If nurses and doctors believe that the NHS will get worse after Brexit, they should spread this message—it could change minds, says Christina Pagel

For someone working in the NHS, it can feel as if all you can do is watch the disaster of Brexit unfold, and that none of it lies within your control.

For someone working in the NHS, it can feel as if all you can do is watch the disaster of Brexit unfold, and that none of it lies within your control.

But recent data from a large YouGov survey carried out on behalf of the People’s Vote Campaign suggests that your voice does matter.

The survey data suggest that people who are concerned about the impact of Brexit on the NHS are more likely to want to vote remain in any future referendum. At the same time, surveys show that doctors and nurses are trusted by the general public far more than any of the other voices currently speaking about Brexit. So the voices of doctors, nurses, and other health professionals do matter.

In early September 2018, the People’s Vote campaign ran a YouGov survey of over 8000 representative UK voters. The survey included questions about what impact people expected Brexit to have on the NHS and how they might vote in any new referendum on EU membership.

For each respondent, we also knew a range of demographic data including: age, gender, location, education level, employment status, 2016 referendum vote, 2017 general election vote, and National Readership Survey (NRS) social grade.

The results of the poll demonstrate that people who voted remain in the 2016 referendum largely believe the NHS will get worse after Brexit (65%), with very few believing it will improve (4%) (the remaining 31% either think the NHS will stay the same or don’t know). Among those who voted leave, 37% believe that the NHS will improve after Brexit and 12% believe it will get worse (51% think the NHS will stay the same or don’t know).

Those who did not vote in the referendum are more likely to say that they will vote for remain than leave (51% remain vs 28% leave). Given the close result in 2016, even small shifts could have a big impact, and a recent the Channel 4 / Survation poll indicates that opinion is continuing to shift towards remain—albeit slowly.

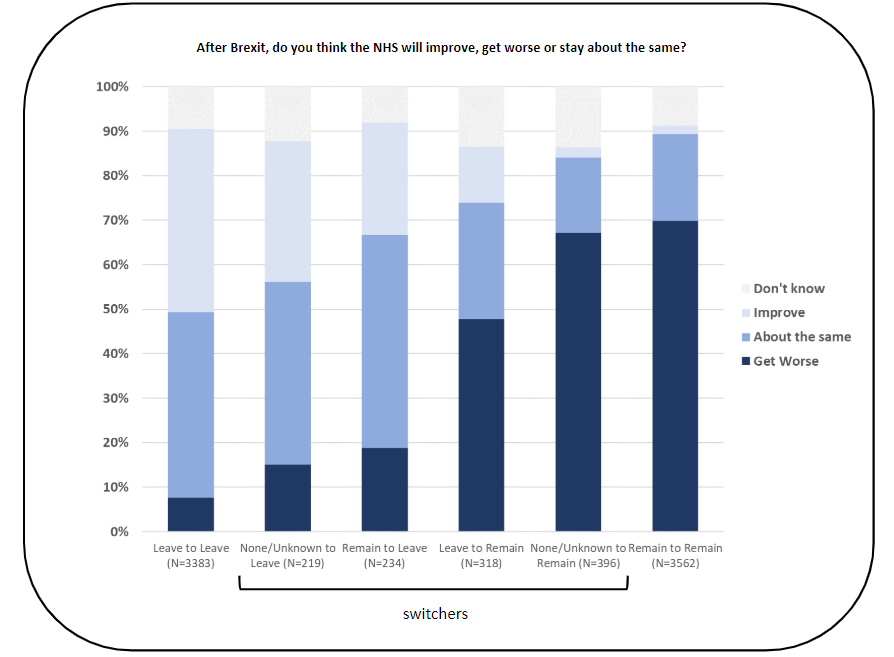

Among those who changed their view on Brexit since the 2016 referendum, there is a clear pattern (see Figure 1), although relatively few voters have changed their view (only 8% of leave voters say that they would vote remain in a new referendum and 6% of remain voters would vote leave).

Figure 1. Results to questions about the NHS after Brexit, broken down by referendum vote in 2016 and a putative people’s vote. Overall N=8112 (Don’t knows for a new referendum excluded).

Leavers who have switched to remain are more likely to believe that the NHS will get worse (48%) than leavers who are sticking with leave (8%). Similarly, remainers who have switched to leave are much less likely to believe that the NHS will get worse (19%) than remainers sticking to remain (70%). This pattern holds too for those who did not vote in 2016.

These data cannot distinguish between correlation and causation, and we know that there will be many confounding factors influencing how people would vote in a new referendum.

To account for potential confounding factors that were available from the survey data, I performed a multivariable regression on the data to estimate the adjusted risk ratios for the binary outcome of “would vote remain” vs “would vote leave” in a new referendum. I excluded the “don’t knows” and took into account all the demographic variables listed above.

In this multivariable model, believing that the NHS would get worse after Brexit was independently associated with a 60% increase in the likelihood of voting remain.

Unsurprisingly, how people voted in the 2016 referendum and in the 2017 general election were strongly associated with voting intention in any new referendum. Age was an important factor, with older voters less likely to vote for remain. And believing that the economy would get worse after Brexit was also strongly associated with an increased likelihood of voting remain in any new referendum. But gender, social grade, and region were not significantly associated with intention to vote for remain in any new referendum, once other factors were taken into account.

Most of these factors are fixed: no one can change how people voted in the past, nor their age, region, or other basic demographic factors. But people’s opinions on what will happen to the NHS or the economy after Brexit could change.

The multivariable regression indicated that the economy was a more important issue in influencing views on Brexit than the NHS, but is it the most useful? How would minds be changed on this issue? A 2017 Ipsos Mori survey showed little public trust in people who might convey a message about the impact of Brexit on economy: only 37% trusted business leaders, and less than 20% trusted politicians.

But 94% of the public trusted nurses and 91% trusted doctors to tell the truth. In fact, these are the two most trusted professions in the UK.

Although we cannot say that believing the NHS will get worse would lead to people voting for remain in any new referendum—especially as we cannot claim to have accounted for all confounders—the multivariable results are nonetheless suggestive.

If you believe that the NHS will get worse after Brexit and you spread that message among your friends, family, and colleagues, then perhaps you can change people’s minds on that.

At worst, you would be advocating for the NHS, and at best, you could help create new remain voters. Such advocacy represents a way that you too can take back some control in this time of confusion and division.

Christina Pagel is a professor of operational research at University College London. Twitter @chrischirp

Competing interests: Christina Pagel has been working with the People’s Vote Campaign in analysing their survey data in her spare time. She is volunteering her time and has not received any payment for the work.