One standardised solution to antimicrobial resistance will not be appropriate across all settings, say Mishal S Khan and colleagues

The global crisis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is largely a result of extensive antimicrobial drug misuse. Consequently, global health policy makers at the highest levels have called for countries to combat AMR by reducing the inappropriate use of antibiotics,[1][2][3] with the suggestion that one way to do this is by making antibiotics accessible only with a prescription. On the surface, prescription only access to antibiotics—a policy which is common in high income countries but rare in low and middle income countries (LMICs)—seems a reasonable approach to combat AMR. However, we’d argue that this approach is both infeasible and inequitable in many LMIC settings.

This proposal fails to consider geographical differences in the distribution of licensed providers and how this may affect population health—a common oversight in discussions about policies to combat AMR. Yet our ongoing research in Cambodia offers insights into how the distribution of licensed providers could hinder a prescription only policy and patients’ access to antibiotics.

In Cambodia, only pharmacies and outlets that are registered with the Ministry of Health can legally sell antibiotics in the private or public sector. The Department of Drugs and Food is the government authority responsible for the regulation of the pharmaceutical sector, and a list of registered pharmacies is published online regularly. At present, however, informal drug sellers greatly outnumber registered pharmacies, and, despite the law, it’s been been found that most medications are purchased from these informal drug sellers rather than registered pharmacies.[4][5]

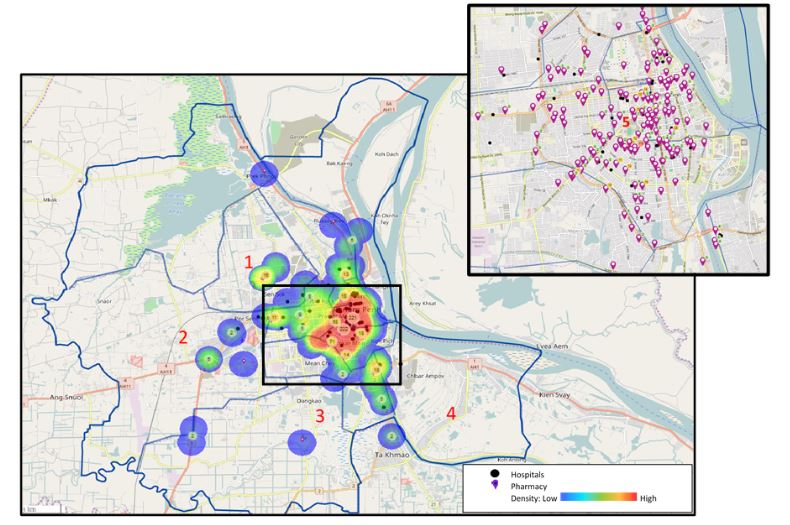

Our work mapping all the registered pharmacies and hospitals [figure 1] across the 12 districts of Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital and most populous city, reveals stark geographical inequalities in the distribution of pharmacies. The peripheral districts have a much lower density of registered pharmacies and hospitals compared with the central districts. For example, only seven registered pharmacies are located in the Por Senchey district despite this area having a population of approximately 185 000 people; each pharmacy in Por Senchey must serve approximately 26 000 people and cover 23 square kilometres—an area that is almost double the size of Geneva, Switzerland. In contrast, the centrally located district of Prampir Meakkakra has 18 registered pharmacies, with one pharmacy every 0.1 square kilometres.

This geographical inequality means that if informal drug sellers are prevented from selling antibiotics, communities that are underserved by formal healthcare providers may be left without adequate physical access to antibiotics. While such policies may reduce the inappropriate use of antibiotics, they could also disproportionately reduce access in areas that may have the highest unmet need for antibiotics. This geographical inequality is not unique to Phnom Penh or Cambodia either. Inequalities in people’s physical access to formal healthcare providers is common in other Asian LMICs and exists in the majority of LMICs.[6][7]

Although antibiotic overuse is a pressing health challenge, we can’t forget that many communities still lack access to essential medicines and to trained, legally registered healthcare providers. The proliferation of, and demand for, informal providers must be understood within the broader social, economic, and geographical realities of LMICs. Any efforts we make to restrict access to antibiotics—either through enforcing existing rules or introducing new ones—must take into account the geographical inequalities that exist in the distribution of licensed healthcare providers.

While little research has been carried out into the effectiveness of policies to combat AMR in LMICs, it is clear that one standardised solution, such as requiring a prescription for antibiotics, will not be appropriate across all settings. The supply and demand for antibiotics in the human health sector is characterised by the interconnectedness of several stakeholders, and many of them believe that liberal use of antibiotics is beneficial to them or their businesses. Global strategies that call for antibiotic access to be prescription only largely ignore the complexity of tackling antibiotic misuse, and the need for local ownership in order for sustainability. Such policies would likely be met with a number of barriers to long term implementation and could unintentionally exacerbate health inequalities.

Mishal S Khan, assistant professor of health policy and systems research, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, and One Health technical adviser, Chatham House Centre on Global Health Security. You can find her on Twitter @DrMishalK

Sonia Rego, research assistant, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

Julia Spencer, research assistant, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. You can find her on Twitter @JuliaHSpencer

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: None.

Acknowledgements: MSK and SR are conducting research on unregistered drug sellers in Cambodia and receive funding from the UK Research Council’s Health System Research Initiative.

References

[1] Group of 20. Berlin Declaration of the G20 Health Ministers. Berlin; 2017. Available from: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/fileadmin/Dateien/3_Downloads/G/G20-Gesundheitsministertreffen/G20_Health_Ministers_Declaration_engl.pdf

[2] United Nations (UN). High-level Meeting on Antimicrobial Resistance [Internet]. New York: United Nations; 2016. Available from: http://www.un.org/pga/71/event-latest/high-level-meeting-on-antimicrobial-resistance/

[3] Om C, Daily F, Vlieghe E, McLaughlin JC, McLaws ML. Pervasive antibiotic misuse in the Cambodian community: Antibiotic-seeking behaviour with unrestricted access. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2017;6(1):30.

[4] Khan MH, Okumura J, Sovannarith T, Nivanna N, Nagai H, Taga M, et al. Counterfeit medicines in Cambodia—possible causes. Pharm Res 2011;28(3):484–9.

[5] Yang D, Plianbangchang P, Visavarungroj N, Rujivipat S. Quality of pharmaceutical items available from drugstores in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2004;35(3):741–7.

[6] Khan M S, Ning Y, Jinou C, et al. Are global tuberculosis control targets overlooking an essential indicator? Prolonged delays to diagnosis despite high case detection rates in Yunnan, China. Health Policy and Planning 2017;32: i15-i21. https://academic.oup.com/heapol/article/32/suppl_2/ii15/4430541

[7] Say L, Raine R. A systematic review of inequalities in the use of maternal health care in developing countries: examining the scale of the problem and the importance of context. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2007;85: 812-819. http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/85/10/06-035659-table-T1.html