This year we celebrate not only the 50th anniversary of the Medicines Act 1968, aspects of which I have been discussing during the last few weeks, but also the 400th anniversary of the Pharmacopoeia Londinensis, published in 1618, and the 500th anniversary of the foundation in 1518 of the College of Physicians, as it then was, by Henry VIII. These events are linked.

This year we celebrate not only the 50th anniversary of the Medicines Act 1968, aspects of which I have been discussing during the last few weeks, but also the 400th anniversary of the Pharmacopoeia Londinensis, published in 1618, and the 500th anniversary of the foundation in 1518 of the College of Physicians, as it then was, by Henry VIII. These events are linked.

When the College was founded, medicines could be prescribed by apothecaries as well as by physicians. Apothecaries originally purveyed non-perishable commodities—spices, drugs, comfits, preserves, and the like. They were members of the Guild of Grocers, classed with pepperers and spicers, but they gradually focused on medicines, and by about the middle of the 14th century they were practitioners who prepared and sold drugs for medicinal purposes. However, in 1540 Henry VIII promulgated The Pharmacy Wares, Drugs, and Stuffs Act, empowering the physicians to inspect apothecaries’ wares and destroy them if defective.

Although the apothecaries were keen to be recognized as independent practitioners, their requests were refused until 1617, when The Worshipful Society of the Art and Mistery of Apothecaries was founded under James I. The title of the Society implied, perhaps, that a little hocus-pocus did not go amiss when your remedies had little or no efficacy.

The College of Physicians had first discussed publishing a pharmacopoeia in 1585, intending it to be adopted by all apothecaries, but the task was considered too burdensome. However, the idea was revived in 1589, when it was “proposed, considered, and resolved that one definitive public and uniform dispensatory or formulary of medical prescriptions, obligatory for apothecaries’ shops, should be prepared.” Preparation of the Pharmacopoeia began, but progress was slow; the project lapsed in 1594 and was not revived until June 1614.

The foundation of the Society of Apothecaries in December 1617 had been supported by two Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians, Dr Henry Atkins and Sir Théodore Turquet de Mayerne, both of whom had been working on the College’s pharmacopoeia. Since the pharmacopoeia had always been intended to be used by all apothecaries, the physicians then increased their efforts. The Pharmacopoeia Londinensis was published on 7 May 1618.

However, the physicians then claimed that the first edition had been botched at the printers’ shop. The College withdrew it and issued a greatly expanded revised version, which they designated the first edition, on 7 December 1618, claiming in an epilogue that the printer of the earlier version had “snatched away from our hands this little work not yet finished off, …defiled with so many faults and errors, incomplete and mutilated because of lost and cut off members”. Which is supposedly why the Pharmacopoeia Londinensis had two first editions. Whether this was the true reason is unclear and other explanations are possible.

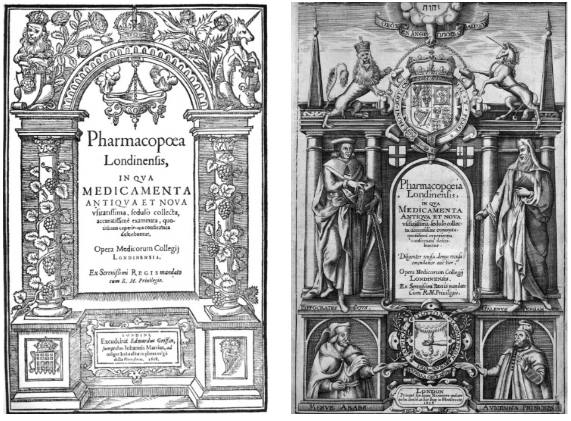

For example, Clare Fowler, in an excellent recent account of the history of the Pharmacopoeia Londinensis, has suggested that Mayerne prematurely submitted his own version to the printer, to the dissatisfaction of the other Fellows, who replaced it with the later version. Comparison of the title pages of the two versions (Figure 1) suggests another possible explanation. The physicians may not have liked the title page in the first version, which shows some of the royal symbols, such as the lion and the unicorn, but not the King’s or the College’s coat of arms. The King himself may have been displeased with the first version—his proclamation, that “all Apothecaries of this Realme [should] follow this Pharmacopoeia … upon paine of our high displeasure”, was inadvertently omitted from the early impressions. Another reason for blaming the printer, Edward Griffin.

Figure 1. The title pages of the two versions of the 1618 Pharmacopoeia Londinensis. Among the many differences, note the absence of the royal coat of arms and that of the College from the May 1618 version (left) and the difference in the spelling of the word “Pharmacopoe[i]a”

The Pharmacopoeia Londinensis laid the foundations for other national pharmacopoeias, the Edinburgh Pharmacopoeia (1699) and the Dublin Pharmacopoeia (1807). The last edition of the London Pharmacopoeia, the 11th, appeared in 1851. By then the need for harmonization had become clear, particularly since the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, with the institution of infirmaries and dispensaries, had resulted in increasing demands for medicines. The British Pharmacopoeia (Pharmacopoeia Britannica), recommended and announced in the Medical Acts of 1858 and 1862 respectively, appeared in 1864 and is still in use today. It was mentioned in the Medicines Act 1968, as I shall discuss next week.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.