From the earliest times religion has influenced medicine and vice versa. For example, if obeying a religious law compromises one’s health, the law may sometimes be broken. Jewish law dictates that anyone who is seriously ill, or may become seriously ill by fasting, is not allowed to fast on Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement; evidence that fasting for 25 hours on Yom Kippur independently increases the risk of a preterm delivery suggests that this prohibition on fasting should be extended to pregnant women, at least in their final trimester.

From the earliest times religion has influenced medicine and vice versa. For example, if obeying a religious law compromises one’s health, the law may sometimes be broken. Jewish law dictates that anyone who is seriously ill, or may become seriously ill by fasting, is not allowed to fast on Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement; evidence that fasting for 25 hours on Yom Kippur independently increases the risk of a preterm delivery suggests that this prohibition on fasting should be extended to pregnant women, at least in their final trimester.

Gods and saints have also often been invoked for medical reasons. For example, in his autopathography The Sacred Orations (AD 170/171), Aelius Aristides gave an account of his ill health, praising the Greek God of medicine, Apollo, and criticizing his physicians.

Last week I discussed St Vitus and his dance. Many other religious figures associated with illnesses are listed in a Wikipedia page titled “Patron saints of ailments, illness, and dangers”. Here is a selection of patron saints of particular medical specialties.

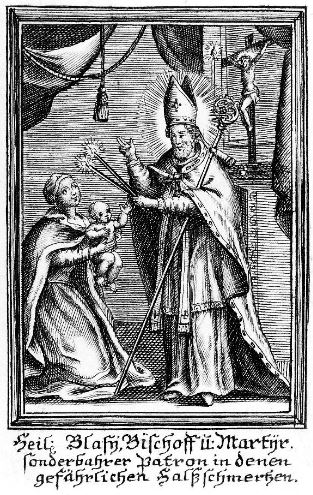

Saint Blaise or Blasius, who was martyred in 316 AD by Agricola, the governor of Cappadocia, for failing to renounce his Christian faith during the reign of Diocletian, started his career in Armenia as a general practitioner. He specialized in treating diseases of the throat, coughs, quinsy, goitre, whooping-cough, and children’s diseases. Agricola had him scourged and thrown into prison. He was then tied to a stake and his flesh was torn with nails and iron combs. After being imprisoned again, he was thrown into a deep lake, with a large stone tied round his neck. When he rose to the surface and walked on the waters he was beheaded. As he died he prayed that he might be allowed to help all those with diseases of the throat. He is therefore the patron saint of laryngology. His Saint’s Day is 3 February.

Saint Blaise, by prayer miraculously curing a child of a fish bone in the throat (a spiritual Heimlich manoeuvre?); the legend reads “Heil. Blasii, Bischoff u[nd] Martyr, sonderbahrer Patron in denen gefährlichen Halssschmerzen.” (“Hail, Blaise, bishop and martyr, special patron of those with serious pain in the throat”); from a prayer leaflet, 304 AD (Wellcome Images CC BY 4.0)

The patron saint of ophthalmology is Saint Lucy, of whom various stories are told. In one version she found when she was 13 that when she looked at a man her mind became filled with sinful thoughts, and the more she looked, the more she sinned. She therefore plucked out her own eyes. In another version she wanted to discourage a persistent suitor who admired her eyes. In a third version, her eyes were gouged out during her martyrdom by Paschasius, the governor of Syracuse, during the reign of Diocletian. In all versions her eyes were restored by divine intervention. It may not be entirely coincidental that her name comes from the Latin word for light, lux. Her Saint’s Day is 13 December, commemorated in a poem by John Donne, A Nocturnal upon St. Lucy’s Day, being the shortest day (1627).

In this 15th century painting by Francesco del Cossa (ca 1430–ca 1477), Saint Lucy is seen holding her original pair of eyes in her left hand.

René Goupil (1608–42) was a French surgeon and lay missionary who worked in the Hôtel Dieu de Québec. While on a mission to Huron territory, he and his group were captured by Canadian Indians and tortured. However, he gave them medical assistance when they needed it, concerned as he was to alleviate pain and suffering. He was canonized in 1930 and was made the patron saint of anaesthesia in 1951. His Saint’s Day in Canada is 29 September.

Who should be the patron saint of pharmacology and clinical pharmacology? Drug actions are mediated by chemical signalling, and chemical recognition is the function of receptors, which are major targets of many important medicines. The mechanism whereby drug–receptor interactions are translated into therapeutic outcomes involves chemical transmission by substances generally known as second messengers. So, no saint is better qualified to be the patron saint of pharmacology than God’s great messenger himself, the archangel Gabriel.

The Annunciation (1501) by Pinturicchio. Gabriel’s feast day was originally celebrated on 18 March, but since 1969 the Church of England has celebrated it on 29 September

In his capacity as a messenger Gabriel appears to the prophet Daniel, explaining his visions (Daniel 8:16 and 9:21), to Zacharias and his wife, foretelling the birth of John the Baptist (Luke 1:11), and to the Virgin Mary, foretelling the birth of Jesus (Luke 1:26).

In Hebrew, Gabriel’s name, גבריאל, means God is my strength, which is also highly appropriate for pharmacology, reminding us of the centrality of the dose-response curve to pharmacological actions: the more of a medicine you give, the bigger the effect.

So we should celebrate Pharmacology Day on Saint Gabriel’s Day, 29 September. It will be followed this year by Clinical Pharmacology Month, October, with a range of activities, including case presentations at grand rounds and prize competitions for medical students.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.