Urbanisation, said Jo Ivey Boufford, president of the International Society for Urban Health, at a C3 breakfast seminar last week, is one of the four great challenges to health along with climate change, aging of the population, and the epidemiological shift from infectious disease to non-communicable disease. But, she continued, thinking about urban health challenges some deep-seated attitudes, not least that “health equals medicine.”

Urbanisation, said Jo Ivey Boufford, president of the International Society for Urban Health, at a C3 breakfast seminar last week, is one of the four great challenges to health along with climate change, aging of the population, and the epidemiological shift from infectious disease to non-communicable disease. But, she continued, thinking about urban health challenges some deep-seated attitudes, not least that “health equals medicine.”

Thinking about health in terms of cities makes sense because more than half the world’s population now lives in cities and it’s expected to be 70% by 2050. The fastest growth will be not in megacities, but in cities of 250 000 to 500 000. A challenge to urban planners is how much to concentrate on megacities like Dhaka, Nairobi, and Lagos with huge slums and how much on preventing such slums in smaller cities.

Although they are half the world’s population, cities are 70% of the global economy and account for 70% of greenhouse gas emissions and 70% of waste.

Another reason for paying close attention to cities is that cities and city leaders can often do things that governments can’t. Boufford comes from New York, and the US is a good example with many cities saying that they will comply with the Paris agreement on climate change when the Federal government has withdrawn. There are several global networks of cities.

Those who think about urban health have conceptualised it in four ways: density, diversity, complexity, and inequality. Density can be good, but clearly the density of slums is bad for health. Diversity can make cities “rich and exciting,” but can also make it difficult to deliver services. Queen’s in New York, for example, has 2.2 million people speaking 138 different languages. Boufford showed the extraordinarily complex organogram of New York and said how the City’s administrations spend is divided into “stove pipes” that struggle to work together. Inequalities are stark in cities, and Boufford, who used to be president of the New York Academy of Medicine, said how she could see from her office both the poverty of Harlem and the great wealth of the Upper East Side.

Boufford warned against a common tendency to think that cities are inevitably bad for health. They are neither automatically good or bad, and, she said, “governance is the key”: whether the people are involved in planning; voice and accountability; security; government effectiveness; regulation; the rule of law; and control of corruption.

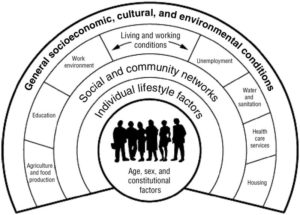

Showing the Dahlgren-Whitehead rainbow of deteminants of health (see figure). Boufford said how 75% of health depends on where you live. Health care accounts for only a small amount, perhaps 10%, of health.

But there are, said Boufford, three big challenges to thinking about urban health. Firstly, for most people, including politicians, “health equals medicine.” Secondly, the international development agencies are focused on rural areas. Thirdly, when international agencies do invest in health the investment is disease oriented.

The medical model of improving global health concentrates on health systems, the health workforce, and essential medicines, whereas the “health for all” model concentrates on urban planning, transportation, housing, and socioeconomic factors.

Boufford, hitting her forehead with her palm said that she long ago decided that “You are never going to get the money out of health systems.” But there are huge sums of money in enterprises like transport systems and housing. Yet the people who run those systems don’t think that health is anything to do with them. The trick for those interested in urban health is to work with those people to do what they are going to do anyway but help them to factor in health. Boufford had success with this approach in New York.

And those investments can make a huge difference. Boufford told the story of Bogota where investment in transport was concentrated on a pro-poor public transport system versus Karachi where investment was spent on ring roads and flyovers.

The Sustainable Development Goals include both health (Goal 3) and sustainable cities (Goal 11), but the health goal, with its emphasis on universal health coverage and disease, is dominated by the medical model, while the cities’ goal belongs to urban planners and doesn’t mention health. Nevertheless, those interested to improve urban health are likely to achieve more through Goal 11 than Goal 3.

And the community interested in urban health is growing, and both China and India now have plans for healthy cities. There should soon be some for Africa, and the next International Conference on Urban Health will be held in Kampala in November. The topics include not only those that would be expected, but “spiritual health in the city,” which is not so much about faith, but about how can people living in the most desperate circumstances find meaning in their lives. (I think of the diagnosis of Harry Burns, former chief medical officer in Scotland, that the health of Glaswegians deteriorated when the shipyards closed and people struggled to find meaning in their lives.)

A dramatic and in some ways amusing incident came in the discussion after Boufford’s talk when Dame Parveen Kumar, a professor of medicine and co-editor of one of the best known textbooks of medicine, said “You make me think that I have wasted 40 years of life.”

Richard Smith was the editor of The BMJ until 2004.

Competing interest: RS was an unpaid board member of C3.