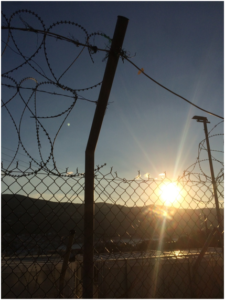

Our team arrives on mass to the camp, greeted by cold steel fences criss-crossing up two metres high and crowned by coils of sharp barbs. This is juxtaposed by colourful paintings on concrete walls.

Our team arrives on mass to the camp, greeted by cold steel fences criss-crossing up two metres high and crowned by coils of sharp barbs. This is juxtaposed by colourful paintings on concrete walls.

The next assault to our senses is “hallo,” “hallo,” “my friend,” “how are you,” and hugs and kisses from 10 or so scruffy weather-beaten children, who know our schedule and build greeting us into their bland and boring days. I have witnessed the progression of some of these children’s English just from the few weeks I have been here, and I wonder what they could achieve if they had lessons and a chance at an education.

Depending on where we leave our vehicles, which depends on what new restrictions are imposed on us by Greece’s First Reception Service/Reception and Identification Service (RIS), some days we trudge up through the camp’s steep concrete track, exchanging greetings with those we have come to know and call our friends, sweet blue eyed Syrian girls holding my hands and helping with bags and boxes filled with medical supplies and nappies.

After signing in, donning passes and our Boat Refugee Foundation (BRF) emblazoned vests, we set up in our medical cabin. Owing to severely limited space, both for new arrivals and organisations, every day we move the 20 or so boxes that make up the “milk room” into another space offered to us by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). By the time we are ready to start seeing patients, a queue has formed outside the door and we dive into the chaos.

Fifty patients and five hours later, we are knackered. Our nine square metre space is usually always full; families needing lice treatment; sick babies with diarrhoea, vomiting and accompanied by their concerned mothers; insomniacs unable to process the trauma of their journey over here. The other members of the team staff the “milk room,” where infant formula, porridge, juice, and hygiene products are given out, following the World Health Organization’s infant and young child feeding guidelines and with a strict monitoring system in place. They also provide chai—a warm cup of comfort to many on a cold evening. Children’s activities are also planned to give parents a break and to try to simulate some kind of normality.

This is a normal day.

There have been a few abnormal days recently though. We provided double medical shifts due to strikes from the Greek organisation providing medical care. Although I sympathise for the workers, the amount of work the organisation has taken on means it has a huge impact on medical care within the camp and the strike left the camp in a crisis situation. A few months ago, it was looking likely that there was no longer a role for the BRF because of this group, but when they went on strike we found ourselves the sole provider of medical services. I can’t help but feel horror at the thought of what the situation would be like if we had not been there. We act as a supplementary medical service, but it is clear that our presence is vital.

Another abnormal day was the onset of rain last month. A thunderstorm towards the end of our shift resulted in tensions rising and frustrations coming to a head with a riot breaking out, forcing us to evacuate. In reality, this meant clambering through a hole in the fence behind the cabin in torrential rain with the light from our head torches and phones, before realising our escape route was leading to the centre of the riot, so turning around and seeking shelter back in the camp in the police compartment. Unfortunately, this outbreak was started by a small number of individuals, but their subsequent march into town left destruction in their wake and gives the whole population of the camp a bad name on the island.

While waiting for the situation to calm down inside the police area, a particularly heart wrenching moment was witnessing the desperation of a man with a young family and baby whose tent had been completely washed away by the rain. Watching him across a wire fence despairing at his situation and angry at the whole world, while being unable to help him, was very distressing. Thankfully, the tension soon dispersed and volunteers rallied around to provide emergency shelter and blankets to those who needed it the most.

Some cases I have seen here have stuck inside my head. The trauma of a lady who’d just arrived on the island from Turkey, and who had witnessed the death of two young men who tried to swim to shore after 12 hours of being on a small boat. A family involved in a bomb blast a year ago. The youngest child unsteady on their feet, unable to hear properly, and struggling to interact properly with other children. The father left with chronic intractable pain from a bullet injury.

We also see numerous young men with psychological problems, who are anxious and distressed, but unable to find relief from their thoughts. I’ve seen many cases of self-harm and patients who are addicted to drugs from Turkey—an issue that we see a lot of the back end of.

Nearly 50% of the camp is composed of women and children. They do not walk around the camp past 10pm as “there are bad people.” Our translators warn us of troublemakers. Certain groups are used by the army for crowd control as they do not have enough staff. People complain to us that the control of the food line means certain groups get more supplies.

The town is also turning more dangerous. Despite Samos being a liberal island, there are anti-refugee marches, and businesses and empty hotels will not house vulnerable groups or rent space for use by refugees. I went to treat a young man, persecuted for being a Christian in Pakistan, attacked in prison on Samos for being a Christian by other refugees, and now beaten up by a group of young Greek men who followed him back from town, convinced he was Muslim.

The situation seems to be reaching boiling point as locals in Samos want a solution. Some propose a curfew to be imposed on the camp at night, with a signing in and out process. This is something my organisation cannot endorse, as it poses a very real safety risk for the refugees in case a mass evacuation is necessary. The situation here is not ideal for anyone. The EU-Turkey deal has complicated the registration process, so people cannot be easily moved onwards from the island to mainland Greece. This has meant the camp has changed from being a through route into a more permanent residence—something it does not have the facilities or mandate to be.

With the population of the camp three times larger than the area was designed for, worries about sewage, landslides, and asbestos exposure become topics of conversation in medical meetings—situations that will deteriorate with worsening weather. This has also changed the nature of the services required by camp residents—structured education is a vital requirement lacking in the camp, and medical needs such as monitoring of infant and child growth, breastfeeding services, antenatal care, and management of chronic conditions require more focus now. Again, this is not what the camp was designed for.

The stories are a mix of happy and sad and that is the nature of the camp. Sometimes it is necessary to stand back and see it all again for the first time. Whole families sleeping for weeks and months in a three person tent on a steep hill on the concrete ground, while the wind howls at night around the island.

One constant here is the ability of the situation to change. Let’s hope the tremors we have experienced so far do not ripple into an earthquake of greater magnitude.

Vanessa Yarwood is a junior doctor taking time out after foundation training to pursue her interest in global and refugee health. She worked in a refugee camp on the island of Samos, Greece, as a volunteer doctor for the Boat Refugee Foundation.

Competing interests: I have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: I worked as a volunteer doctor for the Boat Refugee Foundation on Samos from October to December 2016.