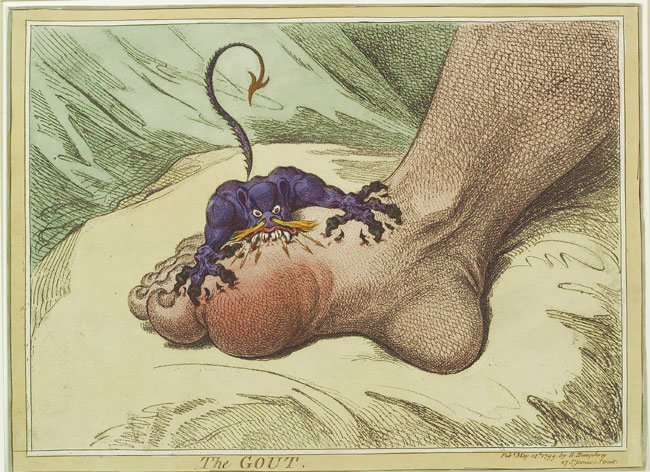

Richard Asher once commented, citing Pel Ebstein fever in Hodgkin’s disease as an example, that some clinical manifestations that are regarded as “typical” of certain diseases may be in fact rather uncommon or even non-existent. It is several years since I last saw a patient with gout that presented as podagra, affecting the big toe. “It’s gout, isn’t it, doctor?” He had probably seen cartoons of army colonels with their feet swathed in bandages, or perhaps James Gilray’s famous depiction of the gout demon (picture). I confirmed the diagnosis. “What is it exactly?” he asked.

Richard Asher once commented, citing Pel Ebstein fever in Hodgkin’s disease as an example, that some clinical manifestations that are regarded as “typical” of certain diseases may be in fact rather uncommon or even non-existent. It is several years since I last saw a patient with gout that presented as podagra, affecting the big toe. “It’s gout, isn’t it, doctor?” He had probably seen cartoons of army colonels with their feet swathed in bandages, or perhaps James Gilray’s famous depiction of the gout demon (picture). I confirmed the diagnosis. “What is it exactly?” he asked.

The IndoEuropean root GHEU meant to pour or gush, like a geyser, or like digestive products pouring through the gut. In Latin guttur was the throat, the passageway down which things are poured, near which you may develop a goitre, and a gutter is something into which things are poured and along which they flow. Gout comes from the Latin gutta, a drop. “And on thy blade, and dudgeon, gouts of blood, which was not so before” Macbeth tells the visionary dagger that plagues him.

Gout was supposedly due to a “defluxion”, literally a flowing down, of certain humours in the body, whereby the drops of some noxious substance were deposited in the affected tissues. The falling gout (gutta cadiva in mediaeval Latin) was another name for epilepsy and Covent Garden gout and the ethnophaulism Spanish gout were both euphemisms for syphilis.

In his Herball of 1597, Gerard listed “Herba Gerardi, [which] is called in English Herbe Gerard, Aishweed, and Goutwoort, common names for the plant Aegopodium podagraria.” In his British Plants (1776) William Withering called it goutweed. It was supposedly so efficacious that even carrying it about with you would reduce gouty pains. The Latin name of the genus gives a hint about the possible origin of this supposition. Aegopodium comes from the Greek words αἴξ (genitive αἰγος), a goat, and πούς (genitive ποδος), a foot, and it was so called because its leaves bore a fanciful resemblance to the foot of a goat. So plants in the genus are really goatweeds rather than goutweeds. After it had been used for treating gout, Aegopodium podagraria was given its name from the Greek word ποδάγρα (from πούς and ἄγρα, a way of catching), which originally meant a trap for the feet.

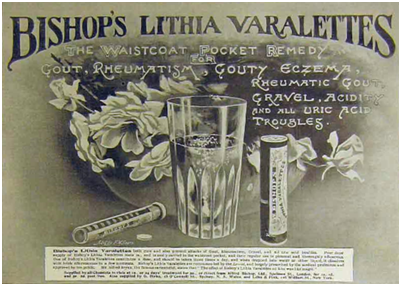

In an article published in the Daily Telegraph 100 years ago, on 27 February 1917, titled “The uric acid question” the anonymous author described the features of the disease and then claimed that Bishop’s Varalettes were the best treatment, ending with the news that a free booklet on the subject was available from its manufacturers, Alfred Bishop Ltd, at 48 Spelman Street, London NE. The article was in fact a disguised advert for the formulation, which was marketed as tablets (picture) and as a liquid in attractive blue glass bottles.

In another article in The Graphic in 1907, readers were told, under the headline “Bishop’s Varalettes are what you want”, that the medication was useful for acidity, heartburn, or flatulence, and stiff swollen or inflamed joints, and that it would provide “complete immunity from gout, rheumatism, rheumatic gout, gouty eczema, gouty indigestion, sciatica, lumbago, and kidney troubles.” A box containing enough treatment for 25 days cost 5 shillings (about £20 at today’s prices) and the treatment was available not only “from all chemists and drug stores” in the UK, but also “from the leading chemists in any country” and from “depôts” in Paris, Barcelona, Sydney, New York, Cape Town, and Johannesburg.

The Daily Telegraph told readers that “Bishop’s Varalettes are purely chemical in their action, and do not contain any of the dangerous medicinal drugs such as colchicum and its derivatives, the salicylates, iodides, mercury, potash, narcotics, and purgatives, which are such preponderating ingredients of other gout remedies.” However, in the BMA publication Secret Remedies (1909), Bishop’s Gout Varalettes were described as containing “lithium citrate and a small quantity of what appeared to be piperazine, together with the usual effervescing basis consisting of sodium bicarbonate and tartaric acid.” Presumably lithium citrate acted by being converted to the highly soluble salt lithium urate. I imagine that the use of this remedy, if effective, led to not a few cases of acute lithium toxicity.

I don’t know the origin of “varalette”. It does not seem helpful to know that “vara” in Latin denoted a branched structure and that “varal” means a clothesline in both Spanish and Portuguese.

I didn’t give my patient all these details, but explained that he had a kind of inflammation in the joint and described the treatment. He thought about it for a moment. “You mean, like it’s inflammable and caught fire?” “Sort of.” “But I haven’t put it anywhere near a fire.”

Acknowledgement: Thanks to Desmond Devitt for drawing my attention to the 1917 article in the Daily Telegraph.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.