There is currently a lot of talk about tit for tat, whether in the spheres of diplomacy or trade.

There is currently a lot of talk about tit for tat, whether in the spheres of diplomacy or trade.

Of course, when medical readers see the term “tit for tat”, they will immediately think of the type VI secretion system that bacteria use to target other cells by translocating effector proteins. Or perhaps the substitution of inosine for adenine in a TAT sequence of bases in DNA, giving TIT instead of TAT. Or perhaps not.

The noun phrase “tit for tat” may have arisen as a variant of “tip for tap”, one stroke in return for another. The former, the earliest citation of which in the Oxford English Dictionary is from 1546, appears to antedate the latter by about 30 years, although that is a short enough time for the possibility of an antedating of the former by the latter. Another possible origin is from the Dutch dit vor dat, this for that. However, collateral evidence for the other hypothesis comes from Shakespeare’s use of “tap for tap” in Henry IV Part 2 (2.i.195) in the context of a fencing bout. This idea goes back to the biblical principle of an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, and the Roman lex talionis, in English talion law, retaliation, or, in the words of the Mikado in Gilbert and Sullivan’s opera of that name, letting the punishment fit the crime.

Originally the phrase was used literally, but before long metaphorical usages emerged, as in the old Scottish proverb that demeans the efforts of women in the face of insuperable odds, given, for example, in the form of a Wellerism in James Kelly’s A Complete Collection of Scottish Proverbs (1721): “Titt for tatt, quoth the Wife when she farted at the Thunder.”

Why do we say “tit for tat” and not “tat for tit”? The Dutch explanation of the origin of the phrase would answer this satisfactorily, but there is a deeper reason.

In English there is a fixed word order for adjectives, sometimes called the Royal Order, as follows: [determiner]-quality or opinion-size-age-shape-colour-place of origin or position-material-qualifier-[noun]. The initial determiner can be the definite or indefinite article (the or a[n]), a number or quantity (three, four, several, some), or a pronoun (his, her, that); the quality or opinion is a value judgment—good/bad, beautiful/ugly, interesting/boring; size, age, shape, colour, place of origin, and material need no explanation; the final qualifier is any adjective not covered by the other categories, for example, a purpose (a diagnostic test), a constituent (a barium meal), or a technique (an MRI scan). So, we say an indwelling, latex, urinary catheter (determiner, position, material, purpose) rather than any other order of the adjectives.

“Big bad wolf” is an exception to this. We should say “bad big wolf”, but we don’t because of a stronger rule—the preference for a particular order of vowels in consecutive words: e, then i, then a, then o, then u. For example, the giant in the story of Jack and the beanstalk says fee-fi-fo-fum. Here are examples of the variant called reduplication with vowel variation.

-

clip clop, criss cross, flip flop, hip hop, hippity hoppity, King Kong, singsong, tick tock, and tip top, not top tip (unless we’re giving one); and Mary Poppins always said “spit spot”, not “spot spit”.

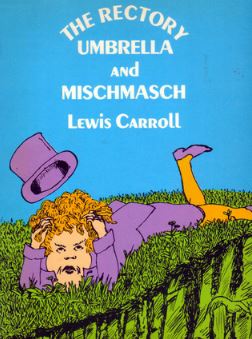

clip clop, criss cross, flip flop, hip hop, hippity hoppity, King Kong, singsong, tick tock, and tip top, not top tip (unless we’re giving one); and Mary Poppins always said “spit spot”, not “spot spit”. - chit chat, dilly dally, fiddle faddle, flim flam, jibber jabber, jingle jangle, knick knack, mish mash, pitter patter, shilly shally, splish splash, riff raff, wishy washy, and zigzag. “Jabberwocky” first appeared in an early version in Lewis Carroll’s magazine Mischmasch.

- bing bang bong, tic-tac-toe, and the Tritsch Tratsch Polka; the bells in Frère Jacques go “ding, dang, dong” and the ministers in Puccini’s opera Turandot are Ping, Pang, and Pong.

We see the same vowel order in the paradigms (present tense, past tense, and past participle) of some English verbs—sing, sang, sung and swim, swam, swum. This variation in vowels arises from a linguistic principle known as ablaut, a German term that was introduced by the 19th century philologist Jakob Grimm and which means an off sound or graduated sound. Richie Benaud’s advice to reduce the chance of skin cancer was “Slip, slap, slop” (slip on a shirt, slap on a hat, and slop on some sunscreen), which also demonstrates ablaut reduplication (slip/shirt, slap/hat). Spike Milligan illustrated the principle, but also comically subverted it, in his poem “On the Ning Nang Nong”.

On the Ning Nang Nong

Where the Cows go Bong!

and the monkeys all say BOO!

There’s a Nong Nang Ning

Where the trees go Ping!

And the tea pots jibber jabber joo.

On the Nong Ning Nang

All the mice go Clang

And you just can’t catch ’em when they do!

So its Ning Nang Nong

Cows go Bong!

Nong Nang Ning

Trees go ping

Nong Ning Nang

The mice go Clang

What a noisy place to belong

is the Ning Nang Ning Nang Nong!!

And that is why we say “tit for tat”, not “tat for tit”.

Next week I shall discuss whether the strategy of tit for tat is a beneficial one.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.