always like this in India”. These statements point out our striking privilege as Californians—our air quality is expected to improve in a matter of days, and stay healthy in the long term. This is not true for the vast majority of people around the world. According to the World Health Organization, 91% of the world’s population live in areas with unhealthy air, and an estimated 4.2 million premature deaths occur each year due to outdoor air pollution. [8] Low- and middle- income countries are significantly more affected, and air quality disparities within and between countries continues to grow. [9,10] Over the past week air quality have reached levels that many Bay Area residents have found unbearable, but these levels are a daily reality for many other communities. Inequalities persist even within the United States, where air pollution varies significantly by race and socioeconomic status (SES), with people of color and those at lower SES exposed to the highest levels of particulate matter. [11]

As climate change leaves communities around the world increasingly vulnerable to drought, fire, and resulting air quality emergencies, doctors and health professionals cannot afford to simply treat patients suffering from acute exposures or recommend masks and air filters. The urgency to find systemic solutions to tackle the root causes of poor air quality is clear. Doctors and other health professionals can lend their voices and credibility to broader environmental movements, including tackling short-lived climate pollutants which simultaneously contribute to poor air quality and climate change.

The good news is that California has already been a leader on climate policy, and maybe, the silver lining to the terrible tragedy of the 2018 fires is that empathy will grow among the public to demand stronger measures to protect our air not only here, but across the globe. [12] For those doctors, nurses, and health professionals who for the first time have needed to balance the health of their patients, their families, and themselves, let’s join the fight for a healthier environment for all.

Lily Morrison has a masters in public health, and currently works as a research data analyst at the University of California, San Francisco.

Amy Chen, graduated from Harvard Medical School and is currently a 2nd year dermatology resident at University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA

Amy Chen, graduated from Harvard Medical School and is currently a 2nd year dermatology resident at University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA

Natalia Linou has worked in international development and global health for over a decade and currently leads the environment and health portfolio at the United Nations Development Programme, New York.

Natalia Linou has worked in international development and global health for over a decade and currently leads the environment and health portfolio at the United Nations Development Programme, New York.

Eleni Linos is Associate Professor of Epidemiology and Dermatology at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF). She serves as the Director of the Program for Clinical Research and the Director of Diversity for the Department of Dermatology at UCSF

Eleni Linos is Associate Professor of Epidemiology and Dermatology at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF). She serves as the Director of the Program for Clinical Research and the Director of Diversity for the Department of Dermatology at UCSF

Competing interests: None declared

Resources:

- California wildfires: Nearly 1,000 unaccounted for in Camp Fire. CBS News. November 19, 2018.

- AirNow. Air Quality Index (AQI) Basics. 2016; https://airnow.gov/index.cfm?action=aqibasics.aqi. Accessed November 16, 2018.

- Dineen J, Wu G. Northern California air quality rated the worst in the world, conditions ‘hazardous’. San Francisco Chronicle. November 16, 2018.

- Liu JC, Pereira G, Uhl SA, Bravo MA, Bell ML. A systematic review of the physical health impacts from non-occupational exposure to wildfire smoke. Environmental Research. 2015;136:120-132.

- Youssouf H, Liousse C, Roblou L, et al. Non-accidental health impacts of wildfire smoke. Int J Environ Res Public Health.11(11):772-804.

- Kelly FJ, Fussell JC. Air pollution and public health: emerging hazards and improved understanding of risk. Environmental geochemistry and health. 2015;37(4):631-649.

- Wettstein ZS, Hoshiko S, Fahimi J, Harrison RJ, Cascio WE, Rappold AG. Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Emergency Department Visits Associated With Wildfire Smoke Exposure in California in 2015. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2018;7(8):e007492.

- WHO. Air Pollution. 2018; https://www.who.int/airpollution/en/.

- WHO. WHO Global Urban Ambient Air Pollution Database (update 2016). 2018; http://www.who.int/phe/health_topics/outdoorair/databases/cities/en/.

- Landrigan PJ, Fuller R, Acosta NJR, et al. The Lancet Commission on pollution and health. The Lancet. 2018;391(10119):462-512.

- Bell ML, Ebisu K. Environmental inequality in exposures to airborne particulate matter components in the United States. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2012;120(12):1699-1704.

- WHO. BreatheLife: A global campaign for clean air. 2018; http://breathelife2030.org/.