As I mentioned last week, the Pharmacopoeia Londinensis, the Edinburgh Pharmacopoeia, and the Dublin Pharmacopoeia were eventually combined, in 1864, to form the British Pharmacopoeia (Pharmacopoeia Britannica), as recommended and announced in the Medical Acts of 1858 and 1862 respectively. It is still with us, published annually, under the aegis of the British Pharmacopoeia Commission and the Commission on Human Medicines.

As I mentioned last week, the Pharmacopoeia Londinensis, the Edinburgh Pharmacopoeia, and the Dublin Pharmacopoeia were eventually combined, in 1864, to form the British Pharmacopoeia (Pharmacopoeia Britannica), as recommended and announced in the Medical Acts of 1858 and 1862 respectively. It is still with us, published annually, under the aegis of the British Pharmacopoeia Commission and the Commission on Human Medicines.

The Medical Act 1858 gave the responsibility for producing the new pharmacopoeia to a Commission established by the General Council of Medical Education and Registration of the United Kingdom (now the General Medical Council), which the Act had also established.

The Medicines Act 1968 deals with the British Pharmacopoeia in Part VII, Sections 98–103. It says that “if by any instrument executed after the passing of this Act the General Medical Council assign [sic] to Her Majesty the copyright in the British Pharmacopoeia, in so far as that copyright is invested in the Council, then on the date on which that asisgnment is expressed to take effect … section 47 of the Medical Act 1956 (which relates to the publication of the British Pharmacopoeia under the direction of the Council) shall cease to have effect.”

In fact, the British Pharmacopoeia Commission was established soon afterwards, in 1970, as a Section 4 committee under the Medicines Act 1968, and it replaced the Commission that the General Medical Council had established. The British Pharmacopoeia Commission is responsible for preparing new editions of the British Pharmacopoeia and the British Pharmacopoeia (Veterinary), for keeping them up to date, and for selecting and devising British Approved Names (BANs) of medicines. For the most part, those names are the same as the International Nonproprietary Names (INNs) devised by the WHO.

The word “pharmacopoeia”, comes from the Greek word ϕαρμακοποιία, literally “drug-making”, which was found in the post-classical (Hellenistic) dialect called Koine. Instances in mediaeval Latin include the titles of books such as Pharmacopoeia seu de medicamentorum simplicium delectu: praeparationibus, mistionis modo by Jacques Dubois (Basel, 1552) and Pharmacopoeia, medicamentorum omnium, quae hodie ad publica medentium munia in officinis extant by Anutius Foesius (Basel, 1561).

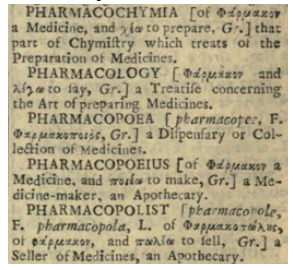

“Pharmacopoeia” entered English at the start of the 17th century. Coincidentally the first recorded instance is from 1618, the year in which the Pharmacopoeia Londinensis was first published, and is found in a reference to a “Pharmacopaea” by Querketanus in a translation by Thomas Bretnor of a Latin text by Angelus Sala Vincentinus Venitus (1576–1637) called Opiologia: or, A treatise concerning the nature, properties, true preparation and safe use and administration of opium. For the comfort and ease of all such persons as are inwardly afflicted with any extreame grief, or languishing pain, especially such as deprive the body of all natural rest, and can be cured by no other means or medicine whatsoever. A pharmacopoeia is “an authoritative or official treatise containing listings of approved drugs with their formulations, standards of purity and strength, and uses” (Oxford English Dictionary). In the early 18th century it also came to mean a dispensary or collection of medicines, as Nathan Bailey put it in his Universal Etymological English Dictionary of 1721 (Figure 1), but it is the earlier meaning that prevails today.

Figure 1. Words beginning with “pharmaco-” in Nathan Bailey’s dictionary

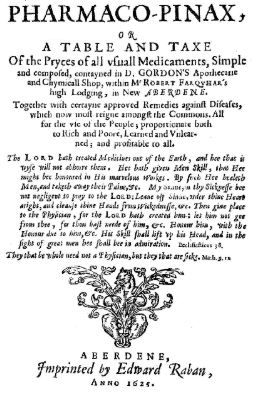

An earlier word still, “pharmacopinax”, came from the Greek word πίναξ, a board or plank, a platter, a public notice board, and a board or plate for painting, drawing, or printing on, a writing-tablet. In postclassical Latin it meant an astronomical table or a table for calculating the date of Easter. It also appeared in several Latin titles, such as Pinax iconicus antiquorum ac variorum in sepulturis rituum” by Lilius Gregorius Giraldus (Lyon, 1556), Pinax theatri botanici by Caspar Bauhin (Basel, 1623), and Pinax rerum naturalium Britannicarum, by Christopher Merrett (London, 1666). However, the only English pharmacopoeial instance of which I am aware is Pharmaco-Pinax, or a Table and Taxe of the Pryces of all vsuall Medicaments, Simple and composed, contained in D. Gordon’s Apothecarie and Chymicall Shop, published in Aberdeen in 1625 (Figure 2). A table of tablets, so to speak.

Figure 2. The title page of the Aberdeen Pharmaco-Pinax of 1625

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.